| Above: Saharan Air Layer analysis for 8 am EDT August 12, 2019. The orange colors show dry air from Africa’s Sahara Desert covering large portions of the tropical Atlantic, including most of the Caribbean Sea. Image credit: University of Wisconsin CIMSS. |

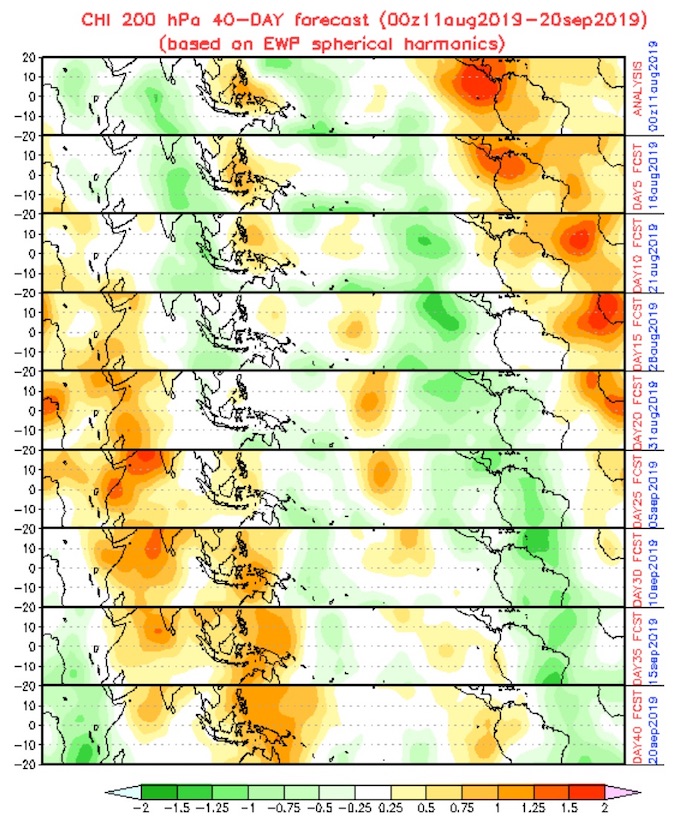

With the peak portion of the Atlantic hurricane season nearly upon us, the Atlantic is quiet this week, thanks to a large amount of dry, stable air. The dry air is largely due to the Saharan Air Layer, which has spread westwards from the Sahara Desert across most of the tropical Atlantic. In addition, the large-scale atmospheric circulation currently favors sinking motion over the region; sinking air warms and dries as it descends, creating dry, stable air that suppresses hurricanes (see Figure 5 below).

|

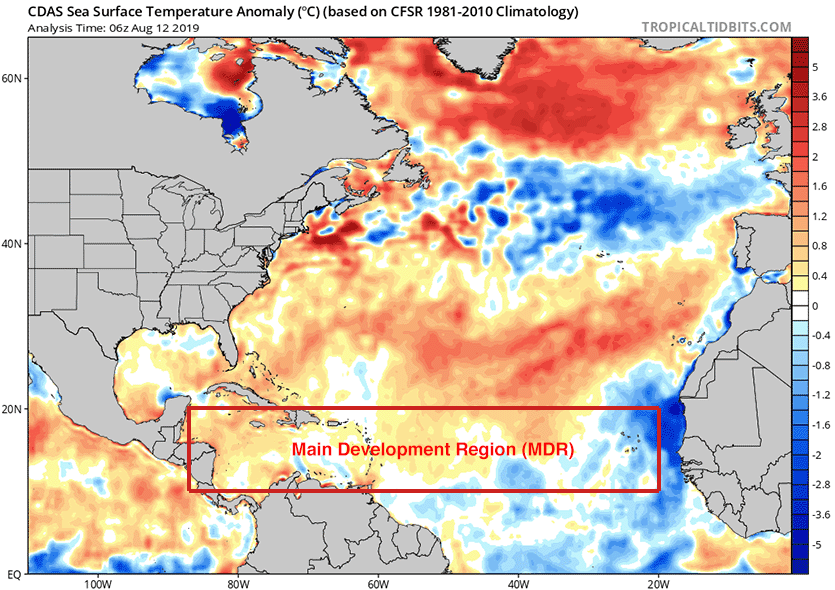

| Figure 1. Departure of sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Atlantic of August 12, 2019. SSTs in the Main Development Region (MDR) for hurricanes, from the coast of Africa to the coast of Central America, were slightly above average. Image credit: Levi Cowan, tropicaltidbits.com. |

Atlantic SSTs are favorable for development

We are nearing the seasonal peak in sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Northern Hemisphere, and ocean temperatures all across the tropical and subtropical Atlantic are above the 26.5°C (80°F) threshold typically needed to sustain a hurricane. Ocean temperatures will continue to warm until the first week of September, when SSTs typically peak for the year. SSTs in the Main Development Region (MDR) for hurricanes, from the coast of Africa to the coast of Central America, are currently about 0.2°C (0.36°F) above average. This is favorable for development of hurricanes, though not greatly so.

|

| Figure 2. Wind shear over the Atlantic of 8 am EDT August 12, 2019. Wind shear was very high, in excess of 40 knots, over the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, and was moderately high, 10 -20 knots, over the tropical Atlantic between the coast of Africa and the Lesser Antilles Islands. Image credit: University of Wisconsin CIMSS. |

Wind shear helping to keep things quiet for now

High wind shear acts to suppress hurricanes by imparting a shearing force that rips them apart. The latest wind shear analysis from the University of Wisconsin CIMSS (Figure 2) depicts prohibitively high wind shear for hurricane formation across the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, but moderately high wind shear acceptable for development over the tropical Atlantic between the coast of Africa and Lesser Antilles Islands. According to the latest forecast from NOAA’s CFSv2 long-range forecast model, wind shear across the tropical Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico will be above average for the coming ten days. then fall to near-average levels during the peak portion of hurricane season, from late-August through late-September. If this forecast verifies, it will mean favorable conditions for Atlantic hurricanes during the most dangerous part of the season.

El Niño events usually act to suppress Atlantic hurricane activity by creating strong upper-level winds over the tropical Atlantic that create high wind shear. As covered in our post on Thursday, NOAA signed the death warrant for El Niño on Thursday in its monthly discussion of the state of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which was headlined “Final El Niño Advisory”. The demise of El Niño boosts the odds for lower wind shear over the tropical Atlantic in the coming weeks, increasing the chances of an active hurricane season. Several forecast groups raised their predicted levels of activity for the Atlantic hurricane season last week, partially in response to the expected lower levels of wind shear.

|

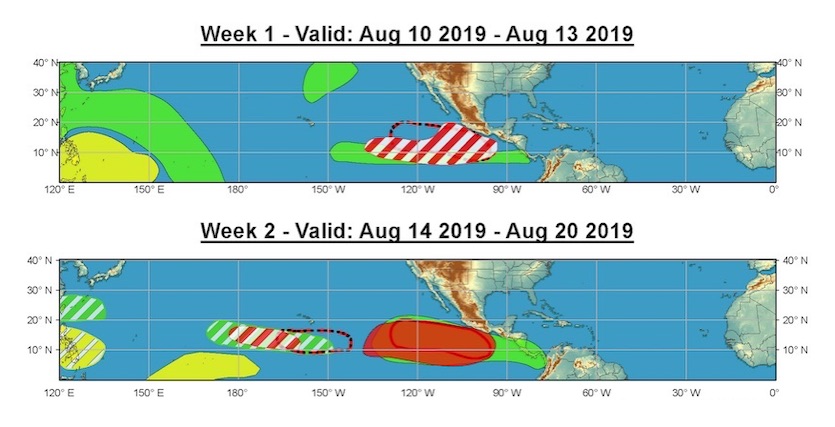

| Figure 3. The most recent update of NOAA’s Global Tropics Hazards and Benefits Outlook, released on Friday, August 9, 2019, shows a moderate-confidence outlook for tropical cyclone development in the East Pacific through August 13, with higher confidence in the following week (Aug. 14-20) together with chances of development emerging in the Central Pacific. The approach of a convectively coupled Kelvin wave (CCKW) is expected to favor development in these areas. Image credit: NOAA/CPC. |

The longer-range outlook: CCKW and MJO on the way

A specific tropical cyclone is impossible to predict with confidence more than a few days in advance, but there are other clues that give us a sense of how the next several weeks might unfold in the Atlantic. The most immediate threat would appear to be early next week in the northeast Gulf of Mexico, where a cold front is expected to stall out and potentially spawn a tropical depression. A similar situation existed to help with the formation of Hurricane Barry back in July. About 20% of the members of the 0Z Monday GFS ensemble forecast were giving support to a tropical depression spinning up in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico early next week.

|

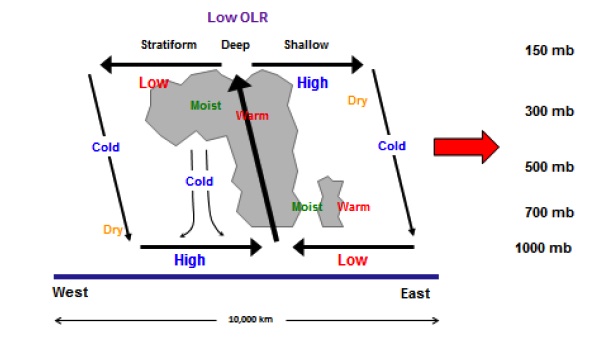

| Figure 4. Schematic cross section through a convectively coupled Kelvin wave (CCKW). Image credit: Michael Ventrice. |

A convectively coupled Kelvin wave (CCKW) now moving across the tropical Pacific is another feature we need to watch. CCKWs are large but subtle atmospheric impulses, centered on the equator, that roll eastward at 30-40 mph, with showers and thunderstorms typically along their forward flank. When an eastward-moving CCKW encounters a tropical wave, the enhanced moisture and upward motion may give it a boost and help it consolidate into a tropical cyclone.

The current CCKW in the Pacific could help one or more systems to develop in the Central and Eastern Pacific late this week into next week, as noted by NOAA (see Figure 3). In about 2-3 weeks, toward the end of August, this CCKW will be moving into the tropical Atlantic, where it could give an extra nudge to any tropical waves that have potential to develop.

For more on CCKWs, see this explainer post from the Cat 6 archives.

|

| Figure 5. A forecast of where rising motion (green) and sinking motion (tan) will predominate at high altitudes (around 200 mb or 39,000 feet) over the 40 days starting from 0Z Sunday, August 11, 2019. The forecast is based on a technique of calculating atmospheric wave propagation that reflects the behavior of the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO). Rising upper-level motion would tend to favor tropical cyclone development. Image credit: NOAA/CPC. |

Further down the timeline, we’ll need to watch the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), another large-scale couplet of rising and sinking air that travels through the global tropics from west to east about every 45 to 60 days. CCKWs are typically weaker but faster-moving than MJOs, so a CCKW can sometimes pass through an MJO region and the two can briefly reinforce each other.

Some indications from global models that the Atlantic will become more favorable by the end of the month as a CCKW (and maybe the MJO) move into the basin. Still very little ensemble support for TCs forming in the next 10 days, though, so we'll see if the hostile Atlantic wins. pic.twitter.com/38oSQ511Em

— Andy Hazelton (@AndyHazelton) August 12, 2019

The next MJO impulse is currently centered over the Maritime Continent, where it’s likely been helping to stimulate the spate of typhoons in the Northwest Pacific. The MJO is not especially strong right now, and it’s predicted to weaken as it moves toward the central Pacific over the next week or so, but it could restrengthen over time. If it adheres to typical MJO timing, this impulse should be affecting the Atlantic toward the end of August or early September. Depending on the MJO’s strength at that point, it could lead to a more active Atlantic than we’re seeing in early August.

|

| Figure 6. Damaged worker accommodation buildings are seen at a construction site in Wenling City, in China's eastern Zhejiang province, after being hit by Typhoon Lekima on August 10, 2019. Image credit: STR/AFP/Getty Images. |

China picking up the pieces after a multibillion-dollar hit from Lekima

At least 33 people have been killed in China, with at least 16 still missing, in the wake of Typhoon Lekima. The Category 2 storm slammed into the east central coast of China near Aiwan Bay early Saturday morning with 100-mph sustained winds, according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Some 1.7 millilon people were evacuated from Lekima’s path, according to China’s Xinhua news agency. As it swept north, Lekima passed about 30 miles west of downtown Shanghai—the world’s second largest city—while still a strong tropical storm.

Very heavy rains and floods from Lekima were widespread. According to the Associated Press, most of the deaths were in a village in Yongjia county, where a landslide blocked a river that then poured into the small town, killing 23 people. Major flooding also occurred in the city of Linhai. At least 34,000 homes and 173,000 hectares of cropland were damaged, and the estimated financial hit from Lekima is up to $2.1 billion in Zhejiang province alone, according to Steve Bowen (Aon), who tweeted: "Once impacts to other provinces are realized, this will end as a very expensive & impactful event."

A landslide occurs at an entrance to an expressway tunnel in Zhejiang, China, after Typhoon Lekima hit land pic.twitter.com/R1h3MtVQg0

— China Xinhua News (@XHNews) August 10, 2019

Lekima was comparable in landfall strength to Typhoon Chan-Hom, which struck near Zhoushan (80 miles south-southeast of Shanghai) as a 100-mph typhoon in July 2015. Chan-Hom was the strongest storm within 100 miles of Shanghai in at least 35 years, and Lekima is now tied with Chan-Hom as the strongest typhoon landfall on record for Zhejiang province in records going back to 1949. Because of its more easterly path, Chan-Hom moved over less land than Lekima before nearing Shanghai, but its track also kept Shanghai on Chan-Hom’s western (weaker) side, whereas the stronger eastern side of Lekima moved directly over Shanghai. Chan-Hom caused 18 direct and indirect deaths and a total of $1.58 billion in damage (2015 USD), most of that in China.

Bob Henson co-wrote this post.