| Above: Matt Harrington boards up a Vans shoe store near the French Quarter in New Orleans as Barry, then a tropical storm, approached on July 11, 2019. Barry ended up becoming the first hurricane of the Atlantic season. Image credit: Seth Herald/AFP/Getty Images. |

In updates released this week, several forecast groups have raised their predicted levels of activity for the Atlantic hurricane season. The end of the 2018-19 El Niño event is part of the picture, but other factors are involved as well.

NOAA signed the death warrant for El Niño on Thursday in its monthly discussion of the state of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which was headlined “Final El Niño Advisory”. During the past month, sea surface temperatures in the benchmark Niño3.4 region of the eastern tropical Pacific have trended below the El Niño threshold of 0.5°C above average. Water temperatures beneath the equatorial Pacific are near average, and low-level winds also reflect neutral conditions. “Overall, oceanic and atmospheric conditions were consistent with a transition to ENSO-neutral,” said the update.

The just-deceased El Niño event began in September-November 2018, as defined by the running three-month average of Niño3.4 temperatures. It remained a weak event throughout its life, with the top three-month average of +0.9°C just below the threshold for a moderate event of +1.0°C. Like many El Niño events, it began in northern fall and ended within about a year’s time.

Forecasters at NOAA and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) are calling for a roughly 55% chance of neutral conditions in winter 2019-20, with roughly 30% odds of El Niño returning and only about a 15% chance of a La Niña event. Neutral periods lasting more than a year are fairly infrequent; the only three such periods we’ve seen this century were in 2001-02, 2003-04, and 2012-14.

|

| Figure 1. Probabilities of El Niño (red), La Niña (blue), and neutral conditions (gray) for overlapping three-month periods from July-September 2019 (left) to March-May 2020 (right). Image credit: NOAA/IRI. |

NOAA bumps up its hurricane probabilities

In the update to its May outlook issued on Thursday, NOAA hiked the chances for a busier-than-usual hurricane season. The August outlook calls for a 45% chance of above-average activity and a 20% chance of below-average activity, as compared to the 30% odds projected in both categories in May. The chance of near-average activity has dropped from 40% to 35%.

NOAA is predicting the 2019 Atlantic season will produce 10 - 17 named storms, 5 - 9 hurricanes, and 2 - 4 major hurricanes, up slightly from the May totals of 9 - 15 named storms, 4 - 8 hurricanes, and 2 - 4 major hurricanes. The new forecast ranges take into account Hurricane Barry, which spun up in the Gulf of Mexico and reached minimal hurricane strength just before landfall on the Louisiana coast on July 13.

“El Nino typically suppresses Atlantic hurricane activity but now that it’s gone, we could see a busier season ahead,” said Gerry Bell, lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. “This evolution, combined with the more conducive conditions associated with the ongoing high-activity era for Atlantic hurricanes that began in 1995, increases the likelihood of above-normal activity this year.”

In a press conference, Bell noted that there is some persistence to El Niño-related weather patterns that can suppress Atlantic hurricanes, so part of the influence of the 2018-19 El Niño is already baked into the seasonal cake. However, the just-ended El Niño was a weak event to begin with. NOAA’s May forecast was predicted on a 60% chance of El Niño continuing, so the event’s demise helped push the August odds toward a busier-than-usual season, though a near-average season would still fall within NOAA’s forecast range.

|

| Figure 2. NOAA’s probabilities of an above-, near-, and below-average Atlantic hurricane season as of August 8, 2019. Image credit: NOAA. |

CSU: A near-average season

The August 5 update to the seasonal outlook led by Phil Klotzbach at Colorado State University (CSU)—last updated on July 9—also featured slightly higher numbers but was still in the near-normal range. CSU raised its predicted number of hurricanes from six to seven, owing to the formation of Hurricane Barry, and its accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) forecast from 101 to 105. The predicted number of named storms remained at 14, and CSU is still calling for two major hurricanes and five days of major-hurricane activity.

The three main components from July observations that are used by CSU in the statistical scheme for its annual August update are showing mixed signals this time around.

—Sea surface temperatures in the far eastern North Pacific were above average, an enhancing factor.

—Westerly high-level winds across Africa were stronger than usual, a suppressing factor.

—Trade winds in the Caribbean were very slightly stronger than average, a neutral factor.

The four seasons that best match the combination of factors above are 1990, 1992, 2012, and 2014. These years featured a wide range of activity—from 4 to 10 hurricanes and 7 to 19 named storms, with ACE values ranging from 67 to 133.

TSR: A near-average season

In line with other forecast groups, TropicalStormRisk.com is calling for a midrange outcome to the 2019 hurricane season, but skewed slightly toward a higher outcome. Like NOAA, they are calling for higher odds of an above-average season (29%) than a below-average season (26%), with those averages defined as the most and least active thirds of 1950-2018 ACE values. The midpoint of TSR’s ranges call for 13 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 100.

|

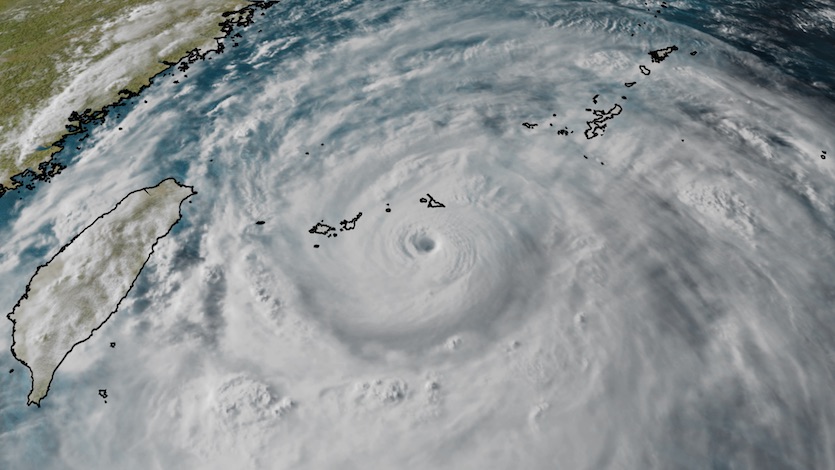

| Figure 3. Typhoon Lekima as it approached the Ryukyu Islands of southern Japan on Thursday evening local time, August 8, 2019. Image credit: weather.com. |

Powerful Lekima heading toward east central China

After peaking as a super typhoon with top sustained winds of 150 mph, Typhoon Lekima has continued churning toward the central China coast en route to a Saturday landfall. As of 18Z (2 pm EDT) Thursday, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center analyzed Lekima’s peak winds at 140 mph, with the storm’s center about 440 miles south-southeast of Shanghai.

Lekima passed through Japan’s Ryukyu Islands on Thursday night local time. The typhoon appeared to be going through an extended eyewall replacement cycle, with a distinct outer eyewall passing over the islands of Yaeyama on the left and Miyako on the right. The compact inner eyewall passed between the two, grazing the tiny island of Tarama. As reported by weather.com, winds had gusted to 104 mph at Miyako Shimojishima Airport as of early Friday morning local time, with sustained typhoon-force winds of 75 mph.

As it advanced, the storm’s central core carried out a dramatic sequence of looping wobbles—a vivid example of a phenomenon called trochoidal motion.

The trochoidal motion of the eye of Typhoon #Lekima gets more interesting toward the end of this 24-hour animation of 2.5-minute rapid scan #Himawari8 Infrared imagery: https://t.co/BkLqiMIXjM pic.twitter.com/6jaEKGGdS1

— Scott Bachmeier (@CIMSS_Satellite) August 8, 2019

Lekima is predicted to weaken to Category 2 or 3 strength before it moves over or near easternmost Zhejiang province and the Zhoushan Archipelago. As it quickly recurves northward, the storm could go on to make a direct hit on Shanghai, the world’s second largest city. Fortunately, the center would have passed over coastal land for about 12 hours beforehand, so Lekima would likely be no more than a tropical storm at that point.

Lekima’s predicted strength and track as it approaches China is roughly similar to that of Typhoon Chan-Hom in July 2015. Chan-hom made landfall about 80 miles south-southeast of Shanghai with top winds estimated by JTWC at 100 mph, making it the strongest typhoon within 100 miles of Shanghai in at least 35 years and the strongest to make landfall in Zhejiang province. Chan-hom produced wind gusts to 56 mph at Shanghai Pudong International Airport. The storm caused one death and left more than $1 billion USD in damage across eastern China.

Sunrise on the 2 strongest storms on the planet, synchronized swirls: Typhoons #Lekima & #Krosa in the NW Pacific. Updates at https://t.co/l3ufufW4d7 pic.twitter.com/P4N6WrfoCI

— UW-Madison CIMSS (@UWCIMSS) August 8, 2019

The presence of Typhoon Krosa well to the east of Lekima made for a dramatic pairing. Krosa was a Category 3-equivalent typhoon as of 21Z Thursday, with top sustained winds holding steady at 115 mph. Krosa’s track will carry out a slow, compact cyclonic loop before the typhoon accelerates toward Japan early next week, likely weakening to tropical storm strength before any landfall.