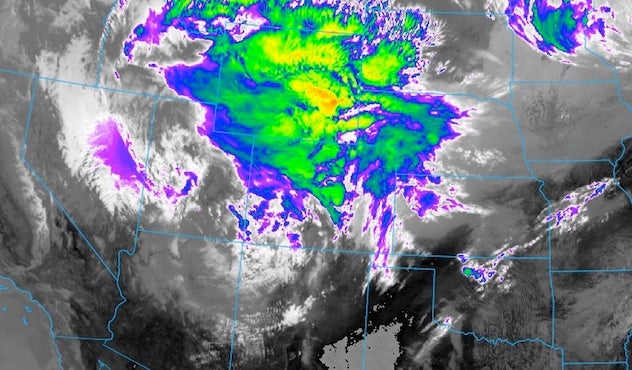

| Above: An infrared GOES-16 satellite image from 1512Z (10:12 am CDT) Thursday, May 18, 2017, shows the strong upper-level low in the southwestern U.S. that will produce heavy snow and severe weather. GOES-16 images are preliminary and non-operational. Image credit: NOAA, via Next Generation Weather Lab/College of DuPage. |

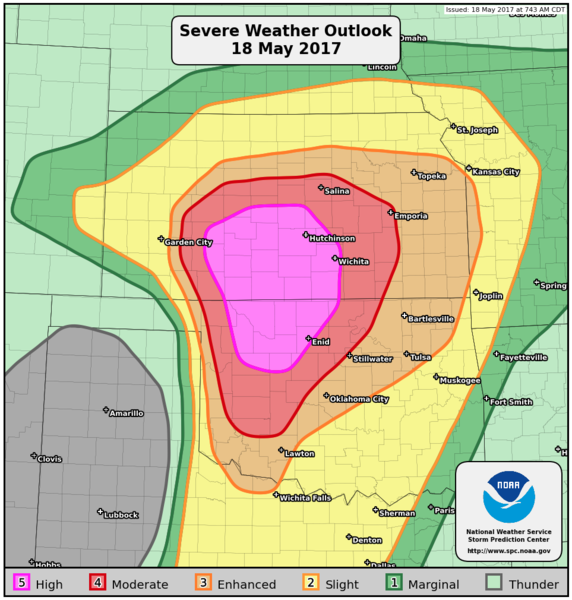

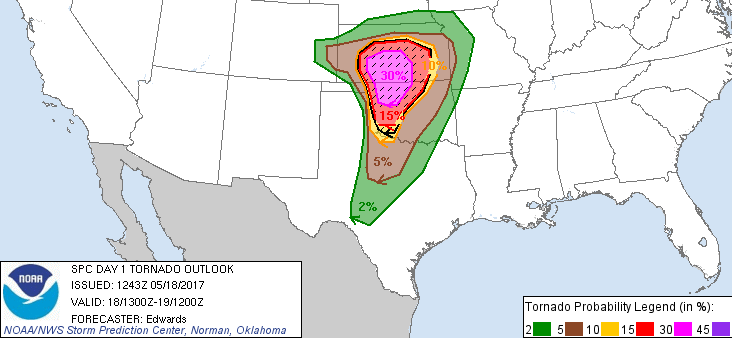

The NOAA/SPC Storm Prediction Center is calling for a high risk of severe weather—the most dire rating possible—for parts of Kansas and Oklahoma for Thursday (Figure 1). Lesser but still major risk surrounds the high-risk zone. Strong, long-track tornadoes are a distinct threat for Thursday (see Figure 2).

A potent upper-level storm moving through the southwest U.S. is in position to create two types of extreme weather: supercell thunderstorms in the Southern Plains, with a risk of significant tornadoes, as well as an intense spring snowstorm already affecting the Front Range north and west from Denver, Colorado.

|

| Figure 1. Thunderstorm risk areas for Thursday, May 18, 2017, as updated by NOAA/SPC at 7:43 am CDT. |

|

| Figure 2. Probabilities of a tornado within 25 miles of any given point from Thursday, May 18, 2017, into Friday morning. Hatched areas indicate at least a 10% chance of one or more significant tornadoes (EF2 or greater) within 25 miles of a point. There is a 2% chance of tornadoes across parts of the Great Lakes (not shown). Image credit: NOAA/NWS/SPC. |

Severe storms a virtual lock, but how will they evolve?

There is very little doubt that widespread severe storms will occur across the high-risk area. Large-scale and high-resolution models agree that energy from the Southwestern upper-level storm will kick out across the Great Plains on Thursday afternoon and evening. Very moist, unstable air surged northward overnight across Texas and Oklahoma. The dew point at Oklahoma City shot up from a comfortable 52°F at 2 am CDT Thursday to a muggy 67°F at 5 am.

Atmospheric soundings launched at 12Z (7:00 am CDT) Thursday confirm a classic profile for producing severe storms: a very warm, moist layer about a half-mile to one mile deep, overtopped by a thin “cap” of warm, dry air that keeps the instability bottled up until daytime heating and/or a frontal system kick off storms. Today’s conditions should have little trouble breaking the cap.

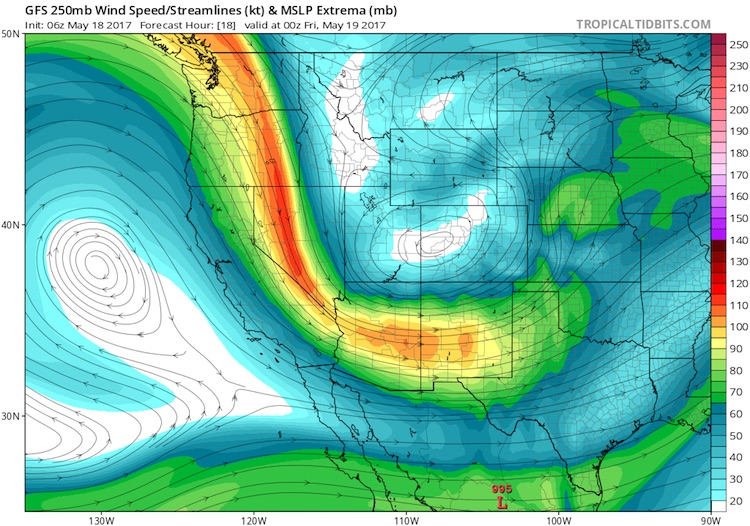

Vertical wind shear that favors rotating storms is already present across the risk area, and it will spike markedly by Thursday afternoon as low-level winds crank up and the upper-level system approaches. Wind shear will be at very high levels by later afternoon across the higher risk areas.

|

| Figure 3. The nose of the jet stream at 250 mb (about 34,000 feet) will be punching into the Southern Plains on Thursday evening, May 18, 2017, as depicted by the 06Z Thursday run of the GFS model. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

Perhaps the biggest question is how the character of today’s severe storms will evolve. The most serious tornado-producing thunderstorms are discrete supercells, located far enough from other thunderstorms so that the immediate environment nurtures and supports the supercell. Thursday’s atmosphere certainly has all the ingredients for powerful tornadic supercells. The expectation is that supercells may form along a warm front located in southern Kansas and/or along a dryline sharpening in western OK and KS. Isolated supercells could pop further south and east as well, just ahead of these boundaries. Although the probability of tornadic storms drops as you go southward along the dryline into northwest TX, any fairly isolated supercells here could end up just as intense as those further north.

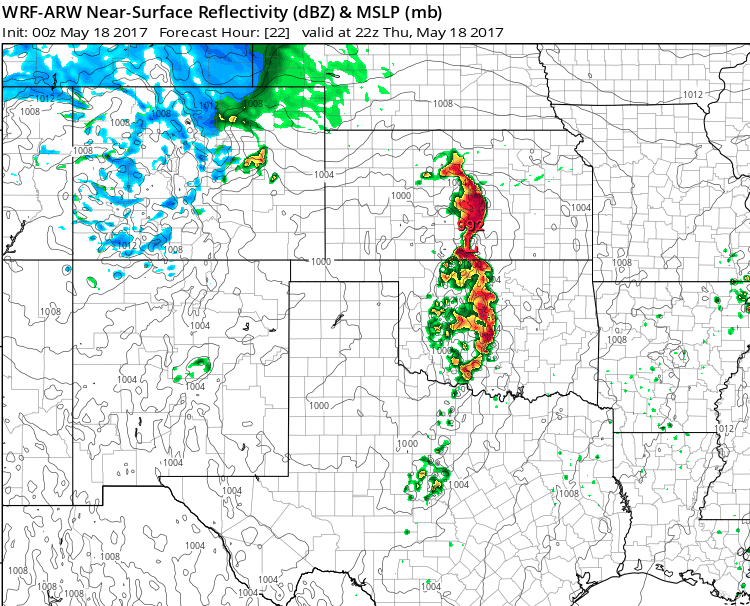

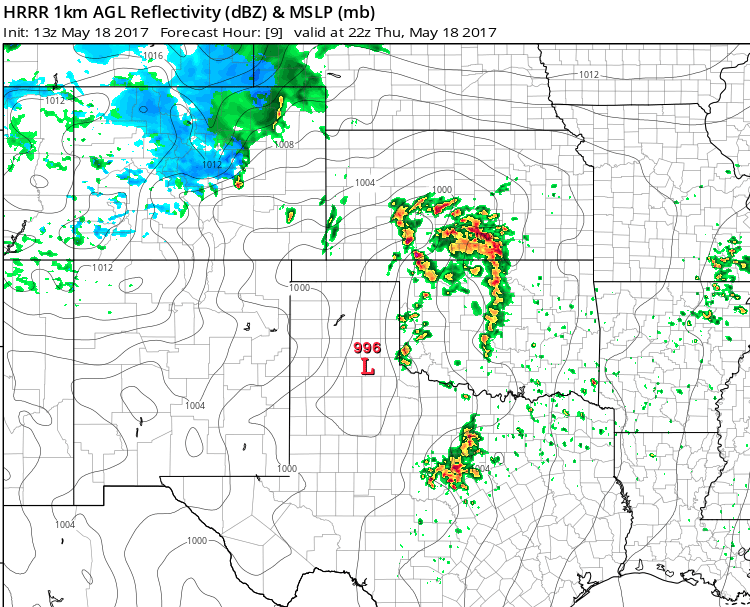

Dense concentrations of severe thunderstorms can produce huge hail, extreme wind, and even tornadoes, but the messier nature of this mode tends to limit the threat of violent tornadoes. Complicating Thursday’s setup is that some runs of the highest-resolution models such as WRF-ARW and HRRR—which are the best at portraying how thunderstorms will evolve from hour to hour—have depicted early development of widespread severe storms (between about noon and 2 PM CDT) that quickly expand northeast. Often, as was the case on Tuesday in KS/OK/TX, tornadic supercells develop from north to south; this allows the later southern storms to maintain unimpeded access to unstable air that flows north. A south-to-north development mode could allow more intra-storm interference.

|

| Figure 4. Thunderstorm locations depicted in the high-resolution WRF-ARW model run from 00Z Thursday, valid at 22Z (5:00 pm CDT) Thursday, May 18, 2017. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

|

| Figure 5. Thunderstorm locations depicted in the high-resolution, high-frequency, HRRR model run from 13Z Thursday, valid at 22Z (5:00 pm CDT) Thursday, May 18, 2017. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

In its 7:43 am CDT update, SPC cautioned: “Initiation of too many cells in early/middle afternoon…and/or too close to each other at once, is possible in some parts of the current moderate/high risks. This scenario, which some guidance suggests, would lend a greater wind threat and somewhat suppressed hail/significant-tornado risk with eastward extent, due to messier storm modes amidst strengthening deep-layer flow.”

|

| Figure 6. The matrix used by forecasters at the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center to determine convective risk areas. After assigning probabilities to the likelihood of tornadoes, hail, and high wind, forecasters use this matrix to determine risk areas, with some leeway for expert judgment. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/SPC. |

Given the volatile atmospheric conditions on hand Thursday, we must proceed assuming that the highest-end types of severe weather are possible, and hope that the storms get in each others’ way enough to tamp down the potential. NOAA/SPC has issued a public severe weather outlook summarizing the threats.

The changing nature of SPC’s high risk outlooks

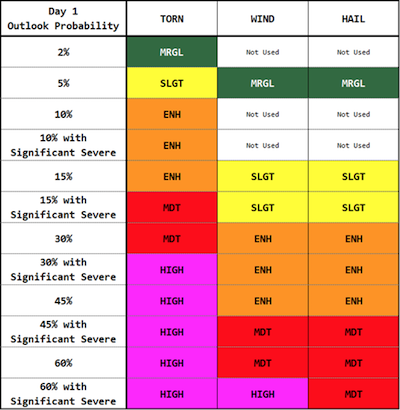

The key variables with a high risk are coverage and intensity: severe weather events are expected to be both very strong and very numerous within the risk area. Although SPC focuses mainly on tornadoes when considering the issuance of a high risk, extreme wind and hail also play into the SPC outlooks (see Figure 6).

Thursday’s high-risk area is the fourth issued by SPC this year; two of the other three were quite small in area. SPC’s warning coordination meteorologist, Patrick Marsh, discussed the high-risk categories in an interview this week in Capital Weather Gang. Typically, says Marsh, “A high risk is a forecast of at least 30 percent coverage of tornadoes and at least 10 percent coverage of significant tornadoes (EF-2 or stronger).” In theory, a very intense derecho that is likely to produce destructive wind over a large swath could lead to a high risk, as shown in the matrix at right.

Years ago, high-risk areas tended to be issued early in the day for large areas where tornado risk was especially high. However, “as the science of tornado forecasting continues to improve, SPC forecasters are increasingly able to identify smaller corridors of heightened tornado potential further in advance,” said Marsh. The flip side, he added: people who are accustomed to the more traditional large high-risk areas may feel an event was over-hyped when only a few tornadoes occur (even if those are enough to confirm that a small high-risk area was justified).

|

| Figure 7. Malina the husky strolls through a wintry landscape near Nederland, CO, on Thursday morning, May 18, 2017. About 16” had fallen by 8:30 am MDT. Image credit: Courtesy Carlye Calvin. |

|

| Figure 8. A snowy sunrise in Coal Creek Canyon, several miles west of Boulder, Colorado. About 8” had fallen when this photo was taken. Image credit: Courtesy Peggy Stevens. |

Winter crashes the party in Colorado

Just as it was feeling like spring in northern Colorado, winter has returned for one last swipe—perhaps a historic one. On the north side of the powerful Southwestern upper low, easterly winds were slamming moisture upslope on Thursday morning against the Rocky Mountain Front Range west and north of Denver. Temperatures dropped a bit more than expected in the Denver-Boulder urban corridor on Wednesday night, down to near the freezing mark. Heavy snow was falling by morning in Boulder and nearby areas, with more than a foot already on the ground in the vicinity of Nederland.

This storm has the potential to drop truly impressive amounts of snow for so late in the year. Models are in strong agreement that precipitation will continue into Friday morning, and heavy precipitation rates will help keep the atmosphere chilled. Even if the snow mixes with or turns to rain in Front Range towns and cities during the day, an extended period of snow appears likely on Thursday night. A winter storm watch is in effect for Denver, one of the latest such springtime watches in memory to affect a major U.S. metro area.

Accumulations will vary widely depending on elevation and on when, where, and how hard it snows, but many urban areas could see a few inches—enough to break tree limbs and bring down power lines. In the foothills, several feet of snow are quite possible.

A foot of snow could fall in Boulder, but even that may not quite break records, as noted by Boulder weather observer Matt Kelsch in his blog. “Although it is unseasonably late for snow and freezes, it is not rare,” Kelsch said in a post on Tuesday. “In Boulder there have been two measurable snows recorded in June (the latest of 1.0 inch on June 12, 1947). On May 20-21, 1931 there was a 19-inch snowfall in Boulder (the trees must've loved that).”