| Above: Libyan youths watch a solar eclipse in a desert tourist camp in Galo, about 800 miles south of the Libyan capital of Tripoli, on March 29, 2006. Thousands of astronomers and thrill-seekers gazed heavenward, prayers were said by the faithful, and schools shut for the day as the celestial ballet raced across half the world. Image credit: Khaled Desouki/AFP/Getty Images. |

The first coast-to-coast total eclipse to grace the United States in nearly a century will sweep across the landscape on Monday, August 21—and, to say the least, word is getting out. Some eclipse fans from across the nation and the world made their hotel reservations literally years ago. Others started thinking only a few days or weeks ago about venturing into the total-eclipse path. Millions of Americans won’t have to go anywhere, as the narrow path of this eclipse will pass over a number of big cities and small towns (see the embedded YouTube video below).

Two minutes of transcendence

Experiencing totality—when the moon completely obscures the solar disk for two minutes or more, depending on location—is a very rare treat. “Words often fail when trying to explain the kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, feelings and emotions that consume us during this other-worldly event,” says NASA scientist emeritus Fred Espenak, a.k.a. “Mr. Eclipse.” In a post for EarthSky, Espenak featured an excerpt from Total Eclipses of the Sun, 1894, by 19th-century U.S. writer Mabel Loomis Todd. Her description is spine-tingling and well worth reading in full. Here’s an excerpt of the excerpt:

“…A vast, palpable presence seems to overwhelm the world. The blue sky changes to gray or dull purple, speedily becoming more dusky, and a death-like trance seizes upon everything earthly. Birds with terrified cries, fly bewildered for a moment, and then silently seek their night quarters. Bats emerge stealthily. Sensitive flowers, the scarlet pimpernel, the African mimosa, close their delicate petals, and a sense of hushed expectancy deepens with the darkness...”

|

| Figure 1. Most photographs don't adequately portray the magnificence of the Sun's corona. Seeing the corona first-hand during a total solar eclipse is best. The human eye can adapt to see features and extent that photographic film usually cannot. The above picture is a combination of thirty-three photographs that were digitally processed to highlight faint features of a total eclipse that occurred in March of 2006. The images of the Sun's corona were digitally altered to enhance dim, outlying waves and filaments. Image credit: © Koen van Gorp, via NASA. |

|

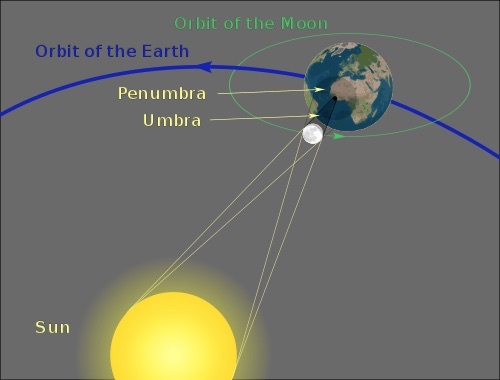

| Figure 2. Geometry of a total solar eclipse. The umbra is the shadow caused by the moon completely obscuring the Sun, whereas the broader, fainter penumbra leads to a partial eclipse. The sizes and distances in this image are not to scale. Image credit: Sagredo/Wikimedia Commons. |

Why it happens

The fact that we get total solar eclipses at all can be chalked up to an epic celestial coincidence. Our moon is nearly 400 times closer to Earth than the Sun is (238,900 mi vs. 92.96 million mi). However, the moon’s diameter is about 400 times smaller than the Sun’s (2159 mi vs. 864,575.9 mi), which means the lunar and solar disks as viewed from Earth are nearly the same size.

Because the two relevant orbits—Earth around the Sun, and the moon around Earth—are slightly elliptical, there’s enough play in the system to produce total eclipses as well as annular eclipses, which occur when the lunar disk doesn’t quite cover the Sun.

In this Category 6 post, WU weather historian Christopher Burt reviews the handful of total and annular solar eclipses affecting the United States since the mid-1800s.

We should enjoy total eclipses while we can, because the ever-so-gradual spinning down of Earth means that the moon is moving ever so slightly farther from us. We have only about 650 million years left before the moon will be too far away to produce a total eclipse!

About 12.25 million Americans live within the path of totality for the August 21 eclipse, which will stretch from Oregon to South Carolina. However, everyone in the United States—including Alaska and Hawaii—will get a chance to experience at least a partial eclipse. Across the entire 48 states of the contiguous U.S., the moon will obscure more than half of the solar disk. “The vast majority of Americans will see at least a 70% obscured partial eclipse,” notes americaneclipseusa.com. “Over the two-hour duration of partial eclipse, the daylight will become grey and feeble, and the colors of daylight will appear washed out.”

If you're heading for the totality zone, it's a good idea to get at least a few miles within the boundaries, in order to maximize your time in totality and to avoid mapping errors that could shave as much as a half-mile off each side of the totality zone.

|

| Figure 3. A partial solar eclipse behind thin clouds, photographed from near La Dole, Switzerland, in May 1994. Image credit: Caspar Ammann/UCAR Digital Image Library. |

We can’t do much about the weather on August 21, and for some areas we may not be able to tell whether it’ll be cloudy or sunny until just hours before the event. Climatology does gives us some good clues about what to expect, though. Overall, the seasonal and diurnal timing of this eclipse are quite favorable. For instance, much of the path will experience the eclipse within a couple of hours of local noon. This will maximize the drama of totality’s darkness while lowering the odds of summer showers and thunderstorms, which tend to develop later in the afternoon and evening. At the website eclipseophile.com, Jay Anderson and Jennifer West provide a superb, detailed guide to the terrain and the climatological factors at work in each state along the path of totality.

|

| Figure 4. Members of the public scramble for free eclipse viewing glasses at Regent's Park in central London ahead of a partial solar eclipse on March 20, 2015. Hundreds of people optimistically gathered to view the rare solar event, but the views were spoiled by thick clouds. Image credit: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images. |

Eclipse logistics: How to stay safe wherever you are

At greatamericaneclipse.org, Michael Zeiler shows us the potential for traffic trouble before and after the big event. Some 200 million people live within a day’s drive of the path of totality, and Zeiler estimates that somewhere between 1.8 and 7.4 million people will be driving into the path. “Imagine 20 Woodstock festivals occurring simultaneously across the nation,” says Zeiler. “Large numbers of visitors will overwhelm lodging and other resources in the path of totality. There is a real danger during the two minutes of totality that traffic still on the road will pull over at unsafe locations with distracted drivers behind them.”

Nobody knows how many folks will take to the roads, but Zeiler sees good reason to expect that quite a few will:

- “The path of totality cuts a diagonal path across the nation from Oregon to South Carolina and most Americans live within a day's drive to the path of totality.

- “The United States has an excellent highway system and most American families have it within their means to take a short driving vacation.

- “August is an ideal month for a vacation; the weather is warm and the chance of summer storms has diminished in much of the nation.

- “Most schools have not yet begun their fall session by August 21st and some schools near the path of totality are scheduling a late start.

- “Social media will have a huge impact on motivating eclipse visitors. The eclipse is exactly the type of event guaranteed to go viral on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and other social platforms. We expect that many people will only make plans to go in the week before eclipse day.”

The Federal Highway Administration, which has a website devoted to the eclipse, advises state and local transportation departments to see the eclipse as “a planned special event for which there has been no recent precedent in the United States.” It suggests that “travelers should be at their observation location a minimum of a couple hours before totality. The role of state and local DOTs may include instituting roadblocks or other measures to keep people from making illegal turns as they drive around looking for ‘the perfect spot’ as eclipse totality nears.”

Since driver behavior will be even less predictable than usual during the eclipse, motorists and pedestrians should be on guard for distracted drivers, and vice versa. South Carolina weathercasters Jim Gandy and Efren Afante (WLTX, Columbia) put together a short video summarizing other safety tips for motorists within totality. Columbia, SC, is one of five state capitals in the path of totality, along with Nashville, TN; Jefferson City, MO; Lincoln, NE; and Salem, OR.

One thing is certain: to avoid potential eye damage, special-purpose solar filters MUST be used to view the crescent-shaped sun during a partial or annular eclipse. It’s also unsafe to look through a camera viewfinder, which concentrates the solar rays. The only time in which it’s safe to look directly toward the sun is during the totality phase of a total eclipse, when the solar disk is completely covered by the moon and all that is visible is the tendrils of the solar corona. NASA has an extensive, definitive website on eye safety during the eclipse, including which eclipse glasses are certified for use.

|

| Figure 5. Stargazers in and near south and central Africa—including the town of Saint-Louis, on the Indian Ocean island of La Reunion—were treated to an annular solar eclipse on September 1, 2016. Unlike a total eclipse, when the Sun is blacked out, sometimes the moon is too far from Earth, and its apparent diameter too small, for complete coverage. Image credit: Richard Bouhet/AFP/Getty Images. |

Partying and crowdsourcing

There’s much more to this event than the eclipse itself. Hundreds of local gatherings and festivals are in the works, many of them stretching across the entire weekend into Eclipse Day. Some of the most noteworthy goings-on are compiled at nationaleclipse.com.

One of the coolest projects associated with the eclipse is a citizen-science effort called the Eclipse Megamovie. It will stitch together many hundreds of eclipse images from professionals and volunteers across the United States. Although the official photo team is in place for the project, you can still submit your photo of the sun during totality, and you can use the Eclipse Megamovie app on your Android or iOS phone to automatically take photos. For details, see eclipsemega.movie.

As for your Category 6 gang, we’ll be distributed far and wide. Jeff Masters will be in western Kentucky; I’m heading to central Nebraska; and Chris Burt is joining WU co-founder Perry Samson at Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming.

Open thread!

What do you have planned for Eclipse 2017? Let us know in the comments thread below. We're keeping this Disqus comment thread focused on the eclipse. To chime in on tropical cyclones or other topics, see the main Category 6 page for our most recent non-eclipse post.