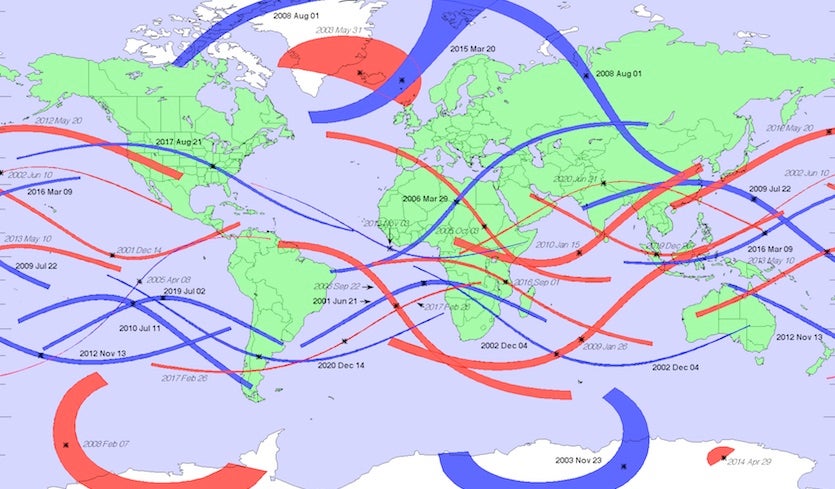

| Above: This NASA image shows the track of every total and annular solar eclipse from 2001 to 2020. Blue paths above show where the sun will be completely blocked for each total eclipse, including the one that will pass across the United States on August 21, 2017. The sun and moon are almost exactly the same size when viewed from Earth, which is why we get total eclipses. However, because of small orbital variations, the moon does not always fully obscure the sun during some eclipses. This results in an annular eclipse, where a "ring of fire" (annulus) is seen around the edge of the moon. Red colors above denote annular eclipse paths. Image credit: Fred Espenak/NASA. |

On August 21, the continental United States will host one of the most spectacular total solar eclipse events to have occurred since the arrival of Europeans to its shores. Given there has not been a total solar eclipse in the continental U.S. since 1979 (and that one was almost entirely unseen due to clouds and rain along its path across the Pacific Northwest), the coming event is likely to be one of the most well-documented eclipses in U.S. history. This, of course, is given the advent of digital photography, smart phones, and social media since the last total eclipse mentioned above.

Here is a look back at previous total solar eclipses to affect the continental U.S. since the middle of the 19th century, when astronomy began its modern era of observation. We will be looking only at total eclipses below. However, as shown in the image at top, there are also annular solar eclipses—those where the moon and sun are lined up perfectly but the moon does not completely cover the sun. These occur because of slight orbital variations that take the moon too far from Earth, and/or the Sun too close to Earth, for a total eclipse.

There have been 15 total eclipse events to affect at least a portion of the continental U.S. over the past 150 years (since the year 1867). These were in 1869, 1878, 1889, 1900, 1918, 1923, 1925, 1930, 1932, 1945, 1954, 1959, 1963, 1970, and 1979. Of these, only one traversed the entire country coast-to-coast: the event of 1918.

Below are some details about each of these previous events. Wikipedia has more details on each eclipse, which can be reached from its 19th century summary page and 20th century summary page. Unless otherwise noted, these pages also include all of the images below, as created by NASA’s Fred Estenpak. Paths of totality are bounded in blue.

1869 (August 7): The path of totality entered the contiguous U.S. over North Dakota and exited over North Carolina. The path also included Alaska, where astronomer and explorer George Davidson observed the eclipse in the Chilkat Valley.

|

1878 (July 29): This major eclipse event was one of the first to be extensively observed in the U.S. using scientific instruments. Wyoming was the focus of an expedition to record the event, and this is brilliantly described by David Baron in his just-published book American Eclipse: A Nation’s Epic Race to Catch the Shadow of the Moon and Win the Glory of the World.

|

1889 (January 1): The path of this famous “New Year’s Day Eclipse” came ashore just north of San Francisco and passed into Canada from extreme northwest North Dakota. The newly designated Yellowstone National Park was in the path of totality—something it will just miss this August, as the path will be just to the south over Grand Teton National Park (where I will be for the event, along with Weather Underground co-founder Dr. Perry Samson).

|

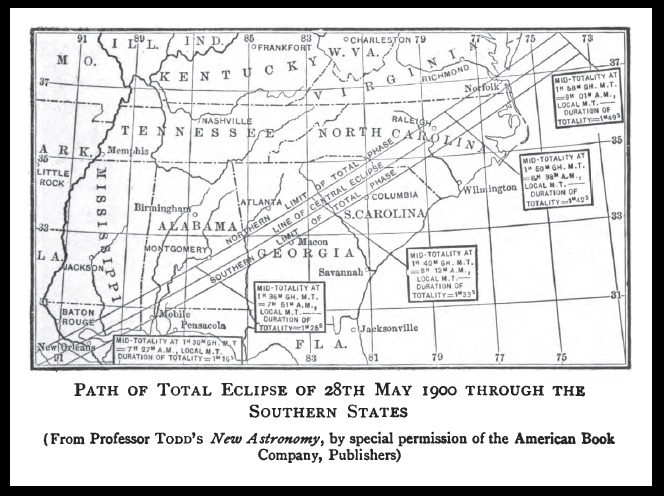

1900 (May 28): Total eclipse over a portion of the Southeast U.S. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, along with photographer Thomas Smillie, launched a major expedition to observe and photograph this event. The project was dubbed an “exceptional scientific achievement” at the time. Image credit: From New Astronomy, via Wikimedia Commons.

|

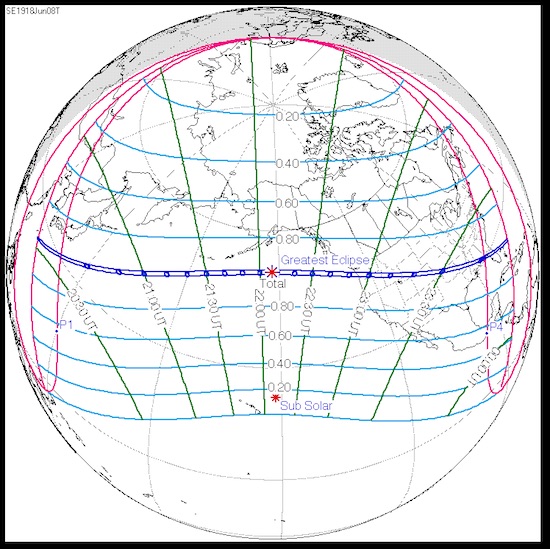

1918 (June 8): The most recent great transcontinental total eclipse traversed the U.S. from Washington State to Florida. Totality was observed in Denver.

|

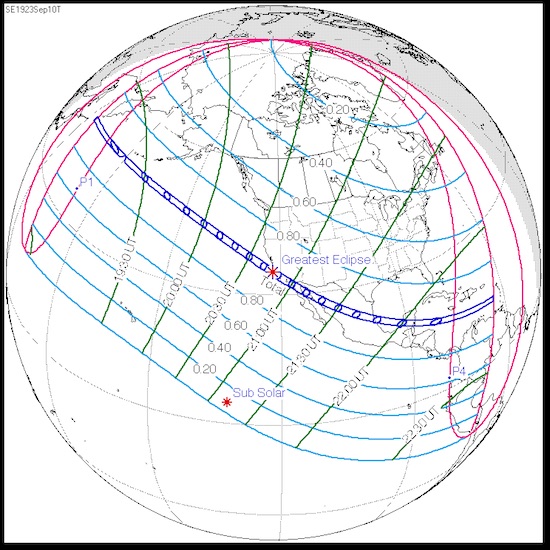

1923 (September 10): The path of totality just barely glanced a small portion of the southern California coastline at Lompoc.

|

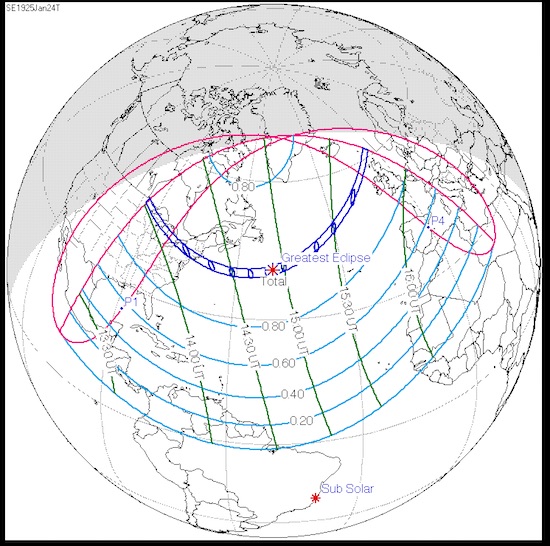

1925 (January 24): Path of totality swept across portions of Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and New York State, including New York City, where totality was achieved north of 96th St. in Manhattan.

|

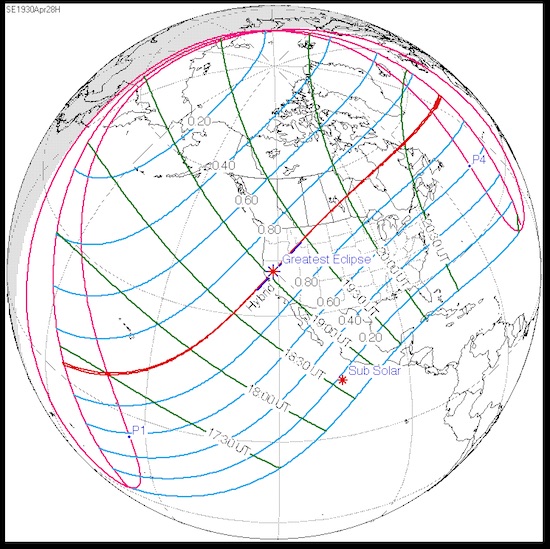

1930 (April 28): This was a “hybrid” eclipse event, meaning that it started off and finished up as an annular eclipse rather than being a total eclipse for the entire duration. The path came ashore in northern California and exited the U.S. into Canada via central Montana.

|

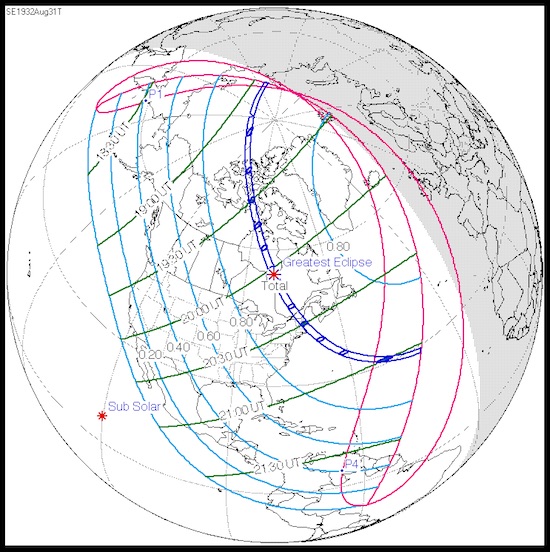

1932 (August 31): The path of totality during this event clipped only a small portion of the Northeast, including Vermont, New Hampshire, and southern Maine.

|

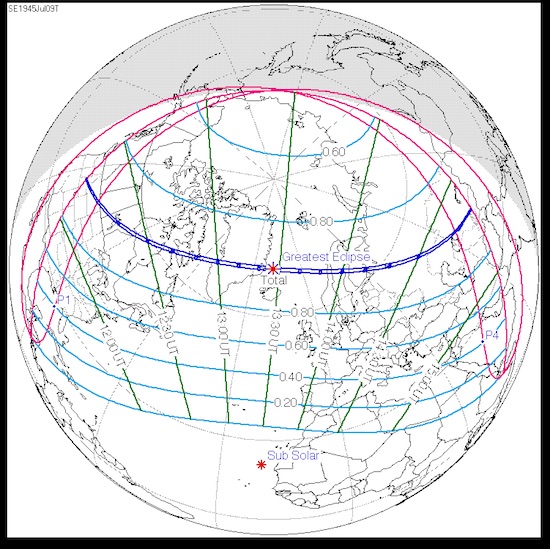

1945 (July 9): Only a very small portion of Idaho and Montana saw totality, just at sunrise and for only about an hour, before the eclipse moved into Canada.

|

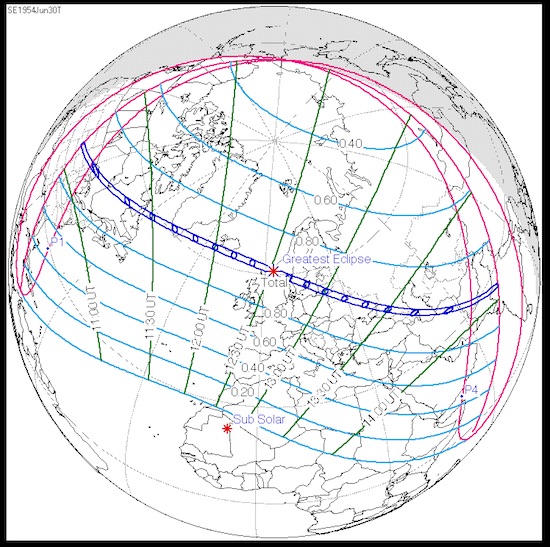

1954 (June 30): Like the 1945 event, the total eclipse became visible in the U.S. only just at sunrise over eastern Nebraska before exiting the U.S. via Wisconsin and Minnesota. The event was a big deal in northern Europe, where the peak of the event occurred in Norway and Sweden.

|

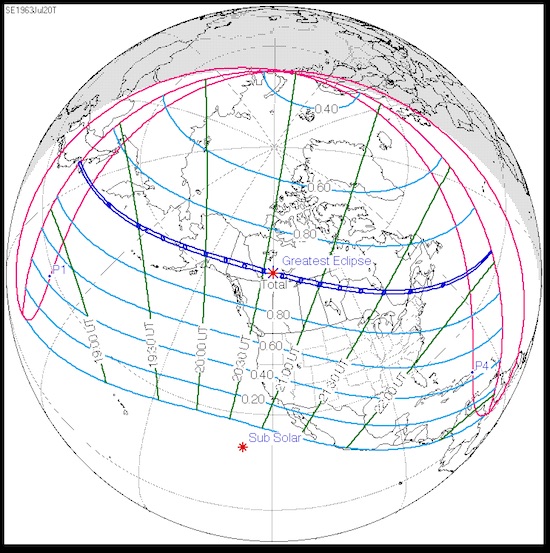

1963 (July 20): In the continental U.S., only central Maine saw a total eclipse during this event, although the path of totality bisected Alaska.

|

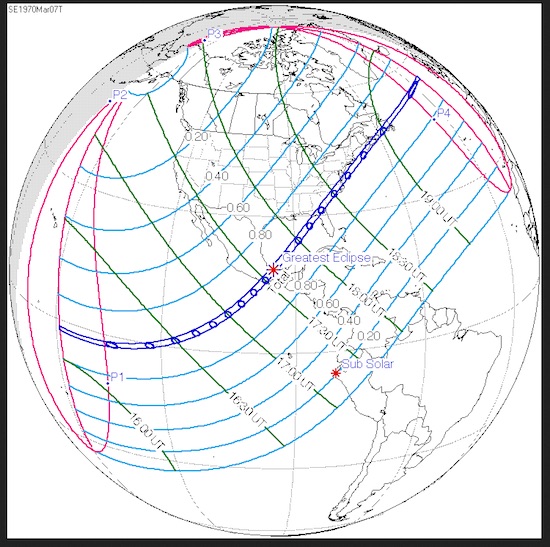

1970 (March 7): This is probably the last total eclipse that anyone reading this blog in the U.S. might remember. The path of totality came ashore over the Florida panhandle and marched up the Atlantic East Coast before going offshore over Norfolk, Virginia. It provided 90% totality to the big East Coast corridor cities from Washington D.C. to Boston. Charleston, South Carolina was in the 100% totality zone, as it will be again this August. This eclipse may have served as the inspiration for the line “Then you flew your Learjet up to Nova Scotia to see the total eclipse of the sun,” in Carly Simon’s #1 pop hit “You’re So Vain,” which was written in 1971 and recorded in 1972 (although Nova Scotia also experienced a total solar eclipse on July 10, 1972).

|

1979 (February 26): The path of this rare wintertime total eclipse coursed across Washington State, northern Idaho, and Montana before entering Canada from extreme northwest North Dakota. A large Pacific storm was affecting the region, and the sun was never clearly visible along the route.

|

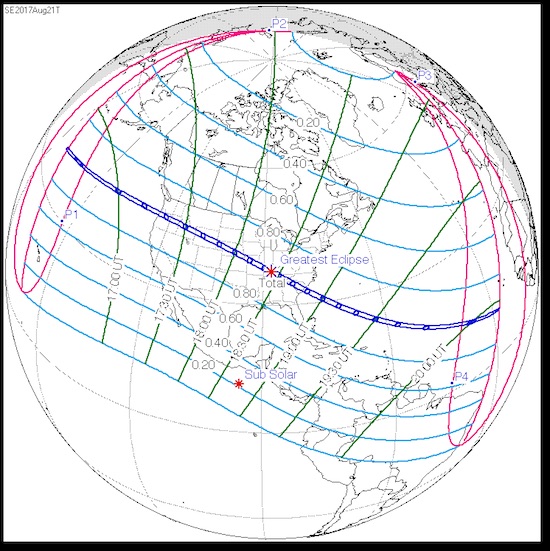

2017 (August 21): And, of course, the big one of this year.

|

Coming up: Total eclipses that will affect the U.S. after 2017

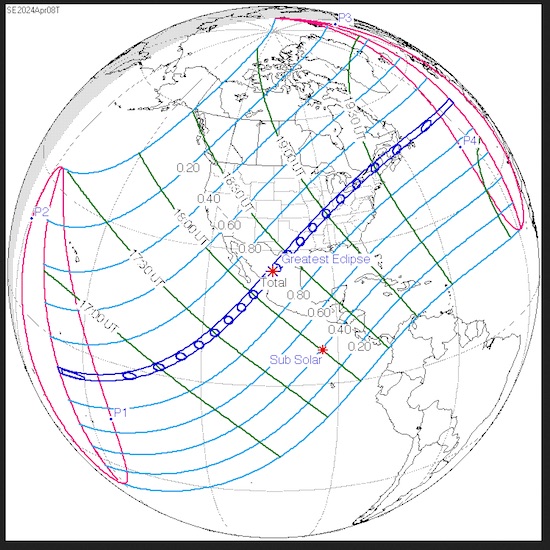

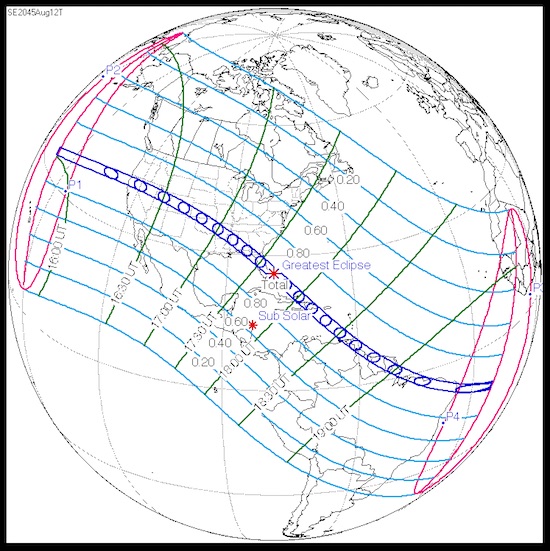

As can be seen from the list above, total solar eclipses are rare events in the U.S., let alone ones that cross significant portions of the country. So it is surprising that the next two such events are coming up relatively soon and, once again, will be visible to millions of Americans. These are the total eclipses of April 8, 2024 and August 12, 2045. Here are their paths:

2024 (April 8): The path of this coming-very-soon total eclipse will intersect the path of the 2017 event in and near Carbondale, Illinois. So those lucky residents don’t have to travel anywhere in order to experience TWO total solar eclipses in the span of just seven years!

|

2045 (August 12): Note how the path of this eclipse is almost identical to the 2017 event though traversing the continent about 200 miles further to the south.

|

Jeff Masters and Bob Henson will be posting more about the 2017 event over the course of the next month. Stay tuned!