| Above: The total solar eclipse as viewed from southeast Wyoming. Image credit: Carlye Calvin, used with permission. |

The solar eclipse that swept across the U.S. on Monday, August 21, may have been the most thoroughly documented in world history. Millions of people saw the event broadcast live from multiple vantage points on The Weather Channel or caught the livestream featured on TWC mobile apps (in partnership with Twitter) and at weather.com. Millions more trekked to the path of the total eclipse, or enjoyed the partial eclipse from home, school, or a community event. At least 60% of the sun was blocked by the moon at every point in the contiguous United States.

|

| Figure 1. Denver-based physician and photographer Jason Persoff captured this scene with a 14-mm wide-angle lens during the eclipse from a vantage point 4 miles south of Agate, Nebraska. "I cannot quite figure out how to describe the lighting," Persoff said. "The shadows were so sharp, but the lighting looked so muted." He added: "The corona was so diamond-white and chiseled. It extended far out from the sun—much farther than I could believe." Image credit: © Jason Persoff (stormdoctor.com), used with permission. |

There’s no way to do justice to this extraordinary societal and astronomical event in a single post, but we’d like to highlight one of the more striking aspects of the eclipse: its effect on local weather. Many locations around the country saw temperatures drop by several degrees Fahrenheit during the roughly two hours of the eclipse. Along the path of totality, the decrease was even more marked. This was fully expected—but it seems certain that eclipse-generated weather has never been predicted, documented, and analyzed so thoroughly in so many locations.

Beneath clear skies in Salem, Oregon, temperatures dropped about 3°F during the eclipse, as reported by the National Weather Service in Portland. Further east, where the eclipse arrived during the heat of the early afternoon, the temperature drop was more dramatic. Some examples posted by NWS Nashville:

Clarksville, TN: 6°F drop

Nashville, TN: 5°F drop

Crossville, TN: 7°F drop

As part of an eclipse expedition in Newberry, South Carolina, NWS staff took five-minute temperature readings that showed a drop from 95°F at the start of the partial eclipse (1:10 pm EDT) to 85°F during totality (2:40-2:42 EDT), then a further drop to 84°F for about 15 minutes afterward before a rebound back into the 90s. The data gathered in the Newberry expedition will be compared to observations collected by the U.S. Weather Bureau and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts & Sciences during a total eclipse on May 28, 1900. Thanks go to Frank Alsheimer, science and operations officer at the NWS office in Columbia, SC, for this information.

There goes the sun

As one might expect, the amount of incoming solar radiation dropped much more drastically than the surface temperature. This no doubt added to the sensation of a cooldown for those watching the eclipse outdoors, since a given temperature will typically feel warmer with the sun on your skin as opposed to when you’re in the shade. The drop in solar radiation also had a hefty impact on solar energy production across much of the country. In fact, utilities in California used it as a successful test case for how well the interconnected energy grid could make up for the predictable but significant loss in production.

|

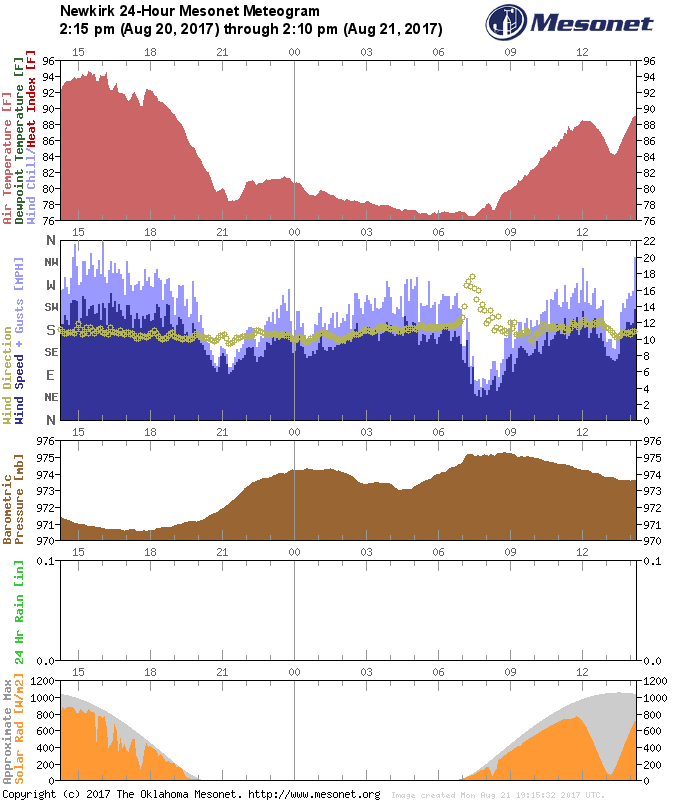

| Figure 2. This trace of conditions from the Oklahoma Mesonet site at Newkirk, OK (around 90% totality) shows the impact of the midday eclipse, with a temperature drop from around 88°F to 84°F just after noon on Monday, August 21 (top panel, far right side of graphic). Solar radiation (bottom panel) dropped from more than 700 watts per square meter to less than 100. Image credit: Oklahoma Mesonet. Thanks to Steve Koch (National Severe Storms Laboratory) for flagging this example. |

Satellite imagery from various spots around the country showed cumulus clouds dissipating in a few areas as the eclipse neared its peak, presumably a function of the drop in surface heating. This video from Lyndon State College at Lyndonville, Vermont (courtesy Jason Shafer, LSC) for the period from 1701Z to 1844Z (1:01 to 2:44 pm EDT) shows cumulus clouds developing at midday, then decreasing markedly as the eclipse hit its peak of about 60% totality in early afternoon—a time of day when fair-weather summer cumulus would normally be increasing rather than decreasing. The CIMMS Satellite Blog has a GOES-16 animation showing this effect, as well as the slow recovery of the cumulus field a few hours later.

My Category 6 teammate, Dr. Jeff Masters, caught the eclipse from a vantage point near Franklin, Kentucky. "Before the eclipse, there was about 10% coverage of cumulus," he said. "I assured my fellow eclipse watchers that the cooling effect of the eclipse would be enough to cause those clouds to dissipate, and that was exactly what happened, beginning 20 minutes before totality, with the cumulus field entirely gone 5 minutes before totality."

Notice how the cumulus clouds diminish during the #eclipse and take almost an hour after totality to redevelop! (goes16 prelim&non-op) pic.twitter.com/yPhCnZmHbW

— NWS Columbia (@NWSColumbia) August 22, 2017

Modeling the weather impacts of the eclipse

One of the most detailed efforts anywhere to model the weather impacts of the eclipse took place at NOAA/ESRL Global Systems Division and the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences. NOAA/CIRES scientists used an algorithm developed at the University of Barcelona to incorporate the amount of solar obscuration and solar-radiation decrease. The algorithm was implemented in a GSD version of NOAA's HRRR model (HRRRx). The model called for temperature drops of 3-7°C (5-12°F) within the umbra (the region of full shadow/totality) and up to 4°C (7°F) in the surrounding penumbra (the region of partial eclipse).

|

| Figure 3. This model depiction of solar radiation reaching ground level is part of an animation created in advance to simulate the effects of the 2017 eclipse on a typical summer day, using weather data from August 4, 2017. The dramatic eclipse-generated drop in radiation is strongest (dark blue) in and near the area of totality, which was near Kansas City at this point in the model run. Other areas of radiation loss related to model-generated clouds and storms rather than the eclipse can be seen elsewhere, including the area around Lake Michigan. Image credit: NOAA. |

“We were happy to see that our eclipse code worked exactly as hoped for," said GSD senior researcher Dr. Stan Benjamin. “A preliminary look shows the HRRRx with the eclipse code gave much better forecasts than any other weather model of 2-meter temperature across the US yesterday, compared with observations. It accurately accounted for the huge drop in solar radiation."

Now it’s your turn

Did you detect a temperature drop during the eclipse from your WU PWS? We’d love to see the temperature trace—please feel free to post it in the comments section below. Eclipse photos, anecdotes, etc., are also more than welcome!

Get your WU gear while it lasts!

Attention WU and WUTV fans: here is your chance to pick up WU-branded merchandise at a sweet discount. The online WU Store will be closing its virtual doors on August 31, but until then, you can get 40% off all merchandise, including T-shirts, hoodies camping mugs, and more. Just use the code WUTEAM40 when you're prompted, and the price will be adjusted before your order is finalized.