| Above: Infrared satellite image of Tropical Storm Ophelia at 11:45 am CDT Tuesday, October 10, 2017. Image credit: NOAA/NESDIS. |

Tropical Storm Ophelia appears to have its sights set on becoming the tenth consecutive hurricane of this year’s Atlantic season. As of 11 am EDT Tuesday, Ophelia’s top sustained winds were 50 mph. Fortunately, Ophelia is in the middle of the North Atlantic, far from land and about 780 miles west-southwest of the Azores.

Ophelia was looking much more symmetric in satellite imagery on Tuesday morning, after days of strong shear that gave Ophelia’s showers and thunderstorms (convection) a lopsided structure. The convection was not particularly strong, which fits with the “cold” environment surrounding Ophelia. Sea surface temperatures are barely warm enough for development—only 26-27°C, or 79-81°F. However, this is substantially above average for the time of year (1-2°C), and the upper atmosphere is unusually cold, so the combination of the two is boosting instability.

Outlook for Ophelia

Computer models have come into very strong agreement that Ophelia will soon be a hurricane. Nearly all of the 70 ensemble members of the GFS and European model runs from 00Z Tuesday bring Ophelia to hurricane strength, as do the 12Z Tuesday SHIPS model and the 06Z Tuesday runs of the HWRF and HMON intensity models. Wind shear over Ophelia has dropped into the light to moderate range (around 10 knots), and SHIPS now predicts that shear will remain mostly below 15 knots through Saturday. The atmosphere around Ophelia will remain on the dry side (mid-level relative humidity around 50%), so periods of dry-air intrusion could chip away at Ophelia’s intensity. In its 11 am EDT Tuesday advisory, NHC predicted that Ophelia would become a hurricane by Thursday morning.

Light steering currents are expected to keep Ophelia drifting southeast for the next day or two, before stronger upper-level westerlies kick in. By Saturday, Ophelia is likely to be accelerating east-northeast just south of the Azores; although a direct hit appears unlikely, it’s too soon to rule out that possibility. In NOAA’s historical hurricane database, which extends back to 1851, only 11 hurricanes have passed within about 200 miles of the Azores (as noted by weather.com). Every one of those occurred in August or September—except for strikingly unseasonal Hurricane Alex, which struck the islands in January 2016 just after weakening to tropical-storm strength.

Looking further ahead, NHC is predicting Ophelia to transition into a post-tropical cyclone with hurricane-force winds by Saturday as it continues racing east-northeast toward the Iberian Peninsula. Only two storms are known to have struck the west coast of Portugal or Spain as tropical cyclones: a transitioning hurricane in October 1842 and Hurricane Vince (as a tropical depression) in October 2005. Intriguingly, phase-space diagrams from Florida State University based on the 06Z Tuesday run of the GFS model suggest that Ophelia might actually approach the Iberian Peninsula as a weakening warm-core tropical cyclone—i.e., a tropical storm.

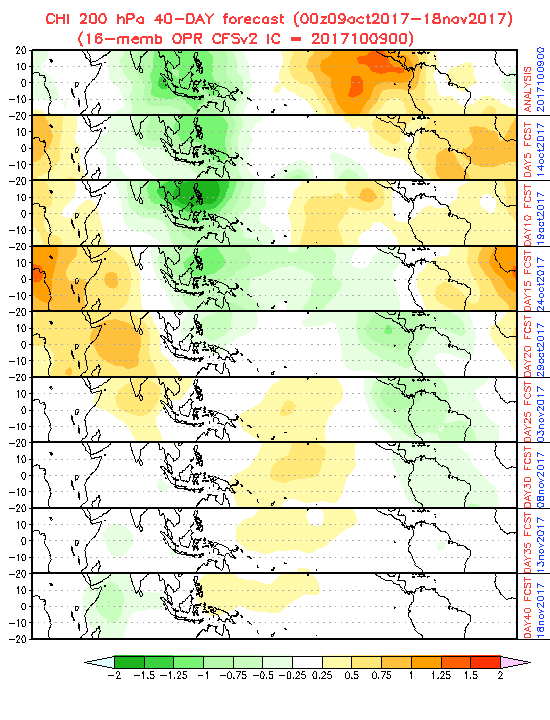

Ensemble models show a slight chance of Atlantic development this week in two areas of disturbed weather, one north of the Leeward Islands and the other in the central tropical Atlantic. Given the unfavorable state of the Madden-Julian Oscillation (see below), development of either disturbance appears quite unlikely, and neither was highlighted in the tropical weather outlook issued by NOAA at 8 AM EDT Tuesday.

|

| Figure 1. Visible GOES-16 satellite image at 11:45 am EDT Tuesday, October 10, 2017, showing Tropical Storm Ophelia (top right), a large area of disturbed weather east of the Bahamas (top left), and another sizable disturbance in the central tropical Atlantic (lower right). Image credit: RAMMB/CIRA@CSU. |

|

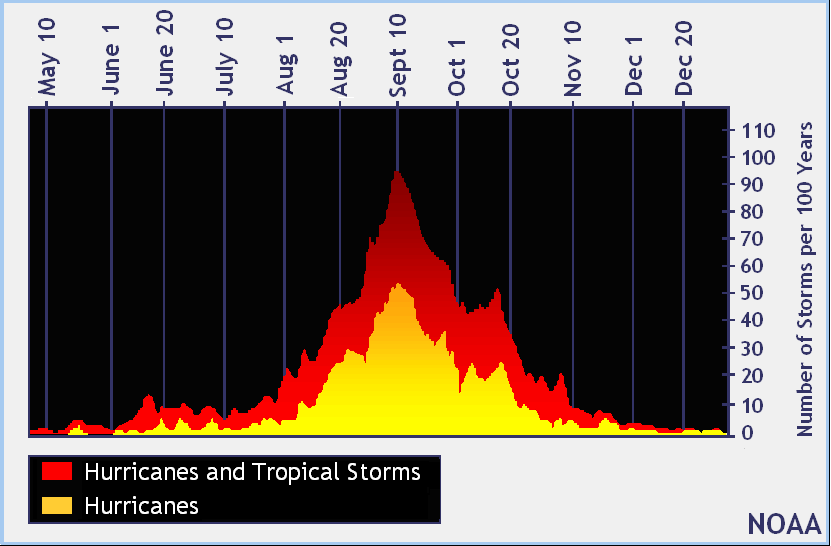

| Figure 2. Distribution across the calendar of named storms and hurricanes one would expect in a 100-year period across the Atlantic. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/NHC. |

Quiet spell ahead in the Atlantic?

Hurricane season in the Atlantic usually begins to wind down after mid-October, if not sooner. Based on 1971-2009 data, the average formation date of the year’s final hurricane is on October 15, and we would typically expect just one more named storm after that point. Although most of the tropical Atlantic remains unusually warm for mid-October, we may see a dropoff in tropical cyclone activity over the next couple of weeks, as the Madden-Julian Oscillation is predicted to enter a phase unfavorable for tropical development in the Atlantic. Instead, the MJO will favor rising motion and typhoon formation in the Northwest Pacific, a region that’s been oddly free of tropical cyclones during the last few weeks. The last named storm in the Northwest Pacific was more than three weeks ago; this marks the first time on record the basin was free of named storms between September 19 and October 9, according to Phil Klotzbach (Colorado State University). Long-range models suggest the possibility of one tropical cyclone forming in the South China Sea toward this weekend and perhaps another east of the Philippines next week.

|

| Figure 3. 40-day forecast of areas of rising and sinking motion at the 200-mb level (about 39,000 feet), based on the 00Z Monday run of the NOAA Climate Forecast System, version 2. These forecasts incorporate the predicted state of the Madden-Julian Oscillation, a slow-moving disturbance that propagates across the global tropics every 40 to 60 days. Areas in yellow and red denote sinking air and suppressed conditions for tropical cyclone formation; areas in green denote rising air and favorable conditions for tropical development. Based on this outlook, activity may be suppressed in the Atlantic until late October and early November. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPC. |

|

| Figure 4. Jim Stites watches part of his neighborhood burn in Fountaingrove, Calif., just north of Santa Rosa, on Monday, Oct. 9, 2017. Image credit: Kent Porter/The Press Democrat via AP. |

Wildfire disaster continues in California

At least 12 people were killed by the monstrous series of wildfires that erupted in and near California’s wine country, north of the San Francisco Bay area, from late Sunday night into Monday. At least 150 people remained missing as of Tuesday morning, according to SFGate.com, and an estimated 1500 structures have been lost. The hot, dry winds that fanned the fires had mostly subsided on Tuesday, although some of the fires continued to expand. See our Monday evening post for more details on the meteorology behind the firestorm. We’ll have more on this ongoing disaster in a forthcoming post.