| Above: A bridge is out as floodwaters rise in Provincia de Puntarenas, Costa Rica, on Thursday, October 5, 2017. Image credit: Instagram/@timeless_turmeric_ |

Tropical Depression 17 has become the 15th named storm of this exceptionally active Atlantic hurricane season. As of 11 am EDT Monday, newborn Tropical Storm Ophelia had sustained winds of 40 mph, according to the NOAA/NWS National Hurricane Center. Ophelia is located in the remote Central Atlantic, about 860 miles west-southwest of the Azores, and weak steering currents will keep it safely in this area for the next several days.

Like many late-season systems, Ophelia developed from the lingering remains of a decaying front that pushed across the North Atlantic. Strong wind shear slowed down Ophelia’s organization, shunting its showers and thunderstorms (convection) mostly northeast of a distinct low-level center of circulation. Since Sunday, though, convection has gradually increased and persisted closer to Ophelia’s center, and some banding has developed on its east side.

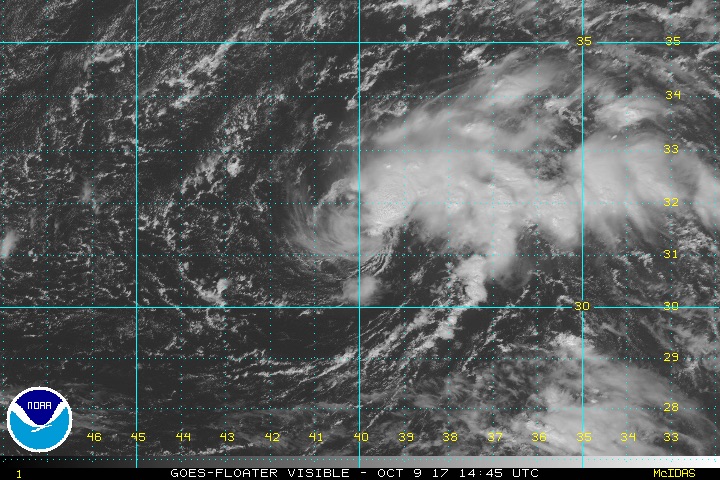

|

| Figure 1. Visible satellite image of Tropical Storm Ophelia at 10:45 am EDT Monday, October 9, 2017. Image credit: NOAA/NESDIS. |

Ophelia is making the most of a lukewarm environment for classic tropical cyclone development. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are marginal, around 27°C (81°F, or about 2°F above average for this time of year), with negligible oceanic heat content, and the atmosphere is not especially moist (mid-level relative humidity around 55%). However, temperatures are unusually cold at upper levels, and this is boosting atmospheric instability, helping to compensate for the tepid SSTs. Moreover, Ophelia appears to be tucked into a location with less wind shear than the overall surrounding environment. The 12Z Monday run of the SHIPS model indicates that large-scale wind shear will decrease from its current 25 knots to around 15 knots by Wednesday, as a zone of upper-level westerlies shifts south of Ophelia. The 6Z Monday runs of two of our top intensity models, the HWRF and HMON, bring Ophelia to hurricane strength by Friday. Our top global track models, which are less reliable for intensity forecasts, are less keen on Ophelia: none of the 20 members of the GFS ensemble run from 0Z Monday, and only 3 of the 50 members of the European ensemble, bring Ophelia to hurricane strength. This seems a good time to go with the intensity-tailored models, and NHC is doing just that, predicting that Ophelia will become a hurricane by Friday. If so, it will be the Atlantic’s tenth consecutive tropical storm to become a hurricane, matching a record set in 1878, 1886, and 1893.

After a midweek relaxation of steering currents around Ophelia, a stronger midlatitude trough is expected to begin carting the storm east or northeast. The GFS and ECMWF operational runs from 0Z Monday suggest that Ophelia could threaten the Azores this weekend.

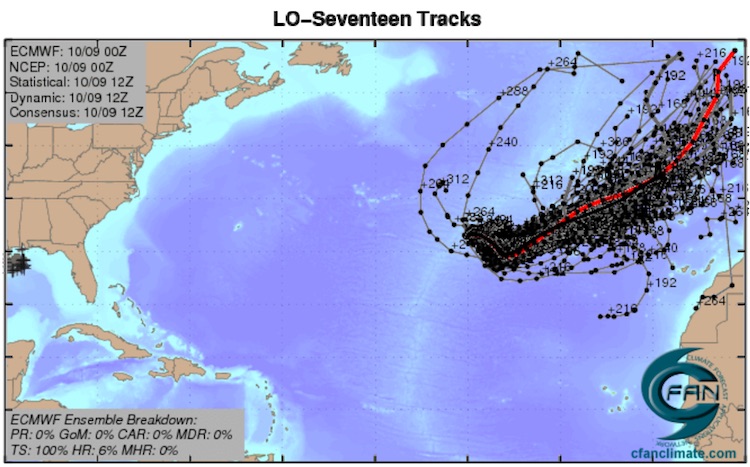

|

| Figure 2. The 0Z October 9, 2017 track forecast by the operational European model for Ophelia (red line, adjusted by CFAN using a proprietary technique that accounts for storm movement since 0Z), along with the track of the average of the 50 members of the European model ensemble (heavy black line), and the 50 track forecasts from the 0Z Monday European model ensemble forecast (grey lines). Image credit: CFAN. |

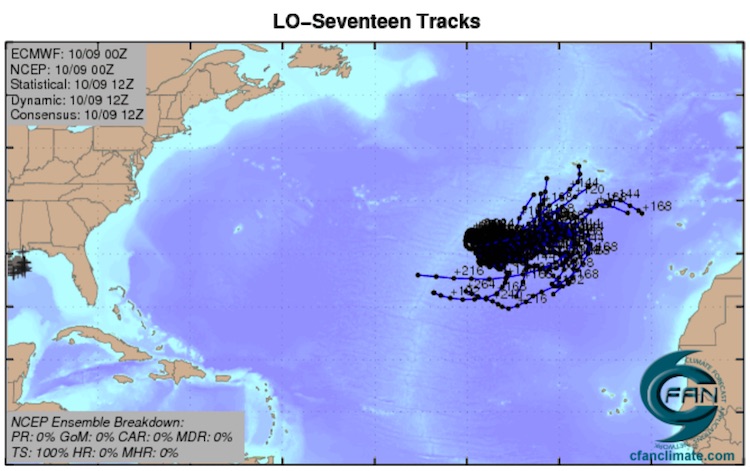

|

| Figure 3. The 20 track forecasts for Ophelia from the 0Z Monday, October 9, 2017 GFS model ensemble forecast. Image credit: CFAN. |

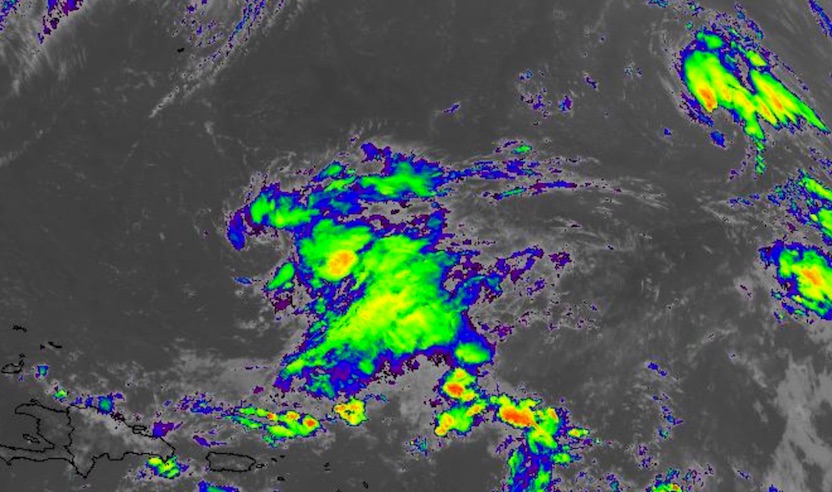

|

| Figure 4. Infrared GOES-16 satellite image of the area of disturbed weather east of the Bahamas and north of the Leeward Islands at 11:15 am EDT Monday, October 9, 2017. Tropical Storm Ophelia can be seen at top right. Image credit: NASA/MSFC Earth Science Branch. |

Watching for possible development east of the Bahamas later this week

The same frontal zone that gave birth to Ophelia extends to the area north of the Leeward Islands, where a weak upper low is spawning scattered convection. There are model indications that a tropical cyclone could form in this area and move west-northwest toward the Bahamas later this week. A few ensemble members from both the GFS and Euro models develop this system into a tropical depression or tropical storm by midweek. This disturbance is not yet highlighted in NHC’s Tropical Weather Outlook, but we give it a 20% chance of development into at least a depression by Friday. Large-scale steering will bring the system toward Florida by the weekend. Even if it does not fully develop, this disturbance could dump several inches of rain on parts of Florida. The next name on the list of Atlantic storms is Philippe.

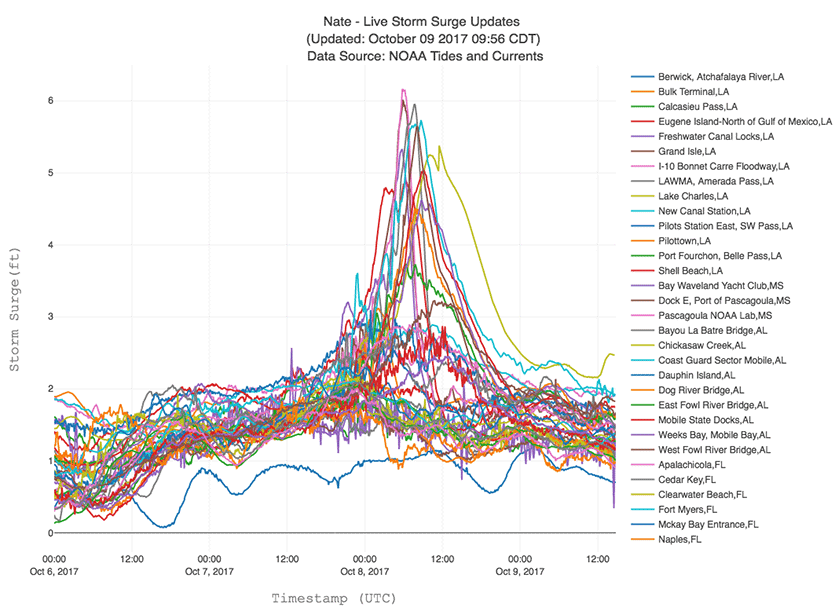

Picking up the pieces after Nate

Now classified as a post-tropical cyclone in northwest Pennsylvania as of midday Monday, the remnants of former Hurricane Nate were bringing heavy rains to the Northeast U.S. after the storm made a double landfall on Friday night and Saturday morning as a Category 1 hurricane with 85 mph winds. Nate’s initial landfall occurred in Louisiana at the mouth of the Mississippi River on Friday night, with the second landfall coming a few hours later on the coast of Mississippi. Nate brought a peak storm surge of 6.3’ to Pascagoula, Mississippi, and storm surge flooding inundated much of the Alabama coast, including Dauphin Island. In Mobile Bay, Alabama, the Coast Guard Station recorded water levels of 5.5’ above high tide, and water levels reached 5.8’ above high tide at Bayou La Batre. In Louisiana, the highest water level was just over 4.5’ at Shell Beach.

|

| Figure 5. Lanny Dean, from Tulsa, Oklahoma, takes video as he wades along a flooded Beach Boulevard next to Harrah’s Casino as the eye of Hurricane Nate pushes ashore in Biloxi, Miss., early on Sunday morning, Oct. 8, 2017. Image credit: Mark Wallheiser/Getty Images. Along with the embedded video below, Mike Theiss posted a dramatic video on Twitter showing him standing amid waist-high surge pouring into a casino parking lot. It should be emphasized that water in motion is extremely dangerous. NWS stresses: “A mere 6 inches of fast-moving flood water can knock over an adult. It takes just 12 inches of rushing water to carry away a small car, while 2 feet of rushing water can carry away most vehicles.” |

#StormSurge coming inside entrance of Golden Nugget casino in Biloxi #HurricaneNate pic.twitter.com/Sv0wwIbjWu

— Mike Theiss (@MikeTheiss) October 8, 2017

|

| Figure 6. Nate’s storm surge levels for the period ending at 10 am CDT Monday, October 9, 2017, from NOAA tide gauges in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and the Florida Panhandle. The highest storm surge was 6.3’ at Pascagoula, Mississippi. Other tide gauges in the region reported maximum storm surge levels of 4 - 6 feet, including Shell Beach, Louisiana; Bay Waveland Yacht Club, Mississippi; and Mobile State Docks along the Mobile, Alabama, waterfront. Image credit: SURGEDAT, the Southern Regional Climate Center (www.srcc.lsu.edu), and NOAA Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (www.southernclimate.org). |

According to the weather.com summary article on Nate, here are some peak wind gust reports in the U.S.:

- Calvert, Alabama: 75 mph

- Pascagoula, Mississippi: 70 mph

- Mobile, Alabama: 66 mph

- Destin, Florida: 58 mph

- Gulfport, Mississippi: 52 mph

As of midday Monday, the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center had logged 21 preliminary tornado reports from Nate, including12 in South Carolina, 5 in North Carolina, and 2 in Alabama. Among some of the notable wind damage or power outages reports:

- Clay County, Alabama: Numerous trees down blocking roads, numerous power outages in northern and western parts of the county

- Highlands, North Carolina: Numerous power outages

- Tallapoosa, Georgia: One injured from a large tree downed on a building

Here are some selected high rainfall totals from Nate:

- 11.62 inches in Great Falls, North Carolina

- 11.17 inches in Bear Creek, North Carolina

- 10.48 inches in Hogback, North Carolina

- 9.37 inches in Highlands, North Carolina

- 8.32 inches in Crestview, Florida

- 6.99 inches in Milton, Florida

- 6.95 inches in Slidell, Louisiana

- 6.94 inches in Dixon, Alabama

- 6.54 inches in Foley, Alabama

- 6.12 inches near Greenville, Kentucky

- 5.48 inches at Anna Ruby Falls, Georgia

|

| Figure 7. Observed 2-day rainfall amounts from Hurricane Nate through 9 pm EDT Sunday, October 8, 2017. Additional rains extended into the Northeast U.S. on Sunday night and Monday. Image credit: NWS. |

Nate’s toll in Central America

Hurricane Nate may not have left enough U.S. damage for the United States to request retirement of Nate’s name from the list of Atlantic storms. However, Nate’s impact on Central America, where 30 deaths are being blamed on the storm, 15 of them in Nicaragua, could well lead to its retirement. Costa Rica President Luis Guillermo Solís on Saturday called Nate’s aftermath the greatest crisis in the country’s history, after flooding from 12 hours of torrential rain on Wednesday killed 11, left 11,000 homeless, severely damaged the nation’s road system, and knocked out water to 447,000 people—about 9% of the nation’s population. “The magnitude of the damage caused by Tropical Storm Nate in the entire road infrastructure of the country is of titanic proportions,” said German Valverde, describing the condition of the national road network. The embedded tweet below includes this comment from Solís (as translated by Bing): “Protect yourself and protect your family! We do our work of care and protection for citizens and communities.”

¡Protéjase y proteja a su familia! Nosotros hacemos nuestro trabajo de atención y protección a ciudadanía y comunidades (Fotos: Filadelfia) pic.twitter.com/EUO8MoDvHs

— Luis Guillermo Solís (@luisguillermosr) October 5, 2017

Costa Rica hurricane history

Government officials said the damage from Nate is comparable to that of Hurricane Otto of 2016, the only hurricane on record ever to pass over Costa Rica. Otto killed 10 people and did $190 million in damage to the country. According to EM-DAT, the international disaster database, the deadliest and most destructive tropical cyclone in Costa Rica’s history was Hurricane Cesar, which made landfall in Nicaragua just north of Costa Rica on July 28, 1996, as a Category 1 storm with 75 mph winds. Cesar crossed over Central America and later became Category 4 Hurricane Douglas in the Eastern Pacific. Cesar/Douglas’s heavy rains caused flooding that killed 51 and did $200 million (1996 dollars) in damage to Costa Rica.

All-time warmest October lows in D.C. area on Sunday

Nate’s trek north helped reinforce a very warm, moist air mass in place east of the Appalachians. Summerlike dew points in the 70s led to unusually muggy conditions for early October. The low temperature on Sunday at Washington’s Reagan National Airport was 75°F. In records dating back to 1874, that was the city’s warmest daily minimum ever recorded in October, breaking the 74°F record set on October 4 and 5, 1898, and October 4, 1941. Capital Weather Gang reported that the mid-70s dew points were virtually unprecedented for this late in the autumn. All-time warm daily lows for October were also set at Washington’s Dulles Airport (73°F) and Philadelphia (74°F). Conditions in D.C. on Sunday were so oppressive that the annual Army Ten-Miler Road Race was cut short and recast as a “recreational run,” according to Stars and Stripes.

We’ll be back later today with an update on major fires that erupted north of the San Francisco Bay area on Sunday night. Critical fire weather conditions were shifting into the Los Angeles area on Monday, with strong Santa Ana winds expected.

Jeff Masters co-wrote this post.