| Above: Toxic clouds of particulate matter and sulfur dioxide gas spread over the Leilani Estates neighborhood from the eruption of Kilauea volcano on Hawaii's Big Island on May 6, 2018 in Pahoa, Hawaii. The volcano has spewed lava and high levels of sulfur dioxide gas into communities, leading officials to order 1,700 to evacuate. Officials have confirmed 26 homes have now been destroyed by lava in Leilani Estates. Image credit: Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images. |

As lava from last week’s eruption on the east flank of Hawaii’s Mt. Kilauea continues to engulf homes in slow motion—a total of 35 structures and at least one Ford Mustang had been lost as of Monday morning, May 7—it’s easy to see why the spectacular lava has dominated discussion of the hazards of this active volcano. The air close to an eruption can be dangerous in its own right, though.

| Video 1. On Sunday, May 6, 2018, Mick Kalber took these amazing aerial shots of the volcanic fissure sending lava through the streets of the Leilani Estates subdivision of far southeast Hawaii. Video credit: Courtesy Paradise Helicopters, used with permission. |

|

| Figure 1. A lava flow moves on Makamae Street after the eruption of Hawaii's Kilauea volcano on Sunday, May 6, 2018 in the Leilani Estates subdivision near Pahoa, Hawaii. The governor of Hawaii has declared a local state of emergency near the Mount Kilauea volcano after it erupted following a 5.0-magnitude earthquake, forcing the evacuation of nearly 1,700 residents. A 6.9-magnitude quake soon followed. Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey via Getty Images. |

The main culprit: Sulfur dioxide

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issues regulations for six air pollutants deemed to be the most dangerous for human health. These “criteria” pollutants are carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particulate matter (10µm or less and 2.5µm or less), as well as sulfur dioxide. Of the six, only particulate matter less than 2.5µm (PM2.5) and ozone have been linked to the estimated 105,000 premature air pollution deaths that occur each year in the U.S. However, high levels of sulfur dioxide have been linked to the deadliest air pollution disaster on record--the London, England smog episode of 1952. This disaster is now thought to have killed up to 12,000 people.

Episodes of high sulfur dioxide levels in Hawaii occur mainly near and downwind from the eruptive vents atop Kilauea. On a typical day, the volcano emits more than 100 tons of sulfur dioxide, sometimes more than 1000 tons. As SO2 reacts with other atmospheric components over a period of days, it can lead to hazy conditions called vog (a portmanteau of the terms smog, volcano, and fog).

Vog episodes are most common along Hawaii’s west coast, typically when air from around Kilauea sweeps around the south side of the island on trade winds and then gets pulled onshore during the day as the slopes of the Big Island’s volcanoes heat up and air is drawn onshore. Vog is less common in Hilo, on Hawaii’s east coast, but because of the city’s close proximity to Kilauea, the vog may be more concentrated when it occurs there, sometimes reducing visibility below 2 miles.

Vog can include elevated levels of PM2.5 in addition to SO2-derived sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Over time, the sulfur compounds interact with ammonia naturally present in the atmosphere to form ammonium sulfate, which can be the predominant problem when vog from Kilauea reaches Hawaii’s other islands.

The previous major eruption of Kilauea, in 2008, caused significant health effects in the local population due to high levels of SO2. People without respiratory disease reported upper respiratory symptoms, irritability, low energy levels, body aches, sleep disturbances, headaches and chronic throat irritation accompanied by a persistent cough that lasted for weeks. People with pre-existing lung problems reported far worse impacts, with a sixfold increase in hospitalization for those exposed to the high pollution.

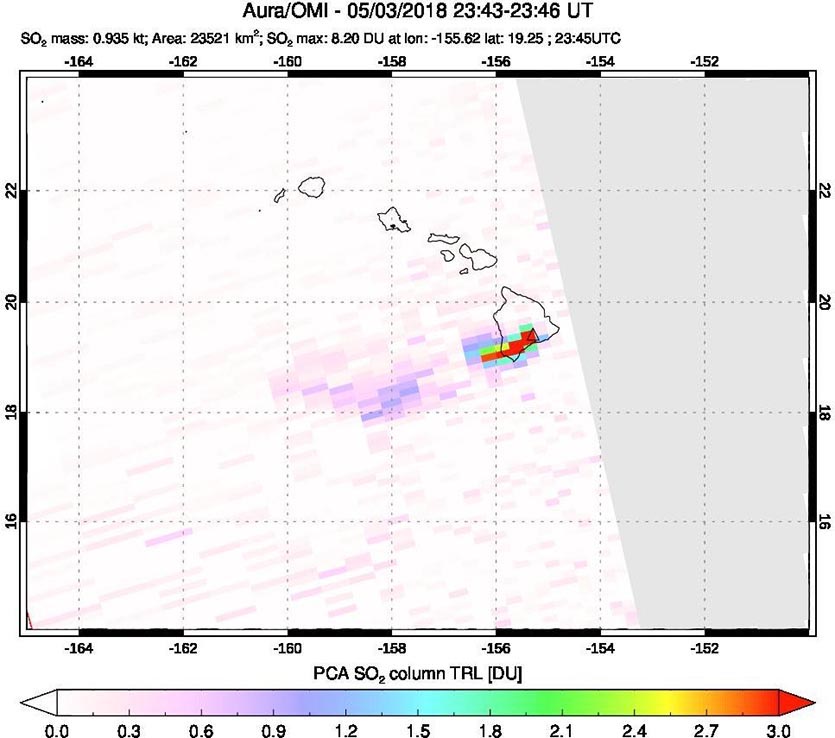

High SO2 levels from the past week’s eruptions of Kilauea have not been widespread, fortunately. Of the seven SO2 monitors on the Big Island, only the two located in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park had recorded levels of SO2 reaching the “orange” alert level—Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups—as of May 7. This occurred on the night of May 2-3 at the Jaggar Museum, which overlooks the Halema'uma'u crater on Kilauea, and on the afternoon of May 4 at the park’s visitor center.

|

| Figure 2. Enhanced concentrations of sulfur dioxide gas over Hawaii’s Big Island, as measured between 1:30 and 2:00 pm local time on Thursday, May 3, 2018, by the Aura satellite. Northeast trade winds were pushing the gas plume toward the southwest. See the Forbes post by Marshall Shepherd for more details. Image credit: NASA. |

|

| Figure 3. A column of reddish-brown ash pours out of Mt. Kilauea on Friday, May 4, 2018, at 12:46 pm local time, shortly after a magnitude-6.9 earthquake—Hawaii’s strongest in more than 40 years—shook the Big Island. Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey via AP. |

When rain meets lava

In the predawn hours of February 1, 2018, photographer Sean King led a group of three tourists across the vast lava fields below Hawaii’s Mt. Kilauea. The group was angling for a spectacular nighttime view of pockets of fresh lava oozing to the surface near the Chain of Craters Road in Volcanoes National Park. They were among dozens of visitors trekking across encrusted lava fields each day, either in organized groups or on their own—a practice allowed by the park under normal conditions.

Then it started to rain—bad news in more ways than one. The active lava sat amid a blanket of dried lava extending far in all directions. Rain and low visibility can obscure landmarks and make the hike to and from the active lava more treacherous. Another concern: rainfall hitting lava can generate very localized clouds of dangerous toxin-laden steam, formed by reactions between the water and the lava.

As clouds of steam enveloped the tour group, the tourists lost contact with King and eventually went to summon help. A helicopter rescue group found King later that morning, about four hours after he became separated from the tour group. King had died on the scene, apparently from the toxic fumes, although an official cause of death has not yet been announced. The tourists experienced only minor injuries.

This group was hiking on the former site of the Royal Gardens subdivision, a neighborhood engulfed by lava from a 1983 eruption. The last of the 75 homes in Royal Gardens was consumed in 2012. In a sign of 1960s optimism, Royal Gardens had been originally platted with 1500 residential lots.

|

| Figure 4. A cloud of toxic steam rises as lava reaches the Pacific Ocean in Volcanoes National Park on July 21, 2002. Tourists flocked to view a ramp-up in Kilauea’s lava flows following an eruption in May. Image credit: Phil Mislinski / Getty Images. |

Laze: More threatening than it sounds

Where lava flows into the sea, as it often does south of Kilauea, it can form an especially thick, dangerous whitish cloud nicknamed laze (lava and haze). Laze typically includes hydrochloric acid gas (HCl) and tiny particles of volcanic glass. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, laze can have the same corrosive properties as weak battery acid, with a pH value between 1.5 and 3.5.

A cloud of laze killed two people in 2000 who ventured near a point where lava was entering the Pacific. A paper called “Death by Volcanic Laze” in the journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine detailed the 2000 tragedy. Both of the victims, a 43-year-old man and a 42-year-old female, showed no signs of a deadly fall or injury, but both had extensive first- and second-degree burns where their skin was unprotected or covered by only one layer of clothing. Their deaths were attributed to pulmonary edema (swelling of the lungs) due to inhaling laze.

Hydrogen sulfide—renowned for its “rotten egg” smell—can also be a hazard near volcanoes. No deaths related to hydrogen sulfide have been reported in Hawaii, according to a 2014 study in the Hawai’I Journal of Medicine and Public Health. However, hydrogen sulfide has been implicated in several deadly volcano encounters in Indonesia.

Carbon dioxide, colorless and odorless, is an even more stealthy villain. More than 1700 people were killed in a bizarre 1986 incident when a burst of carbon dioxide escaped from a buildup of volcanic gases trapped beneath Lake Nyos in Cameroon.

Dr. Jeff Masters co-wrote this post.

|

| Figure 5. This composite panoramic photo of Cameroon's Lake Nyos was taken eight days after the limnic eruption that proved catastrophic for the region, killing more than 1700 people. Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey. |