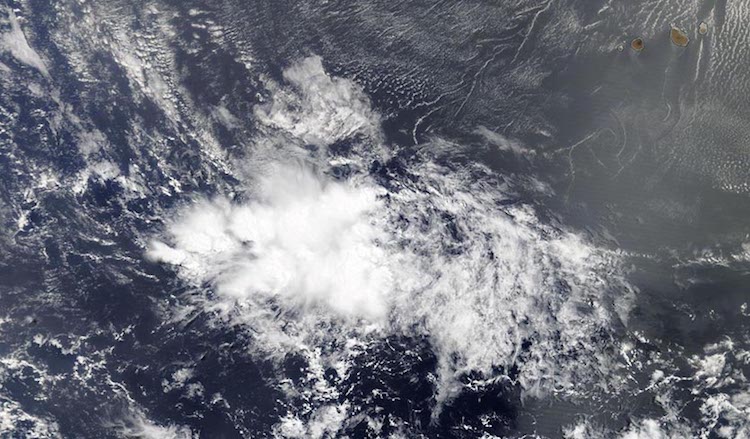

| Above: Enhanced infrared GOES-16 satellite image of the disturbance formerly known as TD 4, located northeast of Puerto Rico at 1645Z (12:45 pm EDT) Monday, July 10, 2017. GOES-16 data are preliminary and non-operational. Image credit: NASA/MSFC Earth Science Branch. |

A renewed burst of showers and thunderstorms (convection) developed early Monday around the remnants of Tropical Depression 4, located several hundred miles east of the Bahamas. This depression originated on Wednesday in the central tropical Atlantic with a sizable low-level circulation, but widespread dry air associated with the Saharan Air Layer torpedoed TD 4’s ability to generate convection and develop further. NHC terminated TD 4 on Friday, but it now appears possible that TD 4 may be springing back to life. Satellite loops of the system (which were reinitiated on Monday under the name 04L) illustrate the vivid burst of convection over the last few hours.

Michael Ventrice (The Weather Company) believes the new lease on life may be the result of 04L having moved north of 20°N latitude. Across the deep Atlantic tropics, he says, the system was being tamped down by the effects related to the suppressed phase of a convectively coupled Kelvin wave—a large, slow-moving atmospheric wave that can enhance or detract from hurricane formation in the deep tropics. Now that 04L is beyond the Kelvin wave’s direct influence, Ventrice believes it may have a better chance of strengthening.

It will take until this evening before computer models have fully incorporated the regrowth of 04L into their forecasts, but the European model from last night (0Z Monday) was already indicating some support for modest redevelopment. Most of the 50 members of the European ensemble run from 0Z Monday bring 04L to depression strength, and about a third of the ensembles produce a tropical storm, though only one of the 50 generates a hurricane. The ensemble is in close agreement on a westward track through the Bahamas in about 3-4 days, with much greater track divergence thereafter—solutions range from a track toward the Texas coast to an East Coast hugger that reaches Newfoundland!

Interestingly, only 2 of 20 GFS ensemble members take 04L to tropical storm strength, and even those dissipate 04L before it clears the Bahamas. The GFS tends to produce more hurricanes overall than the European model, so the discrepancy in this direction is a bit unusual. The last several runs of the UKMET model have not supported redevelopment of 04L in the Bahamas, although the model has favored at least some redevelopment into a tropical depression or tropical storm after 04L passes into the eastern Gulf of Mexico late this week. Tonight’s 0Z Tuesday model runs should be able to incorporate 04L’s growth spurt, so it will be interesting to see if the GFS comes on board. The 12Z Monday run of the SHIPS statistical model shows that 04L will continue to struggle with dry air (mid-level relative humidities of only around 50% for the next several days). However, wind shear will be gradually dropping from around 15 knots on Monday to less than 10 knots by Wednesday, and warm sea-surface temperatures of 28-29°C (82-84°F) would certainly support development. The Hurricane Hunters are now scheduled to investigate the system on Tuesday.

|

| Figure 1. A tropical wave located a few hundred miles southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands, as seen on Monday morning, July 10, 2017, by the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Terra satellite. Image credit: NASA. |

Next up: another wave in the eastern Atlantic

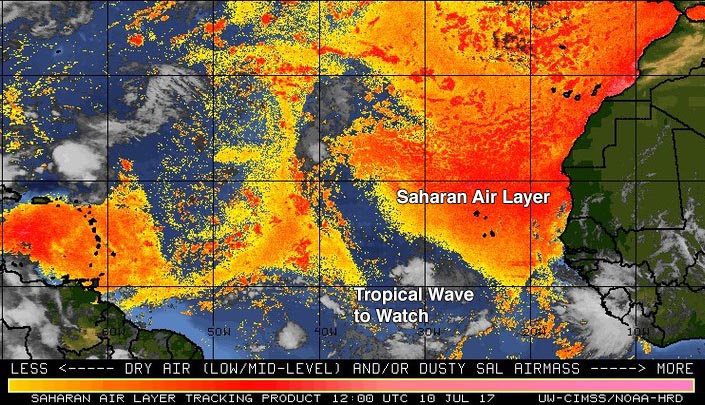

A tropical wave now chugging across the eastern tropical Atlantic at around 30°W longitude should be approaching the Lesser Antilles by week’s end, although its strength by that point—and its future beyond that point—are highly uncertain. NHC gives the wave a near-zero chance of development by Wednesday but a 20% chance of becoming at least a tropical depression by Saturday.

A huge zone of dry Sarahan air is lurking to the east and north of this wave (see Figure 2 below), but the dry air is somewhat less extensive and uniform ahead of the wave as it moves west at about 15 knots (17 mph). There is plenty of moisture associated with the wave itself, and wind shear is fairly low across the central tropical Atlantic apart from an upper trough extending into the tropics between 40° and 45°W. Sea surface temperatures of around 28°C (82°F) are close to 1°C above average and more than adequate for development.

|

| Figure 2. The Saharan Air Layer (SAL) analysis from 8 am EDT Monday, July 10, 2017, showed a large area of dry Saharan air off the coast of Africa, but a relatively moist atmosphere in the region of the tropical wave we are watching. Image credit: University of Wisconsin CIMSS/NOAA Hurricane Research Division. |

Of our three most reliable models for hurricane development, the operational European model does not develop this wave into a tropical cyclone, nor do any Euro ensemble members from 0Z Monday. Likewise, the UKMET model does not support development. In contrast, the operational GFS model has been remarkably consistent for several days in predicting a gradual strengthening of this wave, so that it approaches the Lesser Antilles as a tropical depression or tropical storm around Friday or Saturday. The GFS has also trended toward strengthening the system over the weekend in the eastern Caribbean—a region that is often hostile to development because of diverging low-level winds and sinking air. Beyond that point, the GFS operational and ensemble runs have offered a dizzying array of possible tracks and intensities, some involving the U.S. Gulf or Atlantic coasts. Any such coastal impacts are highly speculative, given the disagreement among models, and any U.S. effects from this wave would be well more than a week away—a time frame where forecast skill for tropical cyclone behavior is extremely small.

|

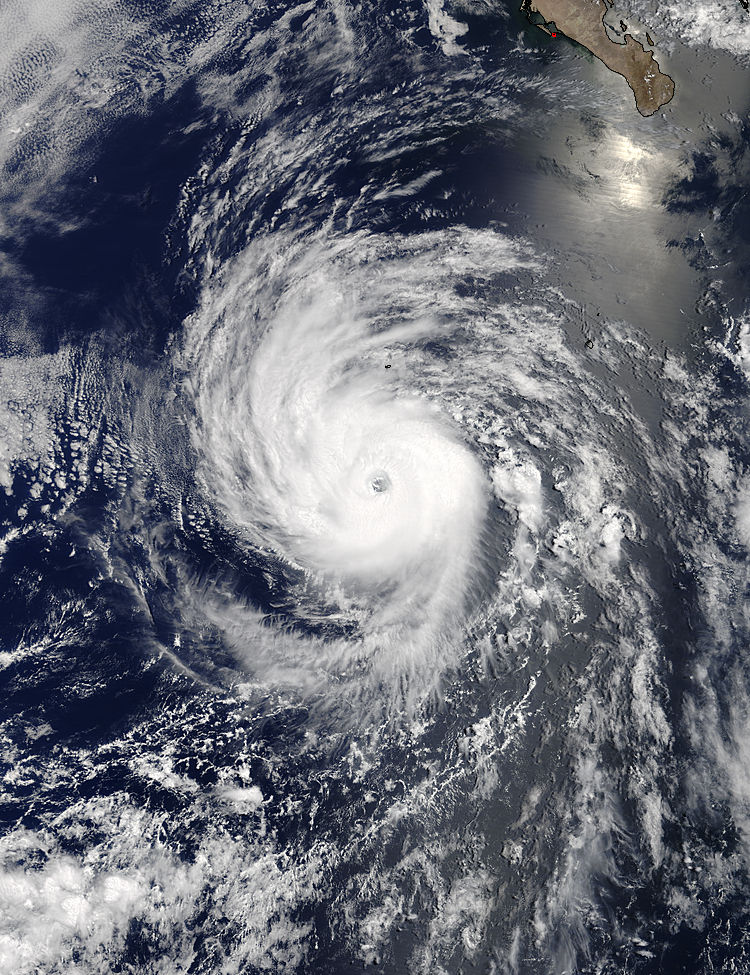

| Figure 3. Hurricane Eugene southwest of the tip of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula as seen by the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Terra satellite at 2:15 pm EDT Sunday, July 9, 2017. At the time, Eugene was at peak strength—a Category 3 hurricane with 115 mph winds. Image credit: NASA. |

Eugene weakening after becoming the Eastern Pacific’s first major hurricane of 2017

Hurricane Eugene peaked on Sunday afternoon as the Eastern Pacific’s first major hurricane of 2017, but is now weakening rapidly after encountering cooler ocean waters of 26°C (79°F) and a drier, more stable atmosphere about 550 miles west southwest of the tip of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. As of 11 AM EDT Monday, Eugene was a Category 1 storm with winds of 85 mph, well below its peak Category 3 status with 115 mph winds it attained on Sunday afternoon. Eugene was the year's first major hurricane in the Northern Hemisphere; the Atlantic has not yet had a hurricane, and the Northwest Pacific has been exceptionally quiet with no typhoons thus far in 2017. The last year to go this late without a major Northern Hemisphere hurricane was 1987, according to Phil Klotzbach (Colorado State University).

Eugene’s formation date of July 7 came two weeks before the usual July 22 date for the Eastern Pacific’s fifth named storm. Eugene became a major hurricane on July 9, about ten days earlier than the usual July 19 appearance of the basin’s first major hurricane. Eugene is the second hurricane of the Eastern Pacific’s season; we were exactly on schedule for the first Eastern Pacific hurricane of the year-- Hurricane Dora formed on June 26, which is the average date of the Eastern Pacific’s first hurricane formation.

It is unusual for both the Eastern Pacific and Atlantic to have above-average hurricane seasons, but that is exactly what has been occurring this year—so far . We’ve already had three named storms in the Atlantic: Arlene, Bret and Cindy. We came close to getting a fourth storm, Tropical Storm Don, when Tropical Depression Four formed last week. The fourth named Atlantic storm of the year doesn’t typically form until around Aug. 23, based on the 1966-2009 average. The first Atlantic hurricane of the year usually arrives by August 10.

Dr. Jeff Masters co-authored this post.