| Above: Search and Rescue personnel look for human remains in the Journey's End Mobile Home park following the damage caused by the Tubbs Fire on Oct. 13, 2017 in Santa Rosa, California. Image credit: Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images. |

The forecast is grim: Another round of dry, windy, fire-stoking weather is set to sweep across California from late Friday into the weekend. As of 10 am PDT Friday, fire weather conditions are predicted by the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center to be in the “critical” range (the second highest alert level) from Friday through Saturday across two areas: the hard-hit North San Francisco Bay region and the coastal mountain ranges and foothills north of the Los Angeles Basin. In SPC’s Day 2 outlook issued Friday afternoon, a new area of critical conditions was predicted for Saturday in the Colorado River valley near Las Vegas.

This weekend’s pattern appears nearly as dangerous as the one that pushed gale-force winds and parched air into California’s wine country late Sunday night, triggering a deadly swarm of fires—many of which were still less than 25% contained on Friday. As was the case on Sunday night, an upper-level trough sweeping through the western U.S. will push a strong surface high into the Great Basin. The flow around that high will force arid air westward, into and over the coastal ranges of California. As this already-dry air descends, it heats up through compression, and the relative humidity drops.

Winds could gust as high as 50-60 mph on higher terrain from late Friday into early Saturday across the North Bay Mountains, East Bay Hills, and the Diablo Range, and relative humidities as low as 10% are possible. The highest threat areas noted by NWS/San Francisco included the Napa County hills, the Mount Saint Helena area, the hills of eastern Sonoma County, and the hills of Marin County around Mount Tamalpais. Across the south slopes of the L.A. and Ventura County mountains, wind gusts are expected to peak in the 30-45-mph range from Saturday into early Sunday, with relative humidities dropping as low as 5%. Conditions should begin to improve in the North Bay late Saturday and over the L.A. region on Sunday.

|

| Figure 1. Fire weather outlooks for Friday and Saturday, October 13-14, 2017, issued by the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center at midday Friday. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/SPC. |

|

| Figure 2. A CalFire air tanker makes a drop on a wildfire at sunset as the pilot protects structures on the Hawkeye Ranch above Geyserville, Calif., Thursday Oct. 12, 2017. Since igniting Sunday in spots across eight counties, the fires have transformed many neighborhoods into wastelands. Image credit: Kent Porter/The Press Democrat via AP. |

Horrific statistics

The death toll from the North Bay fires had risen to 32 as of Friday, making the weeklong event the deadliest fire sequence in California history, and the toll is expected to rise as more victims are discovered. The previous record was held by the Griffith Fire in Los Angeles on October 3, 1933, which spread across just 47 acres of Griffith Park but killed at least 29 civilian firefighters. As of Friday, this week’s fires had scorched more than 212,000 acres. Although one victim was just 14, many of those killed this week were 70 or older, including a 98-year-old woman and her 100-year-old husband. Sonoma County Sheriff Robert Giordano said: “We have recovered people where their bodies are intact, and we have recovered people where there’s just ash and bone.”

The acreage burned this week isn’t yet a record: several other California fire events have covered more than 200,000 acres. However, the week's fires are the most destructive by far in state history, with an estimated 3500 structures lost as of Friday. The previous record-holder was the infamous Oakland Hills firestorm of October 1991, which consumed roughly 2900 structures.

|

| Figure 3. Top 20 most destructive wildfires in California history as of February 2017. Image credit: CalFire. |

|

| Figure 4. Smoke billows from a fire burning in the mountains over Napa Valley, Friday, Oct. 13, 2017, in Oakville, Calif. Firefighters gained some ground on a blaze burning in the heart of California's wine country but faced another tough period ahead on Friday and Saturday, with low humidity and high winds expected to return. Image credit: AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli. |

Human-driven climate change and development patterns are making destructive firestorms more likely

The preconditions for fast-spreading wildland fire are the same as they’ve always been: strong winds and hot, dry air moving through parched vegetation. However, much like floods, wildfires are shaped not just by the natural environment but also by how and where people live and work. Increasing numbers of Americans are living in or near regions known as the wildland-urban interface (WUI). These are typically scenic places where subdivisions have been built in or near forests, taking advantage of the natural beauty but putting people close to fire-prone areas that are difficult to keep safe. High wind can carry burning embers far ahead of a wildfire, quickly lighting up neighborhoods well away from a fire front (which was apparently the case in the hard-hit community of Santa Rosa in the predawn hours on Monday). The increased population in the wildland-urban interface also makes it more likely that human activity will lead to fire, either intentionally or inadvertently. At least some of the fires on Sunday night may have started because of power lines brought down in high wind.

Every U.S. state has at least some land that qualifies as WUI, based on criteria put forth by the National Fire Protection Association that include:

- amount, type, and distribution of vegetation

- flammability of the structures (homes, businesses, outbuildings, decks, fences)

- proximity to fire-prone vegetation and to other combustible structures

- weather patterns and general climate conditions

- topography

- hydrology

- average lot size

- road construction

|

| Figure 5. A stairwell smolders as a home burns during the Tubbs Fire on October 12, 2017 near Calistoga, California. Image credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images. |

Another factor raising the odds of destructive wildfire is human-produced greenhouse gases. As our climate warms, temperatures are rising especially quickly during droughts, where most of the sun’s heat can go into warming the land and air as opposed to evaporating moisture. California is a classic example of this phenomenon. Temperatures smashed countless records during the state’s vicious five-year drought that began in 2011. Droughts are not always unusually warm, but that's more and more becoming the case in our warming climate. In a 2015 study, Noah Diffenbaugh (Stanford University) and colleagues found that human-produced climate change had raised the odds that a drought year in California would also be an exceptionally warm year. The authors added: “A large ensemble of climate model realizations reveals that additional global warming over the next few decades is very likely to create ∼100% probability that any annual-scale dry period is also extremely warm.”

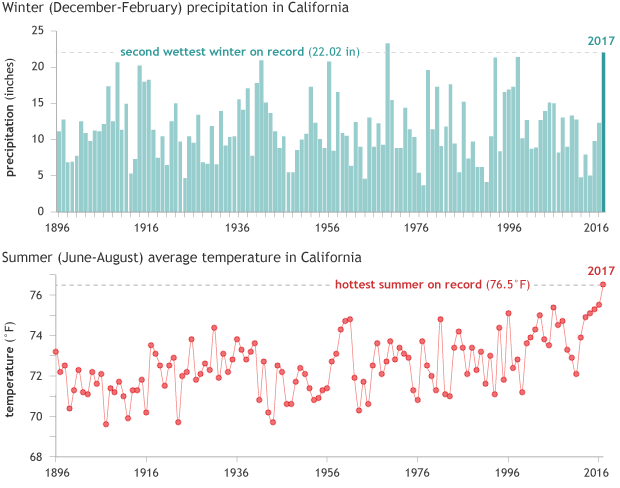

California’s drought ended in spectacular fashion in late 2016 and early 2017, when the state experienced its second-wettest winter on record. The moisture led to a mammoth burst of vegetation that promptly dried out in the summer. This is a normal happening in California’s Mediterranean climate (wet, mild winter and dry, hot summer), but in this case a very wet winter segued into the hottest summer on record. The first two weeks of September were also extremely hot. As NOAA’s Rebecca Lindsey put it in a climate.gov analysis this week: “Baked to tinder in the extreme heat, the abundant vegetation of spring became the kindling for these autumn fires.”

|

| Figure 6. Winter (December–February) precipitation (top) and summer (June–August) average temperature in California for the period 1896–2017, including the exceptional readings from winter 2016-17 and summer 2017. NOAA Climate.gov graphs, based on data from NCEI's Climate at a Glance tool. Image credit: climate.gov (NOAA). |

Climate Signals has a comprehensive roundup of factors related to climate change that are increasing wildfire risk in California.

Weeks to go before the California fire season ends

The immediate threat of critical fire weather will fade by Monday, but Californians may have a long way to go before they can put this grueling fire season behind them. Not counting the current, ongoing fire event, seven of the state’s 20 most destructive fires occurred in the month of October and four occurred in November, as shown in Figure 3 above. It will take significant rain to cut the risk that recurrent bouts of high wind and heat will cause new fires or exacerbate old ones. There are promising signs in the GFS forecast model that a wet storm will bring 0.5” to 1.0” of rain to the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas by next weekend, but the European model run from 12Z Friday showed a less-wet storm.

See our post from earlier Friday for more on Hurricane Ophelia, which will sweep near the Azores on Saturday as a hurricane and across or near Ireland as a powerful post-tropical storm on Monday. We'll have our next post no later than Sunday afternoon. Our thanks go to WU weather historian Christopher Burt for information and perspective on the California fires.