| Above: A man carries personal items through flooding associated with Hurricane Matthew on October 11, 2016, in Fair Bluff, North Carolina. Matthew, the Atlantic’s first Category 5 hurricane since 2007, left a trail of destruction from the Lesser Antilles to Virginia. Haiti was hardest hit, with more than 500 deaths and nearly $2 billion in damage. Image credit: Sean Rayford/Getty Images |

Odds have risen for an Atlantic hurricane season that should at least match the norms of recent years, according to the forecast updates issued by two leading seasonal prediction groups. In their June 1 outlook, issued on the first day of the Atlantic season, Dr. Phil Klotzbach and Dr. Michael Bell (Colorado State University) are now calling for 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) of 100. These numbers include Tropical Storm Arlene, which spun harmlessly in the open Atlantic as only the second tropical storm on record in the Atlantic for April.

The CSU team boosted the numbers in this June 1 update from its April 14 outlook, which had called for 11 named storms, 4 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 75. The two main reasons for the upgrade are:

—a reduced likelihood of a significant El Niño this year

—warming of the tropical Atlantic relative to the seasonal norm

To produce its June outlooks, CSU has examined a wide range of atmospheric and oceanic variables and zeroed in on the four that appear to be most closely related to Atlantic hurricane production. Two of those four elements suggest a busier-than-usual season this year, while the other two indicate a quieter-than-usual season, thus leading to the near-average outlook.

The closest analog years for 2017 identified by the CSU team are:

1957 (8 named storms, 3 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, ACE of 79)

1969 (18 named storms, 12 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes, ACE of 166)

1979 (9 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, ACE of 93)

2006 (10 named storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 major hurricane, ACE of 79)

These analog years have produced some landmark hurricanes, particularly in the Gulf of Mexico, including Audrey (1957), Camille (1969), and David and Frederic (1979; David remained east of the Gulf but affected eastern Florida). CSU emphasizes: “…these forecasts do not specifically predict where within the Atlantic basin these storms will strike. The probability of landfall for any one location along the coast is very low.” In its landfall probability estimates, CSU departs only slightly from the long-term average, calling for a 1% - 3% increase over the climatological odds of a hurricane making landfall for each state from Texas to North Carolina.

CSU’s June 1 outlooks are considerably more skillful than their April forecasts. When applied to the last 35 Atlantic seasons, the statistical technique used by CSU since 2011 for producing the June outlooks showed an 83% success rate in pegging whether a season will produce above- or below-average ACE. The average error for these “hindcasts” was 30 ACE units for the outlooks issued in June and 41 units for those issued in April, compared to the 52 units one would average per year by simply going with the climatological average.

Two big uncertainties: El Niño and Atlantic sea surface temperatures

One of the remaining question marks in the Atlantic hurricane outlook is whether El Niño will develop this year. El Niño tends to produce westerly upper-level winds that impede hurricane development in the Atlantic. The world’s leading models for ENSO prediction (El Niño-Southern Oscillation) continue to diverge in their El Niño outlooks for the remainder of 2017. This isn’t too shocking: ENSO forecasts are toughest during northern spring, when the El Niño region of the eastern tropical Pacific is often going through transition.

|

| Figure 1. Weekly sea surface temperatures over the past year in the Niño3.4 region of the eastern tropical Pacific. An El Niño is considered to be in place when SSTs average at least 0.5°C above the seasonal norm in the Niño3.4 region for five consecutive overlapping three-month periods. Image credit: NOAA. |

The consensus of global models still leans toward warm-neutral or weak El Niño conditions later this year, as reflected in a mid-May compilation from NOAA/IRI. However, NOAA/IRI are now calling for a 40-50% chance of El Niño in their May outlook, down slightly from the 50-55% chance in their April outlook. CSU is on the same wavelength: “Our confidence that a weak to moderate El Niño will develop has diminished since early April. While upper ocean content heat anomalies have slowly increased over the past several months, the transition towards warm ENSO conditions appears to have been delayed compared with earlier expectations. At this point, we believe that the most realistic scenario for the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season is borderline-warm neutral ENSO to weak El Niño conditions.”

A quirky SST pattern across the North Atlantic (Figure 2) is also throwing uncertainty into the outlook. Typically, warmer-than-average waters in the tropical Atlantic (which would favor a busy season) are associated with warmer-than-average SSTs in the far north Atlantic and off the U.S. East Coast. This May featured warmer-than-average SSTs in the latter two areas, but waters of the far north Atlantic were cooler than average. This suggests that other factors may be altering the usual relationship between these three regions.

Klotzbach and Bell summarized the remaining uncertainties: “If the tropical Atlantic were to remain warmer than normal and the odds of El Niño were to continue to diminish, additional increases in the seasonal forecast would be likely. However, if the tropical Atlantic were to anomalously cool and the tropical Pacific were to anomalously warm, the seasonal forecast could be decreased in our July and August updates.”

|

| Figure 2. Departure of sea surface temperature (SST) from average for May 2017, as computed by NOAA/ESRL. SSTs in the hurricane Main Development Region (MDR) between Africa and Central America were above average. Virtually all African tropical waves originate in the MDR, and these tropical waves account for 85% of all Atlantic major hurricanes and 60% of all named storms. When SSTs in the MDR are much above average during hurricane season, a very active season typically results (if there is no El Niño event present.) Conversely, when MDR SSTs are cooler than average, a below-average Atlantic hurricane season is more likely. Image credit: NOAA/ESRL, via CSU. |

TSR also predicts a near-average Atlantic hurricane season: 14 named storms

The May 26 forecast for the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season made by British private forecasting firm Tropical Storm Risk, Inc. (TSR) increased the predicted activity during the coming season, with forecast numbers close to the long-term (1950-2016) norm and the recent 2007-2016 ten-year norm. TSR is predicting 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 intense hurricanes and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 98 for the period May though December. The long-term averages for the past 65 years are 11 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 intense hurricanes and an ACE of 101. TSR rates their skill level as medium for these May forecasts—20% to 36% higher than a "no-skill" forecast made using climatology.

TSR predicts a 40% chance that U.S. landfalling activity will be above average, a 27% chance it will be near average, and a 33% chance it will be below average. They project that three named storms, with one of these being a hurricane, hitting the U.S. The averages from the 1950-2016 climatology are also three named storms and one hurricane. They rate their skill at making these May forecasts for U.S. landfalls just 3 - 5% higher than a "no-skill" forecast made using climatology. In the Lesser Antilles Islands of the Caribbean, TSR projects one named storm and no hurricanes. Climatology is one named storm and less than 0.5 hurricanes.

As we discussed in a post on May 25, there is some disagreement (per usual) among the various outlooks issued since April as to how busy a hurricane season the Atlantic will see. However, the outlooks issued more recently have tended to call for more activity than the earlier outlooks. The Barcelona Supercomputing Center and Colorado State University have a nice web page summarizing all of the major Atlantic hurricane season forecasts.

|

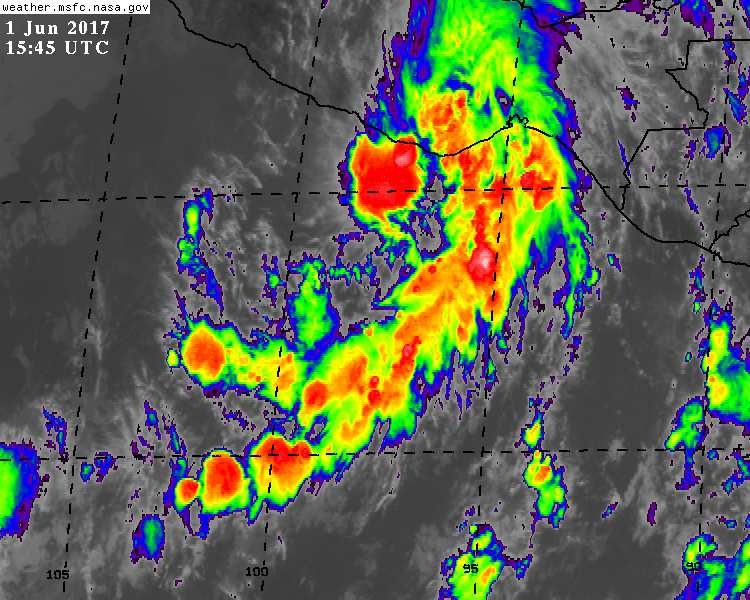

| Figure 3. Infrared satellite image of Tropical Depression 2E as of 1545Z (11:45 am EDT) Thursday, June 1, 2017. Image credit: NASA MSFC Earth Science Office. |

Heavy rains continue as TD 2E approaches Mexican coast

The window for Tropical Depression 2E to become a tropical storm was narrowing fast on Thursday morning. As of 11 am EDT, TD 2E was located about 45 miles west-southwest of Puerto Angel, Mexico, moving north-northeast at about 6 mph toward the Oaxacan coast. The National Hurricane Center pegged 2E’s sustained winds at 35 mph, although they note that satellite data supports an estimate of minimal tropical storm strength. Most of the showers and thunderstorms associated with 2E are located in a large band extending south from its center. This band should continue to funnel heavy rain toward the coast east of Puerto Angel even after 2E pushes ashore.

With 2E now on track to make landfall Thursday evening, it is very unlikely but not impossible that 2E will briefly become a named storm (in which case it would be Tropical Storm Beatriz). [Update: NHC upgraded 2E to Tropical Storm Beatriz at 2:00 pm EDT Thursday, as data from the ASCAT scatterometer showed a small area of 35-40 knot winds around the center of Beatriz. Top sustained winds at 2 pm EDT were set by NHC at 45 mph. No significant strengthening is expected before Beatriz makes landfall.]

Vertical wind shear remains fairly low over 2E, around 10 knots, but the 12Z Thursday run of the SHIPS model predicts that shear will ramp up to around 15 knots by Thursday night. The environment around TD 2E will be drying slightly as well, with mid-level relative humidities predicted to drop from near 80% to around 70% by Friday.

Puerto Angel had already received more than 6” of rain by Thursday morning, according to NHC, and widespread 8” – 12” totals can be expected across Oaxaca. Up to 20” is possible in favored areas, such as south-facing mountainsides east of 2E’s track. Floods and mudslides remain a distinct threat: a slow-moving tropical depression can produce just as much hydrologic trouble as a tropical storm.

Jeff Masters co-authored this post.