| Above: Thomas Saffel shovels snow off a small roof in Laramie, Wyo., on Thursday, May 18, 2017. A late-spring snowstorm returned much of the Wyoming landscape to more of a winter scene while hampering travel. Wyoming experienced its wettest November-to-April period on record. Image credit: Shannon Broderick/Laramie Daily Boomerang via AP. |

The generous moisture that graced much of the western U.S. this winter is not only replenishing water supplies but also helping to tamp down wildfire risk. Most of the West can expect average or below-average wildfire potential throughout the summer, according to the seasonal outlook issued on May 1 by the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). However, grassland and brush fire may become an increasing threat over parts of the West by late summer. Fire risk was projected to continue high across drought-stricken parts of southern Georgia and Florida, with little improvement until at least June or July (though rains this week may help).

|

| Figure 1. A Florida Forest Service worker, background right, positions a water truck behind a burning stand of brush as the Anclote Branch fire continues to burn Monday, May 8, 2017, in the Starkey Wilderness Preserve in Florida's Pasco County. Image credit: Douglas R. Clifford/The Tampa Bay Times via AP. |

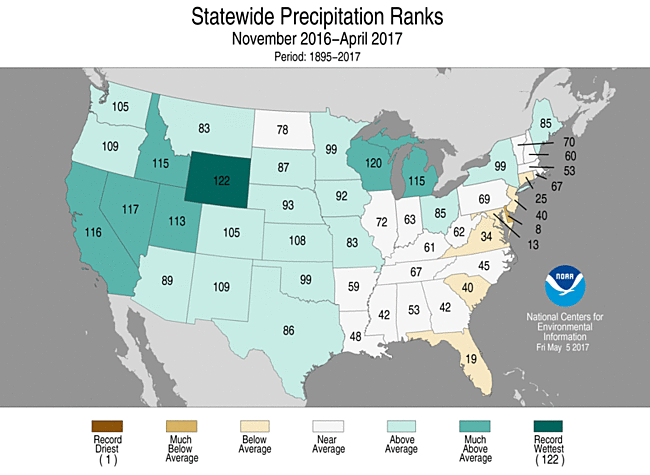

Drought has plagued many parts of the U.S. West for the better part of two decades, so the winter of 2016-17 came as a welcome relief. Every contiguous state from the Continental Divide westward has racked up well-above-average precipitation over the last few months (Figure 1). Wyoming saw its wettest November-to-April period in 122 years of recordkeeping, and four other western states made their top-ten-wettest lists for that six-month period.

|

| Figure 2. Statewide precipitation ranks for the period November 2016 through April 2017, calculated for the 122-year period of record. High numbers correspond to wetter years, with 122 record wet and 1 record dry. Image credit: NOAA/National Centers for Environmental Information. |

Wet winters don’t guarantee a relatively quiet fire season the next summer, but they help in a big way. Deeper mountain snowpack tends to persist longer into the spring, which means a shorter interval for soils to dry out in the summer heat. Moreover, trees drawing on deep soil moisture don’t dry out as quickly, which reduces the risk of tinder-dry forests. On the flip side, wet years tend to produce an abundance of grasses. "In dry years the fuels are more combustible, while in wet years there are more fuels," said Jan Null (Golden Gate Weather Services) in an email. "But historically statewide, the acreage burned in California is less in years following wet years than dry years," said Null.

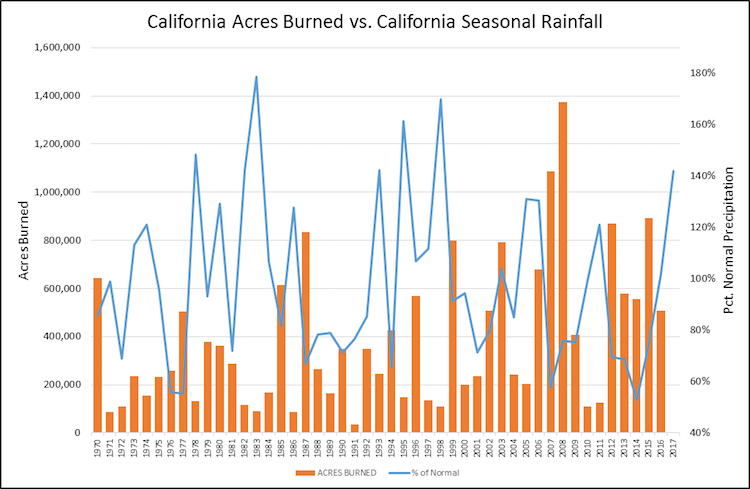

The San Jose Mercury-News pored through 40 years of California records on winter precipitation and the acres burned in the following summer. They showed that 7 of the state's 10 worst fire seasons from 1970 to 2009, but only 2 of the 10 "best" fire seasons, took place after drier-than-average winters. Similar patterns emerge in a data set for 1970 - 2016, provided by Null: 8 of the 10 seasons with the greatest fire extent, but only 3 of the 10 with the least extent, occurred after drier-than-average wet seasons. These numbers show that winter moisture is only part of the picture, as a lot also depends on how summer itself unfolds. For example, fires may ignite more often in a summer with plenty of thunderstorms that produce little rain but frequent cloud-to-ground lightning strikes and strong downburst winds.

|

| Figure 3. Number of acres burned in wildfire across California, by year (orange bars) vs. statewide percentage of average precipitation in the preceding water year, defined as July through June. The value for 2016-17 is the percentage of total July-June precipitation already received through April 30. Image credit: Jan Null, @ggweather. |

More than winter moisture in play

"California’s fire season always needs to be kept in the context of its mostly Mediterranean climate, which is defined by a 'summer drought,'" Null pointed out. "This means that fire danger is exacerbated later into the summer and fall with continued drying from May through September."

Long-range outlooks from The Weather Company and NOAA lean toward a hotter-than-average summer across parts of the West, especially toward late summer. Intense summer heat can parch a landscape quickly, and the fierce downslope winds that can slam coastal California in late summer and early autumn (after months of dryness) can boost fire risk regardless of the prior winter. The catastrophic Oakland firestorm of October 1991, which killed 25 people and destroyed more than 3000 homes, occurred after what was by far the least active summer fire season for California in data going back to 1970.

“The bottom line is that every year there is the potential for California to have catastrophic fires,” Null said.

|

| Figure 4. The Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook for July-August 2017 shows elevated potential over parts of California and Nevada, as well as south Georgia and Florida. Image credit: National Interagency Fire Center. |

Grassland fire: a big concern this year

The same moisture that’s helping to rejuvenate western forests and water supply is also spawning a bumper crop of grasses, weeds, and other “fine fuels,” as they’re called. These twigs and grass blades respond quickly to heat and dryness, so as summer progresses they may pose an increasing risk for low-rise fires. Another potential fuel source, even after a wet winter, are the widespread stands of trees that were killed by California’s 2011-2016 drought.

The summer outlook from NIFC calls for a slower-than-usual progression of fire risk across the West: the wildfire threat is expected to increase and work its way northward in typical seasonal fashion at lower elevations, but it may be delayed at higher elevations because of the ample snowpack. By July and August, the lower foothills of northern California and the rangelands of northern Nevada may be at higher-than-usual wildfire risk (Figure 4) because of the abundance of fine fuels on hand this year.

Drought-stricken areas of the Southeast should benefit from widespread heavy rain over the next week, which may extend across most of the Florida peninsula. The region could use a break: severe to extreme drought covered most of the area from Atlanta to Orlando in last week’s U.S. Drought Monitor. Orlando received just 3.35” of rain for the period from January 1 to May 21, a record-low amount for the year to date and far below the average of 13.02”. With any luck, Orlando will double that year-to-date amount in the next week.

As of Sunday, Florida had experienced 2,273 wildfires, burning a total of 171,397 acres. That’s close to 50% above the annual average over the last five years.