| Above: A riding lawnmower rests on its end in a field in downtown Pacific, Mo., on Thursday, May 4, 2017. Pacific officials estimate 170 homes and businesses flooded. Image credit: Robert Cohen/St. Louis Post-Dispatch via AP. |

Damages from flooding, tornadoes, large hail, and other extreme weather associated with the past week’s intense midlatitude cyclone in the central U.S. are likely to top $1 billion, according to a summary from insurance broker Aon Benfield. “With several rivers and streams additionally forecast to crest in the coming days, it will likely take weeks until the full scope of the event is realized,” they said.

|

| Figure 1. Waters flood the intersection of Interstate 44 and Highway 141, Tuesday, May 2, 2017, in this view from the top floor of the Drury Inn in Valley Park, Mo. The flooded Meramec River has shut down all traffic at the intersection. Image credit: J.B. Forbes/St. Louis Post-Dispatch via AP. |

|

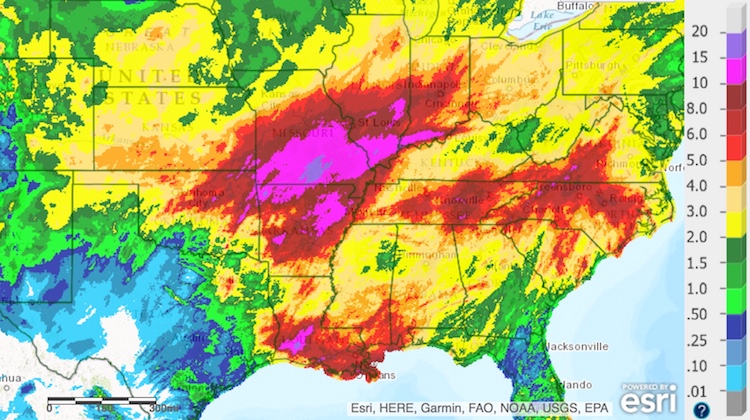

| Figure 2. Total precipitation estimated from radar, satellite and ground reports for the 14-day period from 12Z (8:00 am) Friday, April 21, 2017, to Friday, May 5. Image credit: NOAA/NWS Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service |

Aon Benfield noted that at least 14 locations on 10 rivers have set all-time record-high crests during the past week:

• Current River at Doniphan, Missouri (previous record: March 1, 1904)

• Current River at Van Buren, Missouri (previous record: March 26, 1904)

• Meramec River near Sullivan, Missouri (previous record: August 1, 1915)

• North Fork White River near Tecumseh, Missouri (previous record: August 1, 1915)

• St. Francis River at Patterson, Missouri (previous record: December 3, 1982)

• Jacks Fork at Eminence, Missouri (previous record: November 15, 1993)

• Meramec River near Steelville, Missouri (previous record: July 27, 1998)

• Big Piney River at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri (previous record: March 19, 2008)

• Gasconade River near Hazelgreen, Missouri (previous record: March 19, 2008)

• Black River at Pocahontas, Arkansas (previous record: April 28, 2011)

• Illinois River near Watts, Oklahoma (previous record: December 28, 2015)

• Gasconade River at Jerome, Missouri (previous record: December 30, 2015)

• Gasconade River near Rich Fountain, Missouri (previous record: December 30, 2015)

• Meramec River near Eureka, Missouri (previous record: December 30, 2015)

Hundreds of water-swamped roads have been closed across Missouri and Arkansas, including two large interstate segments in southeast Missouri.

Flooding shifts to northeast U.S., southeast Canada

The large upper-level storm that generated the central U.S. cyclone has been parked across the Midwest and southeast Canada for several days. As spokes of energy rotate around the low, new bursts of rain have been developing across the region.

Very heavy rain in association with a warm front socked the New York City region on Friday afternoon. Parts of Manhattan’s West Side Highway were under water, and the main entrance to Penn Station was flooded. The National Weather Service reported that numerous water rescues were taking place. Newark International Airport received an unofficial total of 3.05” in the eight hours ending at 3:00 pm EDT, with 2.99” at New York’s Central Park. In Newark records extending back to 1931, only six other days in springtime (March – May) have been wetter.

A wet April across southeast Canada has laid the groundwork for significant flooding. Lake Ontario is currently at its highest level in more than 20 years, and the lake could rise even further in coming days. Canada’s largest city, Toronto, which sits on Lake Ontario’s northwest shore, could receive upwards of 90 mm (3.54”) of rain through Saturday. The heaviest was expected on Friday, according to Environment Canada. A new flood control system on Toronto’s lakefront is being put to its first major test. “We’ve been planning for this kind of event for many, many years,” waterfront specialist Nancy Gaffney (Toronto Region Conservation Authority) told CTV News Channel.

|

| Figure 3. Residents use a canoe as they bring supplies through flooded streets of the Ile-Mercier district of Ile-Bizard, Quebec, on Friday, May 5, 2017. Forecasts are calling for several more days of rain. Image credit: Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press via AP. |

Climate change, heavier rains, and flood risk

It’s well established that in many parts of the world, including much of North America, the heaviest periods of extreme rain and snow are getting even heavier. As human-produced greenhouse gases warm the atmosphere, they encourage more moisture to enter the atmosphere from the ocean, allowing more water vapor to be concentrated into localized showers and thunderstorms as well as tropical cyclones and large midlatitude systems.

The rains in Missouri were certainly intense from a historical perspective. In Springfield, the calendar-day total of 4.31” on Sunday, April 30, was the highest for any springtime day (March through May) in Springfield records going back to 1888.

Attribution studies can help estimate how much the odds of a rain like this at a given location have been boosted by human-produced climate change. It’ll take time for such work to be done for this week’s billion-dollar cyclone. However, a study coordinated by Climate Central last year found that climate change has made the rainfall pattern that drove Louisiana’s “no-name” flood disaster in August—the most expensive U.S. natural disaster of 2016—at least 40% more likely than it was a century ago.

The evolving riverscape

There’s another human element at work in the central U.S. floods. Major reshaping of flood channels, to accommodate agriculture and development, has torqued the way in which small creeks and streams feed into the region’s great rivers, the Missouri and Mississippi. These rivers are now significantly narrower, so rainfall doesn’t have to be as widespread or intense as before in order to generate very high water levels.

As of Friday afternoon, more than 91 miles of the Mississippi River had been closed to all boat and ship traffic, including a 14-mile stretch near St. Louis and a longer segment from Chester to Cairo. Along this latter segment, the river was predicted Friday to crest near 48 feet on Sunday. The only higher crests in more than a century of data at Cape Girardeau were the 48.86’ on January 2, 2016, and 48.49’ on August 8, 1993. The latter was part of the massive Great Flood of 1993, which lasted for weeks on end and wreaked $15 billion in damage. However, the rainfall that triggered the 2016 flood was far less extensive and prolonged.

|

| Figure 4. A sign floats in the downtown floodwaters of Grafton, Ill., on July 20, 1993, as boats used to transport residents to their water-surrounded homes sit in dock. Image credit: Eugene Garcia/AFP/Getty Images. |

The similar response to very different rainfall events can be explained by changes in landscape, according to Dr. Robert Criss (Washington University). The 2016 flood “was essentially a winter flash flood on a continental-scale river,” Criss said in a WU news release. “The Mississippi has been so channelized and leveed close to St. Louis that it now responds like a much smaller river.”

I caught up with Criss and asked him for his take on the ongoing situation:

“This 2017 flood has several similarities to that of 16 months ago. Like then, many small basins have just set record water levels, because the forcing of heavy rain delivered over a period of 3-4 days is the type of event to which basins of this scale strongly respond. Small creeks (watersheds of less than 100 square miles) did not respond so dramatically; instead, they respond most strongly to heavy rainfall delivered in less than 6 hours.

“Huge rivers (Mississippi, Missouri) should NOT be responding so dramatically to this storm. What we are seeing is an unnatural response because we have, in effect, made these huge rivers respond like small basins due to construction—levees too high, too long, too close to the river, and training structures (wing dikes, etc.) in the river channel.”

Criss added: “For nearly 1000 miles, the middle Mississippi and lower Missouri Rivers are only one-half as wide as they were historically. Climate change / intensified storms will make small basins respond more dramatically than they have in the past. However, this is not the primary explanation as to why huge Midwestern rivers are approaching, or even setting, record levels. Channelization/constriction makes small rivers out of big ones, and greatly increases their probability of severe flooding, in a way my papers account for.”

In one of those papers, published in February in the journal Hydrologic Processes, Criss and colleague Mingming Luo (China University of Geosciences), used new techniques to support Criss’s longstanding hypothesis that indices of flood risk, such as the 100-year recurrence interval, seriously underestimate the present-day risk of flooding in many parts of the central U.S., especially the most highly channelized areas. “Terms such as ‘100‐year flood’ are now so overused that they have become a national joke,” they write. “Risk underestimation is serious because it fosters commercial development of floodplain areas.”