| Above: A pedestrian in Phoenix walks through a flooded street with a hand truck to get sand bags to deliver to local businesses during a flash flood as a result of heavy rains on Tuesday, Oct. 2, 2018. Image credit: AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin. |

The remnants of former Hurricane Rosa made their presence felt across far northwest Mexico and the Southwest U.S. on Tuesday. Phoenix picked up 2.36”, which makes Tuesday the wettest October day in the city’s 123 years of weather records (beating 2.32” from October 14, 1998). Tuesday also ranks as the eighth-wettest calendar day on record in Phoenix. Totals of 2” – 3” across the Phoenix metro area led to widespread flash flooding, and there was a CoCoRaHS report of 3.45” just south of Flagstaff. The largest rain total from Rosa’s remnants through 3 am EDT Wednesday was 6.89” at Towers Mountain, Arizona—still well short of the state record for storm totals associated with a tropical cyclone (12.01” from Nora in 1997). See the weather.com article for more on Rosa’s impacts.

|

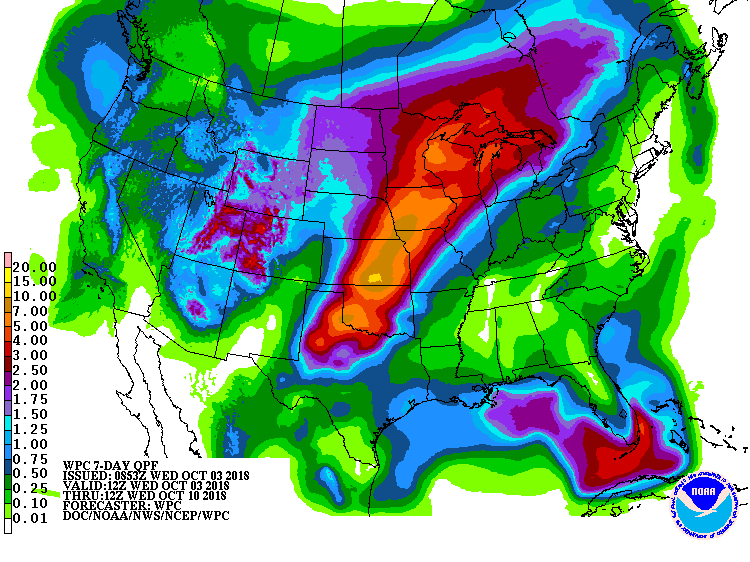

| Figure 1. Forecast for precipitation over the 7-day period starting at 8 am EDT Wednesday, October 3, 2018. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/WPC. |

Flood threat migrates to Plains, Upper Midwest this weekend

Flash flood watches are still in effect across parts of the Southwest, including Utah, but the nation’s biggest rain/flood threat will shift to the Great Plains and Upper Midwest this weekend. Several days of intense rain are expected to develop along an oscillating frontal zone between a cold autumn storm in the West and persistent warm weather in the East.

Seven-day totals of 5” – 10”, with some localized totals in the 10” – 15” range, are projected by the NOAA/NWS Weather Prediction Center to fall along a belt from Texas to Wisconsin (see Figure 1 above). These rains are likely to ensure that 2018 will be the wettest year in Madison, WI, since at least 1884. With soil moisture running high across much of the Plains and Upper Midwest, flooding may become a serious concern.

|

| Figure 2. Soil moisture is running well above average for this time of year across much of the belt from Texas to Wisconsin where heavy rains are expected over the next week. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPC. |

Leslie: A hurricane at last

In one of the less-dramatic intensifications we’ve seen lately, the ever-gradually-organizing Tropical Storm Leslie was upgraded by the National Hurricane Center at 5 am EDT Wednesday, becoming the sixth hurricane of the Atlantic season thus far.

We’re now up to 12 named storms and 6 hurricanes, which is pushing toward the top end of the seasonal outlooks put forth by various groups. The yearly average for an entire Atlantic season during 1981–2010 (which includes both the pre-1995 quiet era and the post-1995 active period) is 12.1 named storms, 6.4 hurricanes, and 2.7 major hurricanes. Only one Atlantic hurricane thus far—Florence—has qualified as a major (Cat 3 or stronger). The amount of accumulated cyclone energy thus far in the Atlantic, 89.7 units, is just slightly above the 1981–2010 average of 85.3 for this point in the season, according to Colorado State University.

|

| Figure 3. Infrared image of Hurricane Leslie at 1435Z (10:35 am EDT) Wednesday, October 3, 2018. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

Wednesday could end up being Leslie’s peak day. Thunderstorm activity (convection) around Leslie’s center was not especially strong, but it was fairly symmetric and wrapping around a large, distinct eye. Top sustained winds were up to 80 mph as of 11 am EDT. Leslie’s winds could increase a bit more: the hurricane was stalled well east of Bermuda above sea-surface temperatures of up to 26-27°C (79–81°F), and wind shear was a moderate 10 – 15 knots.

From Thursday to Saturday, Leslie will get tugged northward, bringing it over cooler waters and likely denting its strength. A brief eastward drift is then likely early next week before an intensifying upper-level low in the North Atlantic shoots Leslie on an accelerating track toward the Azores. Leslie will most likely be a post-tropical storm by that point.

Leslie is generating long-period swells of 6 – 8 feet that will affect portions of the southeastern coast of the United States, Bermuda, and the Bahamas through Thursday. Persistent onshore winds will accompany these swells, generating dangerous surf and rip currents. Large swells from the hurricane are expected to increase near the coasts of New England and Atlantic Canada by the end of the week.

Watching the Caribbean for development

A broad area of low pressure called a Central American Gyre (see tweet below) was located over the southwestern Caribbean Sea on Wednesday afternoon, and was generating disorganized heavy thunderstorms over much of the southwest and central Caribbean. This system has the potential to develop into a tropical depression early next week as it drifts slowly northward, and it will bring dangerous heavy rains to portions of Central America this week.

Per the latest #GFS forecast, a Central American Gyre (#CAG) is developing over the Western #Caribbean. This system satisfies the criteria of a CAG because it has closed cyclonic flow & a radius of maximum winds >500km from the circulation maximum.

— Philippe Papin (@pppapin) October 2, 2018

URL: https://t.co/0Jxrc1nPQF pic.twitter.com/F77gtNtFRB

Satellite loops on Wednesday showed that the low, which had not yet been given an “Invest” designation, had a surface circulation that was attempting to get organized a few hundred miles south-southwest of Jamaica. The heaviest thunderstorms lay well to the east, near Hispaniola. Wind shear was a prohibitively high 30 – 40 knots, due to the presence of a strong subtropical jet stream.

The shear will relent this weekend, when the subtropical jet stream is predicted to lift to the north so that it is positioned over Cuba. This will create a region of lower wind shear over the central and western Caribbean, and recent runs of the GFS and European model have been suggesting that a tropical depression could develop early next week. This was also predicted by over 30% of the 70 ensemble members of the 0Z Wednesday GFS and European models. Any tropical cyclone that develops is likely to become entangled with an upper-level low pressure system, making the system a large and slow-to-intensify sloppy mess of a storm that will primarily be a heavy rain threat. The track such a storm might take is anyone’s guess at this point, and we’ll just have to watch how the models depict the evolution of this potential threat in coming days. In their 8 am EDT Wednesday Tropical Weather Outlook, NHC gave the system 2-day and 5-day odds of development of 0% and 30%, respectively.

|

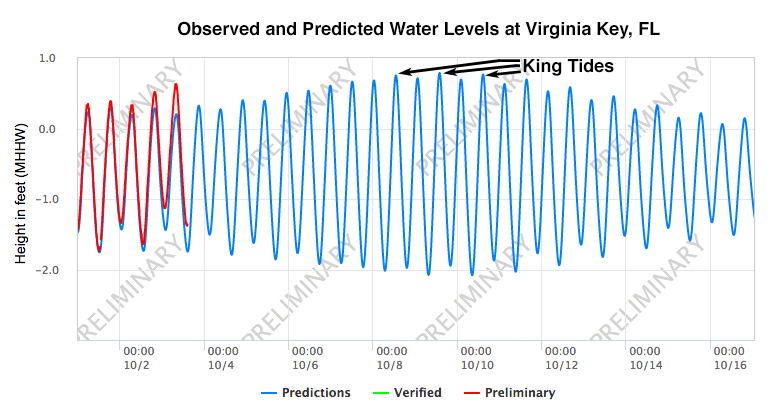

| Figure 4. The predicted daily tidal cycle (blue line) at Virginia Key, FL for the first two weeks of October 2018. The observed water levels (red line) for October 1 – 3 showed water levels up to 0.4’ above normal were occurring. This was due to persistent onshore winds combined with the wave run-up from Hurricane Leslie’s swells. There are two high tides and two low tides per day. The highest high tides and lowest low tides occur during the time of the new moon (October 8). The tidal range between low tide and high tide is about 2 – 3 feet. The highest tides of the year will occur on Monday – Wednesday next week (Oct 8 – 10), and will be about 0.7 feet above high tide (Mean Higher High Water, or MHHW). Image credit: NOAA Tides and Currents. |

The king tides are next week

Each month, the Earth experiences two periods that have higher tides than normal, due to the phase of the moon. The highest tides occur during the new moon or full moon, since the pull of the moon aligns with the pull of the sun at those times to make the oceans bulge out farther. The new moon in October occurs on Monday, October 8, and the highest tides of the month will occur within two days of that date. Next week’s tides will also be among the very highest tides of the year--the king tides. These happen when Earth gets near its January perihelion (the closest the Earth gets to the sun during the year), when the combined pull of the sun and the moon bring tides to their maximum level. Along the Southeast U.S. coast, the seasonal cycle of ocean currents and SSTs also controls when the king tides are at their highest, often resulting in an October maximum rather than a January maximum (during perihelion).

Along the Southeast U.S. coast, water levels were already running high this week, due to persistent onshore winds combined with the wave run-up due to Hurricane Leslie’s swells pounding ashore. At Virginia Key, FL (next to Miami Beach), tides were about 0.4’ above normal on Wednesday morning (Figure 4). If we do get a Tropical Storm Michael next week, it will have the potential to cause much higher storm surge damage than normal, due to it hitting during the king tides.

Dr. Jeff Masters wrote the Caribbean and king-tide sections of this post.