| Above: Floodwaters coursed down the Wailuku River near Hilo, Hawaii, on Thursday, August 23, 2018, as rains of 10” to 20” struck the region. Image credit: Jessica Henricks via AP. |

Hurricane Lane has embarked on its long-awaited weakening trend, but that may not be enough to spare Hawaii from a prolonged round of torrential rains, floods, mudslides, and related havoc.

Update: As of 11 am EDT Friday (5 am HST), Lane’s top sustained winds were down to 110 mph, making it a top-end Category 2 storm. Lane’s center was located about 145 miles west-southwest of Kailua-Kona and about 180 miles south of Honolulu. Lane was moving north at just 5 miles per hour. A Hurricane Warning was in effect for Oahu, Maui, Lanai, Molokai, and Kahoolawe, with a Tropical Storm Warning for the Big Island and a Hurricane Watch for Kauai and Niihau.

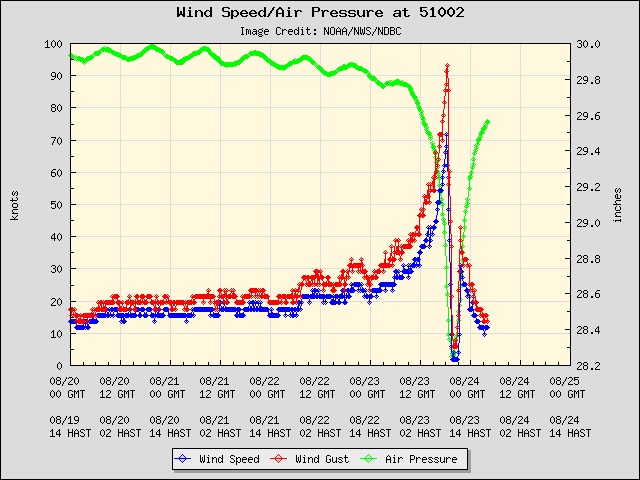

The U.S. Air Force and NOAA reconnaissance aircraft have left the Central Pacific, but buoy 51002 southwest of the Big Island gave us a glimpse of the inner workings of Lane as the hurricane passed directly over it on Thursday (see Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Easterly winds of 83 mph, gusting to 105 mph, were recorded at a height of about 13 feet above sea level as the northern eyewall of Hurricane Lane passed over buoy 51002 at 2:20 pm EDT (8:20 am HST) Thursday, August 23, 2018. The winds dropped to around 2 mph for about an hour as the eye passed over the buoy, while the central pressure bottomed out at 28.25” (about 957 mb). Waves of 32 feet slammed the buoy just after the peak winds. Lane’s highest winds were likely occurring in its eastern eyewall. Image credit: NOAA/National Buoy Data Center. |

Why Lane is weakening, and why it may not matter for Hawaii

Steadily increasing wind shear is the main factor in Lane’s decay. Although the hurricane has maintained a strong core of showers and thunderstorms (convection), its inner structure was becoming increasingly compromised on Thursday night, and that process will accelerate on Friday. Already, Lane’s eye had become obscured on satellite by late Thursday (though it was still visible on radar), and the hurricane’s upper-level outflow was becoming more and more asymmetric.

|

| Figure 2. Infrared image of Hurricane Lane southwest of Hawaii’s Big Island at 12:45 am EDT Friday, August 24, 2018 (6:45 pm HST Thursday). Image credit: NASA/MSFC Earth Science Branch. |

As the shear ramps up further—especially on Saturday, when it may reach 30 – 40 knots, as predicted by the 0Z Friday run of the SHIPS model—the storm will become more tilted, with the strongest winds increasingly limited to the east side of its center. The shear will also inject an increasing amount of dry air from the southwest into the storm. Lane will likely become a Category 1 hurricane by late Friday, if not sooner, and a tropical storm by Saturday.

This weakening trend is no surprise—it’s been predicted for days—and it will do little to quash Lane’s potential to be a hugely costly and disruptive storm for Hawaii. Even as Lane’s core degrades quickly, the hurricane’s large circulation will take a long time to spin down, and the storm’s winds will continue to push vast amounts of tropical moisture across the islands from east to west into the weekend. As the winds and moisture encounter higher terrain, mammoth amounts of rain will be squeezed out. Lane’s slow movement, especially from Friday through Saturday, will only exacerbate the situation.

Hawaii photographer Ken Boyer told me that he saw "at least 30" homes flooded in Hilo. He filmed this house's yard, which was completely submerged by water.

— carla herreria (@carlalove) August 24, 2018

Heavy rains are expected across the state over the weekend. The risk for flash flooding is very real.#HurricaneLane pic.twitter.com/5JpFgQ13pw

Colossal rainfall amounts may produce locally devastating impacts

CPHC is predicting widespread 10” – 20” storm totals from Lane across Hawaii, with local totals exceeding 30”. It would not surprise me to see at least one or two amounts topping 40” by Sunday. As these rains flow across rugged terrain and through narrow valleys, we can expect numerous mudslides, rock falls, and road closures. The risk of major flooding will increase on Friday and into Saturday, especially across the Big Island and Maui. The west coast of the Big Island—which had received only minor amounts of rain through late Thursday—will likely have its greatest chance of downpours from Friday into early Saturday, as Lane continues northward and winds there gain more of an onshore component. Periods of heavy rain will extend westward through Oahu to Kauai through the next several days.

Parts of the northern and eastern Big Island had already received 15” – 20” of rain from Lane’s outer rainbands. The 24-hour precipitation summary for Hawaii issued at 12:45 am EDT Friday (6:45 pm HST Thursday) included:

Hakalau: 18.68”

Waiakea Experimental Station: 18.09”

Saddle Quarry: 16.09”

Hilo Airport: 13.05”

Amounts were generally less than 5” on Hawaii’s other islands as of Thursday evening.

As of 4:30 pm HST Thursday, Hilo had received 25.77” for the month of August. The city is virtually certain to break its all-time August record of 26.92”, set in 1991, before Lane is over.

Brian McNoldy (University of Miami/Rosenstiel School) is uploading extended radar animations for Hawaii as Lane approaches.

|

| Figure 3. Forecast track and “cone of uncertainty” for Lane as of 11 pm EDT (5 pm HST) Thursday, August 23, 2018. The cones are constructed based on typical forecast errors over the past few years such that a hurricane can be expected to fall within the cone about two-thirds of the time. The cone suggests that Lane’s center will most likely remain well south and west of each Hawaiian island. However, Lane’s effects will extend far from its center, touching virtually all of the islands in some form or fashion. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPHC. |

Could Lane angle toward Maui?

A major disagreement among models persisted into Thursday night, complicating the track forecast for an already tough-to-predict hurricane. The Thursday-night runs of the HWRF and GFS models (0Z Friday) continued to show that Lane’s northward track will arc toward the north-northeast on Friday, bringing the storm very close to Maui and its neighboring islands by late Friday. The European model (ECMWF), which had been insisting on a north-northwest track that would keep Lane more than 200 miles from Maui, shifted dramatically in its 12Z Thursday run toward the HWRF/GFS solution. However, the 0Z Friday run of the ECMWF weakened Lane quickly, shoving it west-northwest away from the islands much more quickly than previous runs or other models.

Given the consistency of the operational HWRF/GFS runs, we must keep in mind the possibility that Lane will move fairly close to Maui before it weakens enough to take the sharp west hook indicated by all models by Saturday. Such a path could fall outside the right-hand side of the forecast “cone of uncertainty” issued at 11 pm EDT Thursday (see Figure 3 above). These cones are not hard-and-fast barriers; they reflect the historical probability that a hurricane will stick close to the official prediction. On average, a given storm will stray outside the cone about one out of three times. In its 11 pm EDT forecast discussion, CPC acknowledged the higher-than-usual uncertainty still present with Lane: “Although the official forecast does not explicitly indicate Lane's center making landfall over any of the islands, this remains a very real possibility.”

If Lane moved close to Maui, it could bring a period of intensified rains and stronger winds, but the larger threat of prolonged heavy rains will be in place regardless of whether Lane takes this brief detour or not. On the other hand, if Lane were to weaken especially quickly, in line with the latest ECMWF run, then the flood threat would decrease across the islands.

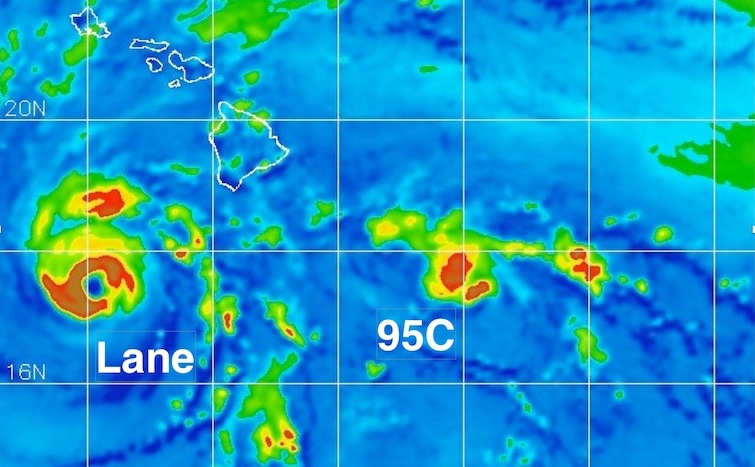

Another wrinkle: Invest 95C

As if the Lane situation weren’t complex enough, a new disturbance about 300 miles to the east developed enough convection and spin on Thursday to be classified as Invest 95C. The disturbance formed along a stream of moisture associated with the Intertropical Convergence Zone. This moisture channel will be directed squarely at the Big Island and Maui on Friday and Saturday, and 95C will likely move west-northwest along it toward the islands.

|

| Figure 4. Convection (showers and thunderstorms) associated with Hurricane Lane (left) and 95C (center), as shown in microwave radiometer imagery from the AMSR2 instrument on Thursday afternoon, August 23, 2018. Image credit: Philippe Papin, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. |

If 95C strengthens enough, the spin associated with it could interact with Lane and the higher terrain of the islands in such a way as to raise the odds of Lane’s moving toward Maui and merging with 95C. Such an interplay would be so unusual and complicated that we can’t expect forecast models to nail it with precision. More likely, 95C's main role will be to deliver an additional slug of moisture to an area that doesn’t need it.

Other impacts from Lane

The odds of sustained hurricane-force winds is very low across most of the islands, with the possible brief exception of Maui and nearby islands around Friday night if the scenario above were to play out. However, the chance of widespread tropical-storm-force winds (sustained winds of 39 mph or stronger) is considerably higher. These winds can be strong enough to topple trees and power lines, especially with saturated soils.

|

| Figure 5. Left: the probability of experiencing tropical-storm-force winds (sustained at 39 mph or more) at some point between Thursday morning, August 23, 2018, and Tuesday morning, August 28, based on the forecast track as of Thursday evening. Right: the probability of hurricane-force winds (sustained at 74 mph or more). If Lane takes a turn toward Maui, as discussed above, hurricane-force winds could draw closer to Maui and nearby islands. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPHC. |

Tornadoes are somewhat more likely with Lane than with Hawaii’s other recent brushes with tropical cyclones, in part because of the storm’s strength and path. As it approaches, Lane will put each island in its right front quadrant, the most favored location for the wind shear that can lead to tornadoes. On average, Hawaii sees less than one tornado a year, with 42 recorded from 1955 to 2015, according to the Tornado History Project. Most of these occurred in association with winter storms rather than tropical cyclones. Four of Hawaii’s tornadoes have been rated F2, the most recent being on May 18, 1982.

Storm surge is generally less of a threat in Hawaii compared to Atlantic hurricanes hitting the U.S. coast, since the Hawaiian Islands are surrounded by deep water that prevents a storm surge from building to large heights. The worst-case surge from a mid-strength Category 2 hurricane hitting Oahu, for example, is only four feet in Pearl Harbor, which is the most vulnerable portion of Oahu to storm surge (see wunderground’s Maximum of the "Maximum Envelope of Waters" (MOM) storm tide image).

Marine forecasts on Thursday night predicted that waves of 12 - 16 feet will affect most of the islands, especially leeward-facing shores.

What about Kilauea? Experts say there's little risk that the effects of the hurricane will make things worse at the Kilauea volcano on the Big Island, where hundreds of homes have been lost from this summer's lava flows. "Effects of hurricane-related torrential rainfall on the lower East Rift Zone lava flow will be minimal," Janet Babb, a geologist at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, told weather.com. "Where the interior of the flow is still hot, heavy rain will likely result in the formation of steam."

For more details on potential impacts from Lane, see the frequently updated weather.com feature story.

Dr. Jeff Masters contributed to this post.