| Above: Firefighters battle the Rocky Fire (also known as the Peak Fire) along the Ronald Reagan (118) Freeway in Simi Valley, Calif., Monday, Nov. 12, 2018. As of late Monday, the fire was 100% contained after burning 186 acres. Image credit: AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu. |

Even as Southern California faces at least one more day of fierce wind and bone-dry conditions, state officials and residents are trying to come to terms with the level of death and destruction left by the past week’s wildfires. As of Monday night, at least 42 people were reported killed by the Camp Fire, which decimated the city of Paradise on Thursday. The fire is now the deadliest in California history, beating the grim record of 29 set in a October 1933 blaze at Los Angeles’s Griffith Park. More than 200 people in the Camp Fire area remained missing on Monday, and it is very possible more victims will be found in and near Paradise as the search expands into areas that were too dangerous or difficult to assess right away.

The Camp Fire is also the most destructive blaze in modern California history, with at least 7177 structures consumed, a number that may rise even further. On Monday evening, Cal Fire released an online tool to help residents find whether their homes have been damaged or destroyed in the fire.

Only three injuries had been reported from the Camp Fire as of Monday—which speaks to the lethal nature of the fast-moving fire itself: virtually everyone escaped without injury or died trying. There was only one route out of Paradise, which led to immense congestion as panicked residents left the area in the near-darkness produced by thick smoke. The New York Times paints a vivid picture of the nightmarish scenario that prevailed during the evacuation of Paradise.

In Southern California, two deaths were reported with the Woolsey Fire, which swept across large parts of eastern Ventura and western Los Angeles counties on Friday. As of Monday morning, the Woolsey Fire had burned more than 91,000 acres and the Camp Fire had burned 117,000 acres. It’s extremely unusual if not unprecedented to have simultaneous fires of this scope in both Northern and Southern California. At least 370 structures have been lost to the Woolsey Fire—including several celebrity mansions—and that number is expected to grow.

Santa Ana winds coupled with extremely low humidity will continue to stoke the fire threat across Southern California into midweek, although the winds should be gradually winding down. Tuesday’s strongest winds may be in the hills south of Los Angeles, where the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center is calling for “extremely critical” fire weather—its most dire rating—on Tuesday. “Critical” fire weather is predicted to extend northwestward into the Woolsey Fire area on Tuesday, especially early in the day, with gusts in the 40 - 60 mph range across win-prone areas.

|

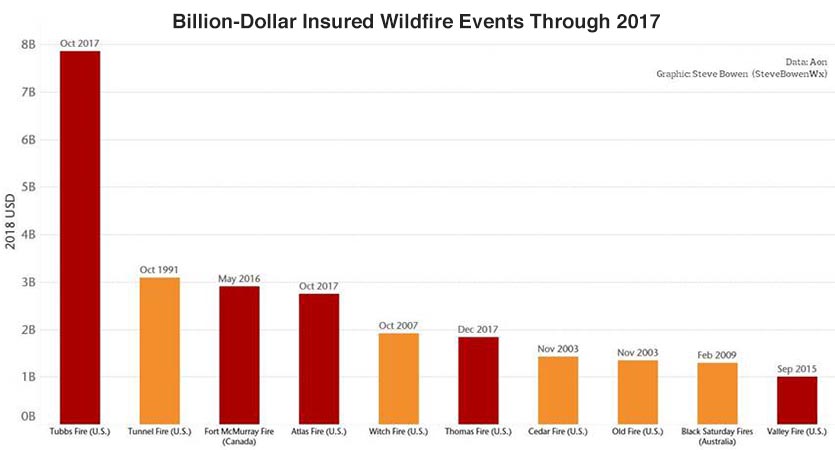

| Figure 1. Global wildfires between 1990 – 2017 that caused at least $1 billion (2018 dollars) in insured damages, according to insurance broker Aon. Events that occurred since 2015 are shown in red, and older ones are in orange. The two billion-dollar fires from 2018 in California are not shown. Image credit: Steve Bowen, Aon. |

An unprecedented onslaught of California billion-dollar wildfire disasters

The Camp Fire is highly likely to eclipse $2 billion in damages, making it the state’s second billion-dollar wildfire disaster of 2018, along with the $1.8 billion Carr Fire in August. It is uncertain yet if Malibu’s Woolsey Fire will eclipse $1 billion in damages, according to Steve Bowen of insurance broker Aon.

There were just five billion-dollar wildfires (in 2018 dollars) in modern world history that occurred before 2015. With the addition of the November 2018 Camp Fire in California, the planet has seen seven additional billion-dollar wildfire disasters from 2015 to 2018—six of them in California. (Note that a number of urban fires up through the 19th century—such as London’s Great Fire of 1666 and the Great Chicago Fire of 1871—were hugely catastrophic in terms of their impact on the societies and economies of their time, though.) In total, California has suffered ten of the planet's twelve billion-dollar wildfires.

In an email, Bowen commented: “The combination of increasing exposure into known fire-prone areas (known as the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI)), insufficient fire suppression tactics, growing climate change enhancements to weather phenomena, changing fire behavior, and a nearly year-round fire season are all leading to greater wildfire risk in California. It’s a concerning trend that will somehow need to be addressed. Unfortunately, there are no simple solutions.”

Commentary: A hot take on fire risk, and a thoughtful follow-up

President Donald Trump got major blowback after a tweet sent on Saturday: “There is no reason for these massive, deadly and costly forest fires in California except that forest management is so poor. Billions of dollars are given each year, with so many lives lost, all because of gross mismanagement of the forests. Remedy now, or no more Fed payments!” Brian Rice, president of the California Professional Firefighters union, which represents more than 30,000 first responders, declared in a statement: "The president’s message attacking California and threatening to withhold aid to the victims of the cataclysmic fires is ill-informed, ill-timed and demeaning to those who are suffering as well as the men and women on the front lines.”

As pointed out by Steve Bowen above, there are many factors at work, not just one, in California’s recent spate of fire disasters. Daniel Swain, author of the California Weather Blog, fired off a superb tweetstorm on Saturday drawing the links between California’s recent fire history and our evolving climate, especially the trend toward hotter and drier autumn weather. Another thoughtful voice in the mix is Stephen Pyne (Arizona State University), one of the nation’s premier wildfire experts and the author of more than 30 books. In an essay for Slate, Pyne puts the California fire surge and how we might address it into powerful and eloquent context.

Many of the most destructive Western fires in recent years have ripped across the wildland-urban interface, where increasing numbers of Americans have been moving. Pyne offers a striking historical comparison:

“Aerial photos of savaged suburbs tend to show incinerated structures and still-standing trees. The vegetation is adapted to fire; the houses aren’t. Once multiple structures begin to burn, the local fire services are overwhelmed and the fire spreads from building to building. This is the kind of urban conflagration Americans thought they had banished in the early 20th century. It’s like watching measles or polio return. Clearly, the critical reforms must target our houses and towns and revaccinate them against today’s fire threats. The National Fire Protection Association’s Firewise program shows how to harden houses and create defensible space without nuking the scene into asphalt or dirt.”

Pyne adds: “Too often, whether we’re talking about politics or fire management, the discussion ends up in absolutes. We leave the land to nature, we strip it, or we convert it to built landscapes. We have either the wild or the wrecked. In fact, there are lots of options available, and they will work best as cocktails.”

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.