| Above: Departures from average temperature (1979-2000 base period), in degrees Celsius, on Monday, January 27, 2020, as analyzed by the GFS/CFSR model. Image credit: Climate Change Institute, University of Maine. |

It’s normal for the midlatitudes to be milder than the poles, but this month has taken that seasonal expectation to extremes. We’ve seen a strikingly mild January across most of the northern midlatitudes, from the United States to Eurasia, while Alaska has shivered through persistent cold and the Arctic has seen a modest rebound in sea ice extent.

At the heart of this pattern is a strong and compact polar vortex in the stratosphere, miles above the Arctic. Thus far this winter, the vortex hasn’t seen any major disruptions of the type that perturb the broad-scale, lower-level (tropospheric) polar circulation and allow large volumes of cold air to spill into the midlatitudes.

A primer on the polar vortex: https://t.co/U28GjWlVcN pic.twitter.com/L2ZI6FSrOl

— Amy H Butler (@DrAHButler) January 23, 2020

One key index that tells the tale of January is the Arctic Oscillation, which is based on the difference in surface pressure between lower and higher northern latitudes. When the AO is positive, the polar jet stream is typically stronger, more consistent, and further north, which keeps the coldest winter air locked in and near the Arctic.

Figure 1 shows that, from January 1 to 27, the AO has averaged above +2.0. According to NOAA, only four Januarys since 1950 have seen a positive AO this strong, including 1993 (+3.495), 1989 (+3.106), 1957 (+2.062), and 2007 (+2.034). Even if the AO weakens in the next few days, this month could end up with the third highest January value in 71 years of recordkeeping.

|

| Figure 1. Observed values for the Arctic Oscillation from October 1, 2019, to January 27, 2020. Shown in red at right are GFS ensemble-model projections for the AO extending out through early February. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPC. |

As is typically the case with a positive AO, the midlatitude jet stream has been noticeably consolidated as it circles the Northern Hemisphere. Storm systems have tended to be fairly weak across North America, leading to a fairly benign pattern for most of the contiguous U.S. When intense cyclones have developed, they’ve tended to be over the ocean, such as the one centered off the Canadian Maritimes a few days ago that led to record-burying snows in Newfoundland. Another intense cyclone is roiling the far North Atlantic this week, but it’s expected to weaken as the upper-level flow returns to a more zonal (west-to-east) configuration from the Atlantic into Europe, which has been having persistently mild conditions as well.

As of Sunday, Helsinki, Finland, had topped 5°C (41°F) on 15 days this month, which is almost twice the previous record number, according to Mika Rantanen (Finnish Meteorological Institute). The city is also having its least snowy year in nearly a century, and this month will likely be Helsinki’s first January in 176 years of recordkeeping in which every day reaches the freezing mark.

A persistent west-to-east jet stream also tends to lead to a mild pattern across the contiguous United States, and that’s exactly what we’ve seen thus far. Virtually the entire Lower 48 were warmer than usual for the month through January 25, and areas east of the Mississippi are running at least 6°F above average. Given the broad reach of mildness, it wouldn’t be a shock to see the entire contiguous U.S. ending up with one of its warmest Januarys on record, even if no single location has its all-time warmest January.

|

| Figure 2. Temperature departures from average for the contiguous United States for the period January 1-25, 2020. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPC. |

A major snow drought in Japan

The relentless zonal pattern has also kept cold-air masses from making their usual surges from Siberia into Japan. Temperatures topping 27°C (81°F) over the weekend approached the nation’s all-time January record. Hokkaido—the northernmost of Japan’s main islands, and one of the planet’s most reliably snowy places—has seen a mere pittance of snow so far this season compared to average. Hokkaido’s snowfall in December was 48 percent of average, the lowest in records going back to 1961, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency, as reported by This Week in Asia.

Sapporo, the capital city of Hokkaido and the site of the 1972 Winter Olympics, has received less than 60% of its typical snowfall to date. The city has been forced to import truckloads of snow ahead of the January 31 opening of its annual snow festival, reported the Japan Times.

Update (7 pm EST): Below are snow totals for the 2019-20 season through January 27 at prefectural (district) capital cities, as provided by the Japan Meteorological Agency. Note that 100 centimeters (one meter) is 39.4 inches.

Tottori: 0 cm (average 109 cm), 0% of average

Fukui: trace (average 137 cm), 0% of average

Kanazawa: 2 cm (average 1 cm), 2% of average

Toyama: trace (average 193 cm), 0% of average

Niigata: 1 cm (average 104 cm), 1% of average

Nagano: 20 cm (average 128 cm), 16% of average

Yamagata: 26 cm (average 216 cm), 12% of average

Akita: 41 cm (average 194 cm), 21% of average

Aomori: 168 cm (average 378 cm), 44% of average

Sapporo: 177 cm (average 315 cm), 56% of average

For noteworthy chill, try Alaska

The land area north of the equator with the most consistent cold this month has been Alaska. Even with a monthly average so far of –20.9°F in Fairbanks, this won’t be the city’s coldest January on record, and perhaps not even among the top ten coldest. In January 1906, the average for January was –36.4°F. However, there’s been no real relief in the cold, according to Rick Thoman (University of Alaska Fairbanks). The city has failed to get above 4°F thus far in January, and that mark looks unattainable through the end of the month, with the city expected to remain well below –10°F through the next week. Every other January has gotten up to at least 5°F in Fairbanks at least once, Thoman noted in a tweet.

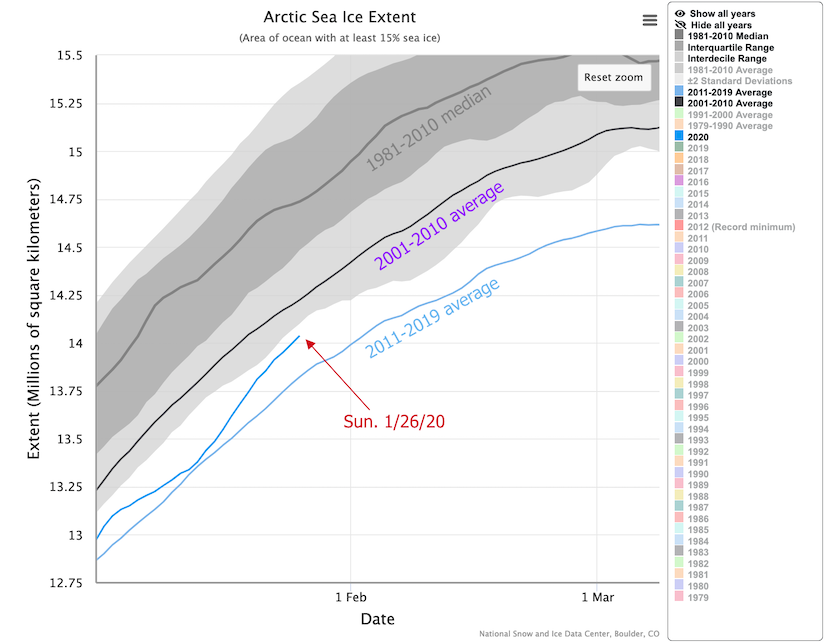

One bright spot in the relentless far-north chill: it’s given sea ice a chance to make at least a minor recovery, although the long-term outlook for Arctic sea ice in a warming world remains grim. The Arctic’s sea ice extent as of Sunday was well above the average for the date in the 2010s, but well below the average from the 2000s and prior decades.

|

| Figure 3. Sea ice extent in the Arctic Ocean as of Sunday, January 26, compared with the average for the two prior decades and the 1981-2010 mean. Image credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center. |

Bering Sea #seaice extent from @NSIDC is slowly increasing, but remains below the long term average & last year. But extent isn't everything. Sustained cold weather near the Alaska coast since mid-Dec helping to thicken and stabilize nearshore ice. #akwx #Arctic @Climatologist49 pic.twitter.com/3rt7CPX38Z

— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) January 26, 2020

What next?

Forecast models are hinting that the jet stream will dip further into the United States in early February, starting off with a potential East Coast coastal storm (although there’s still great uncertainty as to how this system will evolve). Both NOAA and The Weather Company are predicting a good chance of colder-than-average conditions in February to infiltrate areas from the Northern Plains and Midwest to New England .

Alas, this pattern shift may leave California high and relatively dry. The persistent westerlies have been focused on the Pacific Northwest in recent days, resulting in feet of snow in the Cascades and flood/mudslide threats at lower elevations. High pressure may strength along the west coast in early February, further reducing the chance of generous rains and mountain snows in California. As of Monday, the water content of the state’s crucial Sierra snowpack was running well below average.

High likelihood of broad high pressure ridge over NE Pacific that will keep much of California mostly dry for the next 10-14 days, with well below average precip and well above average temperatures at what is typically wettest/coolest part of year. #CAwx pic.twitter.com/cyhnDPD8vD

— Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) January 27, 2020

Thanks to climate researchers Yusuke Uemura and Maximiliano Herrera for assistance with the Japan statistics in this article.