| Above: Brian Nutchler walks through floodwater to his home on March 22, 2019, in Craig, Missouri. Midwest states battled some of the worst flooding they have experienced in decades as rains and snowmelt associated with a massive mid-March storm inundated rivers and streams. Image credit: Scott Olson/Getty Images. |

With a few regional exceptions, March was on the cool side for much of the contiguous U.S., according to analyses released by NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Information on Tuesday. The average temperature for March (40.68°F) was the 44th coolest in 125 years of recordkeeping, running 0.82°F below the 20th-century average.

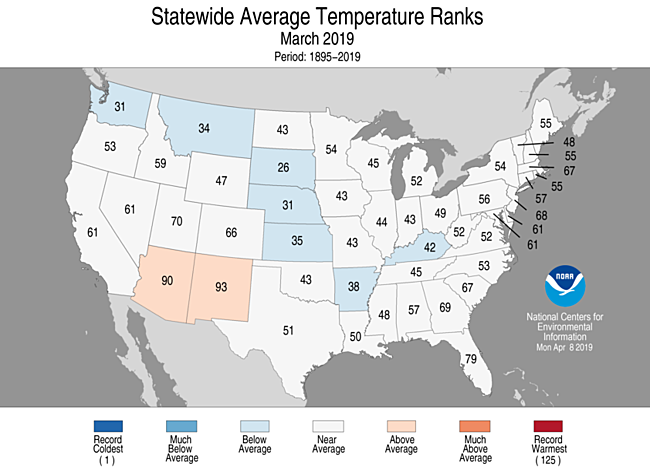

Although March brought some dramatic local temperature swings—par for the course in what’s historically the most extreme month of the year (see Chris Burt’s recap of March weather madness)— the variations got smoothed out enough during the course of the month to keep any state from having a top-30 warmest or coolest March. Only two states were significantly warmer than average (Arizona and New Mexico), and a winding corridor of seven states from Washington to Kentucky was significantly cooler than average (see Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Statewide rankings for average temperature for March 2019, as compared to every March since records began in 1895. Darker shades of red indicate higher rankings for heat, with 1 denoting the coldest month on record and 125 the warmest. Image credit: NOAA/NCEI. |

The year to date (January-March) is running just below average, as the 61st coldest in 125 years of recordkeeping. The last time that the contiguous U.S. got off to this cool of a start was in 2014.

The unusual chill has been focused on the Northern Plains and Upper Midwest, while most of the Sun Belt has leaned milder than average. In South Dakota, the year thus far is the 16th coldest on record, while in Florida this is the 9th warmest year on record so far.

The bulk of the heartland cold in 2019 unfolded during February and March, ushered in by the “polar vortex” outbreak at the end of January. It was the nation’s 35th coldest February-March on record, and the coldest since 1989. Large parts of the north central U.S. had their coldest February-March in decades (it was Denver’s chilliest since 1965), and in much of Montana, it was the coldest such period on record. Below is a summary of some of the local highlights, along with the periods of record (POR):

City Feb-Mar 2019 avg Last time colder

Billings MT 19.4°F (coldest) none, POR 1935- (old record 19.9°F in 1936)

Bozeman MT 13.5 °F (coldest) none, POR 1942- (old record 14.4°F in 1979)

Missoula MT 23.0 °F (coldest) none, POR 1894- (old record 23.7°F in 1936)

Helena MT 14.2°F (coldest) none, POR 1939-; old record 17.3°F in 1989)

Williston ND 10.3°F (5th coldest) 6.5°F in 1936, POR 1894-

Fargo ND 10.7°F (11th coldest) 10.0°F in 1979, POR 1881-

Scottsbluff NE 26.8°F (6th coldest) 26.5°F in 1965, POR 1893-

Omaha NE 27.0°F (12th coldest) 24.8°F in 1979, POR 1871-

Denver CO 31.7 (12th coldest) 28.2°F in 1965, POR 1872-

For #Alaska, #March 2019 exceeded previous warmest March avg temperature record set in 1965 by more than 3°F: @NOAANCEIclimate https://t.co/1YI9XVPPbq #StateOfClimate pic.twitter.com/LOKRkJEJ03

— NOAA (@NOAA) April 9, 2019

A spring fever spikes across Alaska

The most extreme temperature departures for the month by far were in Alaska, where persistent southerly flow pushed monthly averages to unprecedented highs. Both Anchorage and Fairbanks had their warmest March on record, but the most astounding departures were across northern and western Alaska. Kotzebue ended the month with an average temperature of 23.0°F, which is 7.4°F above the city’s previous monthly record (set in 1898) and a full 21.9°F above the monthly average (1981-2010). Utqiaġvik (Barrow) smashed its March record by 5.5°F, and Bethel, Nome, and Delta Junction beat their previous warmest March average by more than 1°F.

A new paper shows that air temperature is the “smoking gun” behind climate change in the Arctic, according to John Walsh, chief scientist @IARC_Alaska.@UAFGI https://t.co/uoxms7q00n pic.twitter.com/uWvDlfMgtB

— IARC Fairbanks (@IARC_Alaska) April 8, 2019

A surprisingly dry month for the nation as a whole

March was a paradoxical month for moisture. After excessive autumn rains in many areas, followed by the wettest winter in U.S. history, the nation’s landscape entered the month in an uncommonly moist state. Catastrophic flooding hit the Midwest in mid-March (see discussion below).

By March 26, the percentage of the nation covered by severe, extreme, or exceptional drought (levels D2-D4) was down to 0.86%, which is the lowest weekly value in the entire 19-year history of the U.S. Drought Monitor.

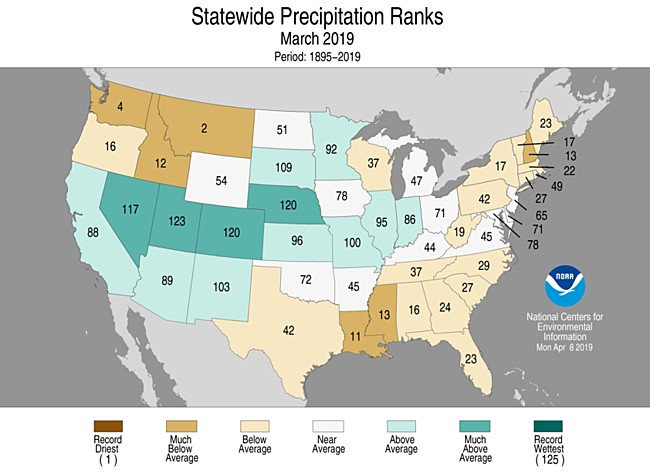

Even so, much of the contiguous U.S. was drier than average in March. In fact, it was the nation’s 34th driest March on record, with much-below-average precipitation affecting a grab bag of states from the Pacific Northwest to the Mississippi Valley to New England. Montana had its second driest March, and Washington its third driest. Four states saw a top-ten-wettest March: Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Nebraska.

|

| Figure 2. Statewide rankings for average precipitation for March 2019, as compared to every March since records began in 1895. Darker shades of green indicate higher rankings for moisture, with 1 denoting the driest month on record and 125 the wettest. Image credit: NOAA/NCEI. |

|

| Figure 3. Floodwater covers Highway 2 on March 23, 2019, near Sidney, Iowa. Image credit: Scott Olson/Getty Images. |

The $4+ billion cyclone

Without doubt, the weather highlight of the month for the contiguous U.S. was the intense “bomb cyclone” that ramped through the central U.S. on March 12-14. Dubbed Winter Storm Ulmer by the Weather Channel, the storm produced a cavalcade of record-smashing phenomena and destructive impacts. Between the storm and two weeks of subsequent flooding, total economic losses were estimated by insurance broker Aon at more than $4 billion, with up to $1 billion in public and private insurance claims (see PDF of Aon’s Global Catastrophe Recap for March).

Strong southerly flow ahead of the cyclone pushed warm, moist air atop snow-covered ground, leading to heavy rain that unleashed massive amounts of water in snowpack. Great chunks of ice jammed rivers, and levees gave way, leading to catastrophic flooding along and near the Missouri River, especially across eastern Nebraska and western Iowa. More than 40 locations set all-time record-high flood crests, mainly in those two states, according to weather.com.

Trooper Viterna #480 standing next to ice chunks from the Niobrara River that were left behind after causing all kinds of damage. pic.twitter.com/nVWf5yUe12

— NSP Troop B Nights (@NSPTroopBNights) March 20, 2019

At the center of the cyclone, mean sea level pressure (MLSP) plummeted to 970.4 mb at Lamar, Colorado. “I can't find evidence of a lower pressure…in Colorado in the past records,” tweeted state climatologist Russ Schumacher. Denver also set its all-time MSLP record, with 979.01 mb, as noted in weather.com’s storm roundup.

The extreme pressure contrast drove extreme winds across the region, leading to blizzard conditions to the north and west of Ulmer and wind damage and blowing dust toward the south. A wind gust of 80 mph at Denver was the city’s strongest non-thunderstorm-related gust on record, and gusts to 96 mph were reported at Colorado Springs.