| Above: A sprawling upper-level low across the western U.S., ringed by winds at the jet-stream level topping 120 mph, will envelop a surface low predicted to bring fierce weather across the Plains and Upper Midwest. Shown here are winds at the 250-millibar level (about 34,000 feet) predicted for 12Z (7 am CST) Friday, April 12, by the 12Z Wednesday morning run of the GFS model. A slowly weakening surface low is predicted to be in southern Minnesota by this point. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

Much like the infamous “bomb cyclone” of mid-March, another intense storm wrapped up across the central Plains from Wednesday into Thursday, bringing widespread blizzard conditions to its north and threatening snowfall and low-pressure records for April. Some locations may break all-time records for any two-day snow event.

Dubbed Wesley by the Weather Channel, the surface storm had already met the definition of a meteorological bomb on Wednesday morning when adjusted for latitude (see discussion below). Wesley organized in eastern Colorado ahead of a powerful upper-level trough sweeping through the Rockies and intensified as it drifted into Kansas. Models called for the surface low to gradually weaken as it heads across Iowa and Wisconsin by Friday.

While this storm did not reach the depths of low pressure attained by the March storm, it’ll still pack a formidable punch. A cold surface high nosing in from central Canada will keep surface temperatures cold enough to support snow, as rich moisture flows into the storm from just above the surface and converges along a frontal zone extending northeast from the surface low. Snowfall rates of 1” to 3” per hour could occur, especially in the peak snow zone across eastern South Dakota and southwest Minnesota.

On the forward flank of Wesley, snowfall had already totaled 10”-12” over parts of South Dakota as of Wednesday morning. “Heavy snow is reducing visibility to just a few feet and roads are becoming impassable,” warned the sheriff’s offices of Hamlin and Deuel counties in South Dakota at midday Wednesday.

|

| Figure 1. Snowfall reports compiled by the NOAA/NWS Weather Prediction Center during the 24 hours ending around 1 pm CDT Thursday, April 11, 2019. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/WPC |

Update (April 11): Heavy snow continued to fall at midday Thursday from western Nebraska to Minnesota. According to weather.com's Jonathan Belles, at least one town experienced a "thunderblizzard"—Watertown, SD—as thunder and lightning accompanied conditions that met the NWS definition for a blizzard: considerable falling or blowing snow, winds in excess of 35 mph, and visibilities of less than 1/4 mile for at least 3 hours.

US HWY 81 near Mile Marker 87. Lake County SD, W of Madison. As you can see road conditions are poor. Slippery roads and strong winds causing problems. Heavy duty wrecker on scene. Use caution! #keepSDsafe pic.twitter.com/PEO6CnKedf

— SD Highway Patrol (@SDHighwayPatrol) April 11, 2019

Fierce winds feeding into the storm were making travel difficult or impossible even in areas where snowfall totals are on the lighter side. Blizzard warnings were in place on Wednesday morning for parts of six states, extending from the Denver area to just west of Minneapolis. Freezing rain could pelt some parts of southeast Minnesota and western Wisconsin. Lightning and thunder will accompany the snow and ice at some locations. Update (March 11): Thundersnow has been widespread across eastern South Dakota and southwest Minnesota, as shown in the embedded tweet below.

Lots of #thundersnow 2 days in a row #sdwx #mnwx pic.twitter.com/XKqGT2naZN

— Stu Ostro (@StuOstro) April 11, 2019

A small crop of fast-moving severe thunderstorms moved across far northeast Kansas and eastern Nebraska late Wednesday. Update (April 11): Severe weather turned out to be minimal on Wednesday, according to the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center, with 18 reports of severe hail (two up to golf ball size) and just 3 reports of high wind. Another round of severe weather is expected across Illinois and Indiana on Thursday ahead of Wesley’s cold front.

Meanwhile, hot, dry winds swept across the Southern Plains on the south side of Wesley. SPC tagged parts of southeast New Mexico and far west Texas with an extremely critical fire weather rating (the most dire category) for Wednesday. Update (April 11): A 1000-acre wildfire erupted Wednesday near Portales, NM, destroying four buildings and sending one person to the hospital with smoke inhalation. The fire was under control as of Wednesday night. Widespread blowing dust that was kicked up across the Southern Plains on Wednesday wrapped into the core of Wesley, giving the snowfall in Minneapolis a dusty tinge.

Have you noticed a tan or orange tint to the snow this morning? If so, the color is likely due to dust that was blown by high winds all the way from west Texas. Here's a satellite image from yesterday showing the blowing dust in west Texas heading NE. #mnwx #wiwx #txwx pic.twitter.com/RIlauFnE3g

— NWS Twin Cities (@NWSTwinCities) April 11, 2019

Records at risk

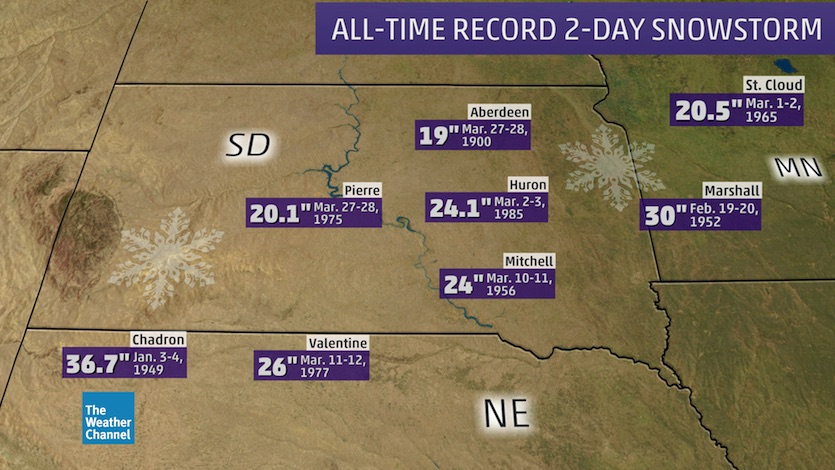

Computer models are projecting immense amounts of snow for parts of eastern South Dakota and southwest Minnesota. The expected peak storm totals of 16” to 24”—with local amounts possibly even higher—could jeopardize all-time two-day snowfall records, according to weather.com’s Brian Donegan. Based on NOAA data, some locations that could see their heaviest two-day snowstorm on record include Aberdeen, Huron, Mitchell and Watertown in South Dakota and Marshall and Redwood Falls in Minnesota.

|

| Figure 2. All-time two-day snowfall records for the Midwest. |

Given the mid-April timing, it’s quite possible that snow on the ground won’t pile up to the level indicated by the models. As the snow falls, the relatively warm ground may melt some snow from below, while filtered sunlight could trim the snowpack from above. Official snowfall measurements are taken at regular intervals using snowboards, so the sum of these measurements often exceeds the ground cover with late-season storms like this.

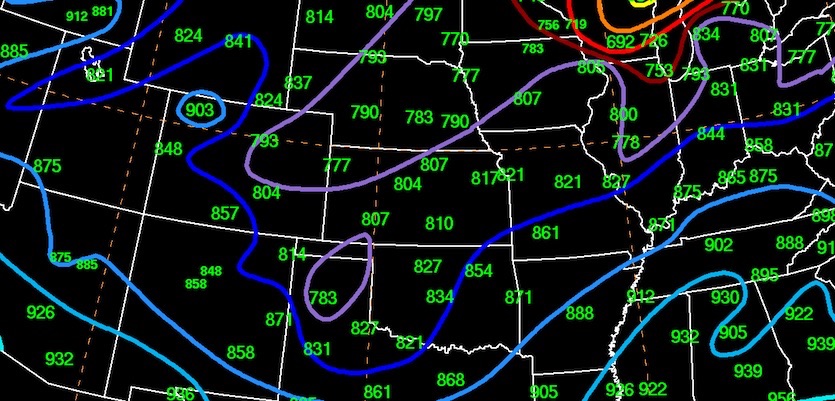

The surface low with this week’s cyclone could also set April records for low pressure at several points, especially in Kansas. Models agree that the surface low will deepen to the neighborhood of 980 mb by Wednesday night. Update (April 11): The storm bottomed out with a central pressure of 982 mb, just shy of the depth needed to set April records.

|

| Figure 3. All-time surface low pressure records for April in the central U.S., expressed in millibars and tenths of millibars with the first “9” omitted. For example, 807 at Dodge City, Kansas, corresponds to a record April low pressure of 980.7 mb. Image credit: David Roth, NOAA/NWS/WPC. |

Is this week’s storm really a bomb cyclone? It’s complicated

On Tuesday, multiple national news sources were already referring to this week’s major storm as a “bomb cyclone,” keying off its similarity to the system of mid-March. A relative newcomer to the public, the phrase is a natural for social media, much like “polar vortex”. It’s vivid, concise, and evocative, and it certainly conveys a sense of gravity.

There’s a widely used definition for what constitutes a meteorological “bomb”—and then there’s what we might call a stealth definition, one tucked away in the 39-year-old research paper from which the term originates. Fred Sanders and John Gyakum, both from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote the 1980 paper, “Synoptic-Dynamic Definition of the ‘Bomb’,” for the AMS journal Monthly Weather Review. (Note that “bomb cyclone” is inherently redundant, since “bomb” is defined as a type of cyclone.)

Sanders and Gyakum start off the paper with the first definition, which many weather enthusiasts already know:

“Tor Bergeron is reputed to have characterized a rapidly deepening extratropical cyclone as one in which the central pressure at sea level falls by at least 1 mb/hr for 24 hours.”

The catch, according to Sanders and Gyakum, is that Bergeron’s definition most likely applied to storms at the latitude of his research home base—the University of Bergen, Norway—which happens to be located at 60°N. Extratropical (nontropical) cyclones tend to be more intense at higher latitudes and weaker at lower latitudes. Thus, Sanders and Gyakum suggested that the definition of a meteorological bomb should be latitude-dependent, with the deepening rate at a given spot multipled by sin(latitude)/sin(60°N)). This means a cyclone doesn't have to deepen as much at lower latitudes in order to qualify as a bomb.

The mid-March storm was clearly a meteorological bomb no matter how you slice it, as it deepened by 24 mb in just 11 hours at latitudes between about 35°N and 40°N. This week’s cyclone didn't deepening 24 mb in 24 hours, but would it still qualify? David Roth, head of the NOAA/NWS Weather Prediction Center, issued the verdict in a tweet on Wednesday morning: yes indeed.

The CO low’s central pressure has fallen to 988 hPa at 1500 UTC. Since its pressure has dropped from 1005 hPa at 1800 UTC yesterday, and the bomb equation calculates 17 hPa fall in 24 hours as satisfying criteria at 38N, the CO low has met bomb criteria with 3 hours to spare. pic.twitter.com/uq1u7Jx96y

— David Roth (@DRmetwatch) April 10, 2019