| Above: A school bus makes its way on the flooded Hopper Road in Houston on September 19, 2019 in Houston, Texas. Gov. Greg Abbott declared much of Southeast Texas disaster areas after heavy rain and flooding from the remnants of Tropical Depression Imelda dumped more than two feet of water across some areas. Image credit: Thomas B. Shea/Getty Images. |

Tropical Depression Imelda has dissipated after producing disastrous floods across southeast Texas, especially from late Wednesday into Thursday, in a belt stretching from near Beaumont to northern parts of the Houston area. Two people were killed and hundreds were rescued, according to weather.com. The largest storm totals for Imelda from 7 am CDT Monday through 10 am CDT Friday, as reported by the NOAA/NWS Weather Prediction Center, were:

43.39” at North Fork Taylors Bayou

42.76” at Mayhaw Bayou @ Brush Island Road

40.98” at Green Pond Gully

The highest 3-day rainfall amounts at WU personal weather stations from Tuesday through Thursday:

39.69” at North Cleveland

36.70” at Beaumont

The peak of 43.39" at North Fork Taylors Bayou puts Imelda fifth among the heaviest single-point rain producers among all tropical cyclones on record in the contiguous United States, as noted by Capital Weather Gang.

Reflecting on #Imelda: This short-lived "weak" tropical storm has now unloaded nearly 44 inches of rain in Southeast Texas. It is among the top 5 wettest tropical systems to ever to hit the Lower 48. Our detailed write-up on it is here: https://t.co/ox6wzPphUa (1/x) pic.twitter.com/HyPEju2PdJ

— Capital Weather Gang (@capitalweather) September 20, 2019

Beaumont (City Station) recorded 19.80” on Thursday, the largest calendar-day total by far in that site’s 118-year history. The runner-up is 14.50” on August 30, 2017, during Hurricane Harvey. Houston had its wettest September day on record Thursday, with 9.21” falling at Bush Intercontinental Airport. This is the fifth wettest calendar day in Houston records dating back to 1888. Amazingly, four of the city’s six wettest days have been in the last three years:

16.07” August 27, 2017 (Harvey)

10.34” June 26, 1989

9.92” April 18, 2016

9.25” October 25, 1984

9.21” September 19, 2019 (Imelda)

8.37” August 26, 2017 (Harvey)

Here's the four-day comparison of rainfall between Harvey (L) and #Imelda (R). Harvey's intense rains continued into day 5. Meanwhile, disorganized diurnal showers will likely add only small amounts to the "Imelda event" totals into this weekend. pic.twitter.com/5PhXYpvNkh

— Greg Carbin (@GCarbin) September 20, 2019

Development and climate change are making heavy rains and flooding worse in southeast Texas

Even though Imelda's rains were well short of Harvey's in terms of area covered and peak amounts, as shown above, they still caused massive disruption in one of the nation's major population centers. Houston’s vulnerability to flooding is legendary—an unhappy product of frenzied development, a location naturally prone to extreme rainfall events, and a climate being changed by human activity. Climate change is leading to heavier extreme rains as well as slower-moving tropical cyclones, as we'll discuss in a forthcoming post. It is exceptionally difficult to sort out exactly how much of Houston's increased flooding can be chalked up to climate change versus development patterns, but there is no doubt that the region's most intense rains are getting even more intense.

Aon meteorologist Steve Bowen put it this way in a tweet: “Increased frequency of high-end "tail" rainfall & flood events. Explosive population growth. Soil type unable to absorb excess water. Concrete haven. Changing terrain. Flood mitigation & larger scale disaster planning is crucial in #Texas. This known risk not going away.”

Imelda puts an exclamation point on the fact that the heaviest rains in many parts of the world, including many parts of the United States, are getting heavier—a conclusion that meshes with human-induced climate change, which puts about 4% more water vapor in the air for every 1°F rise in temperature. The upward trend in rainfall extremes has been confirmed through multiple studies in the past 20 years and reiterated in IPCC assessments. In the United States, the region with the biggest increase from 1948 to 2015 in the amount of autumn rain (September-November) one would expect to fall in a once-every-20-year event has been the Southeast, with a 41% jump, according to the 2017 Climate Science Special Report from the U.S. National Assessment.

Out of 244 cities analyzed by Climate Central in 2018, the location with the greatest increase in the amount of rain falling on the wettest calendar day of the year was Houston. The linear trend from 1950 to 2018 shows a rise of 2.78”, almost doubling the amount of rain falling on each year’s wettest day. This result is skewed in part by the massive rains from Harvey in 2017, but most years since 2000 have seen at least one 4” day, whereas most years in the 1950s failed to have even one 4” day.

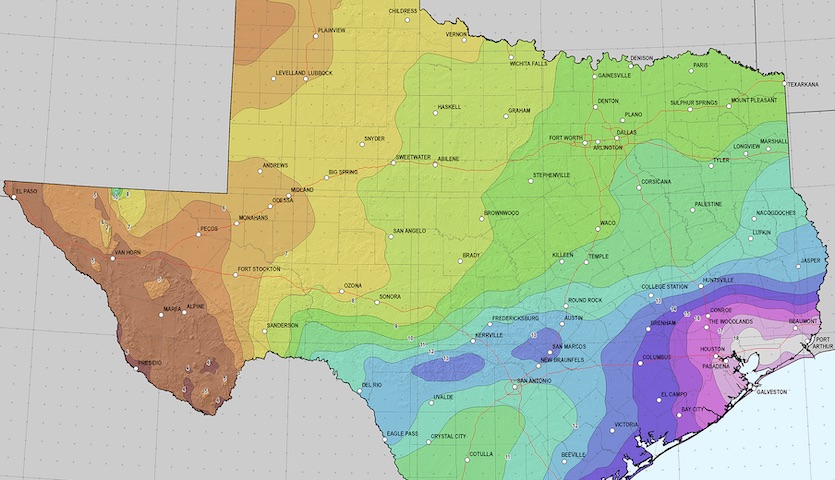

In southeast Texas, 10- and 100-year flood values increased in a 2018 statewide update to NOAA’s Precipitation-Frequency Atlas of the United States, also known as “Atlas 14.” The amount of rain in an event one might expect to occur every 100 years in Houston has increased from around 13 to around 18 inches, and the recurrence interval for a 13-inch rain has dropped from about once every century to about once every 25 years. The previous Atlas 14 values for Texas were based on calculations done in the 1960s and 1970s, so they did not reflect the “new normal” of our human-altered atmosphere. According to NOAA, the new values also reflect improved analysis methods and an increase in available data, due to more rain gauges and gauge networks.

|

| Figure 1. Storm-total rainfall amounts that would be expected to occur about once every 100 years across parts of Texas, as calculated for the 2018 update of the NOAA Atlas 14 document. Image credit: NOAA. |

Climatological averages for temperature and precipitation are updated every decade by NOAA/NWS based on the preceding 30-year period. The current norms are based on the period 1981-2010; early in the 2020s, these will be updated to reflect 1991-2020 values. Flood “recurrence intervals” are different, because they have to provide guidance on events that happen too infrequently to show up in a 30-year climatology. These values are instead calculated based on research into how quickly the frequency of heavy rain drops off for larger amounts of rain.

The Atlas 14 values for most states have been updated in the past few years, although values for the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies still date as far back as the 1970s.

Colorado state climatologist and precipitation expert Russ Schumacher observed on Twitter that the United States saw just two events east of the Rockies between 2001 and 2015 that produced at least 600 mm (~23.6 inches) of rain over 3 days. From 2016 to 2019, there has been one such event in each year. He concludes: "If it's a trend (and there are certainly reasons to believe it is), it's not a good one."