| Above: Hurricane Lane as viewed from the International Space Station early Wednesday morning, August 22, 2018, when it was roiling the central Pacific as a Category 5 storm. Image credit: Ricky Arnold/NASA, @astro_ricky. |

Hurricane warnings were extended on Wednesday evening from the Big Island through Oahu, including Honolulu, ahead of formidable Hurricane Lane. Still a powerful Category 4 storm, Lane was packing top sustained winds of 145 mph at 8 pm HST Wednesday (2 am EDT Thursday). Lane’s center was located about 260 miles south of Kailua-Kona and about 375 miles south-southeast of Honolulu. The storm’s long-awaited right turn was under way, as Lane was moving northwest at 7 mph.

All of Hawaii’s major islands were under a hurricane warning late Wednesday except for Kauai and Niihau, which were under a hurricane watch. Lane appears to be the first storm to put virutally the entire state of Hawaii under hurricane watches and/or warnings, and it marks only the second time Honolulu and Oahu have been in a hurricane warning. The other time was during Iniki (1992), which ravaged Kauai as a Category 4 storm. Iniki stayed far enough west to spare Honolulu from sustained hurricane-force winds.

“Regardless of the exact track of the storm center, life-threatening impacts are likely over some areas as this strong hurricane makes its closest approach,” warned the National Weather Service office in Honolulu in a Hurricane Local Statement on Wednesday evening.

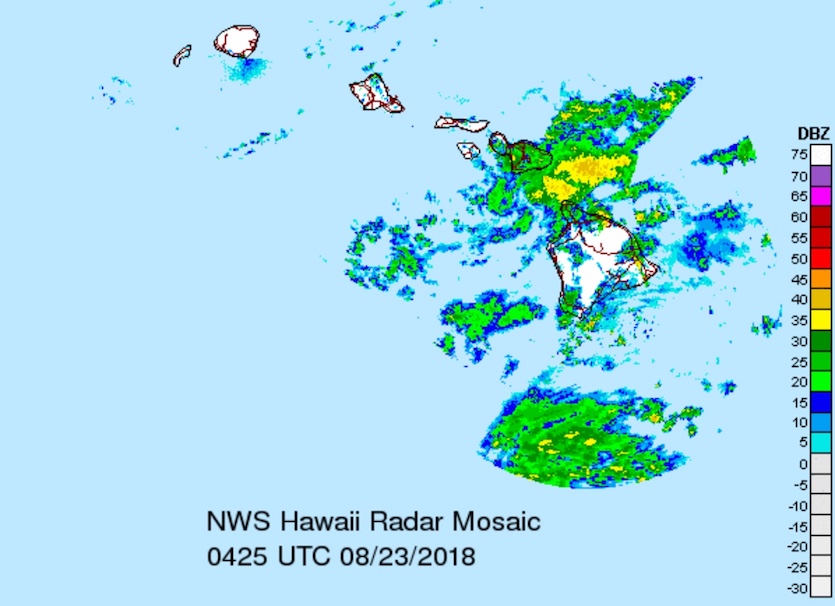

|

| Figure 1. Lane’s outer rainbands were sweeping northward across the Big Island and Maui late Wednesday, August 22, 2018. See this link for extended radar animations. Image credit: Courtesy Brian McNoldy, University of Miami/Rosenstiel School. |

Models continued to agree on Wednesday evening that Lane will head north to north-northwest, remaining a major hurricane through Thursday night, then angle sharply westward on Friday as wind shear takes an increasing bite out of the storm’s strength. As of Wednesday night, the southwesterly upper-level flow ahead of Lane appeared to be enhancing the storm’s outflow rather than denting its strength. Based on the 0Z Thursday run of the SHIPS model, it may be Thursday afternoon or evening before wind shear begins to have a major detrimental effect on Lane.

What remains most uncertain is exactly how far east Lane’s center will get before the turn, and how far north its westward course will be. The main wild card is the possibility that the higher terrain of the Big Island and Maui will induce enough low pressure to the west of those two islands to pull Lane closer toward them, perhaps leading to a temporary north-northeast motion on Friday and a closer encounter with Maui and the northermost Big Island. This scenario would be in line with recent runs of the GFS, HWRF, and UKMET models—but not with the European (ECMWF) model, which has consistently kept Lane much further from the Big Island and Maui. Although the ECMWF is often the best-performing individual model, this is not always the case, just as a top-rated baseball team doesn’t win every game. If a more rightward track comes to pass—i.e., a path near the right-hand side of the cone in Figure 2—then the impacts could be considerably greater for the northern Big Island and Maui.

The National Hurricane Center’s consensus of top models typically beats any individual model, and the official consensus-based forecast shown in Figure 2 is still the most likely outcome as of Wednesday night, but Lane must be watched closely for any hint of a north-northeast bend late Thursday into Friday.

|

| Figure 2. Forecast track and “cone of uncertainty” for Lane as of 5 pm HST (11 pm EDT) Wednesday, August 21, 2018. The cones are constructed based on typical forecast errors over the past few years such that a hurricane can be expected to fall within the cone about two-thirds of the time. The cone suggests that Lane’s center will most likely remain well south and west of each Hawaiian island. However, Lane’s effects will extend far from its center, touching virtually all of the islands in some form or fashion. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPHC. |

Lane’s greatest threat: floods and mudslides

Even if Lane doesn’t strike any of Hawaii’s islands directly, it could still be a catastrophic hurricane. Lane’s powerful and well-established circulation will send huge amounts of tropical moisture flowing against the islands’ rugged terrain. The hurricane will also continue to slow down as it nears the islands, especially on Friday. This will lead to periods of torrential rain that could extend over several days in the most favored spots, especially across north- and east-facing slopes.

Totals of 10” - 15” can be expected across many parts of Hawaii, and I would not be at all shocked to see a few localized amounts well above 30”, especially along east-facing slopes of the Big Island and Maui. Massive flows from these rains could lead to floods, landslides, and road washouts. Rainfall records for August may fall in a number of locations, including Honolulu and Lihue.

Among the potential impacts noted by NWS/Honolulu in its Hurricane Local Statement on Lane:

- Extreme rainfall flooding may prompt numerous evacuations and rescues.

- Rivers and tributaries may overwhelmingly overflow their banks in many places with deep moving water. Small streams, creeks, canals, arroyos, and ditches may become raging rivers. In mountain areas, deadly runoff may rage down valleys while increasing susceptibility to rockslides and mudslides. Flood control systems and barriers may become stressed.

- Flood waters can enter numerous structures within multiple communities, some structures becoming uninhabitable or washed away. Numerous places where flood waters may cover escape routes. Streets and parking lots become rivers of raging water with underpasses submerged. Driving conditions become very dangerous. Numerous road and bridge closures with some weakened or washed out.

|

| Figure 3. The probability of experiencing tropical-storm-force winds (sustained at 39 mph or more) at some point between Wednesday afternoon, August 22, 2018, and Monday afternoon, August 27, based on the forecast track as of Wednesday afternoon. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPHC. |

Wind and tornado threat from Lane

The chance of sustained hurricane-force winds would be very low if Lane stayed well to the left of each island. However, the risk of tropical-storm-force sustained winds (39-73 mph) would remain quite high. Nearly all locations except for the easternmost part of the Big Island have a greater-than-even chance of experiencing such winds. As Lane weakens, its wind field will spread out, so that it could continue to pack sustained winds of 40 - 55 mph as far as 100 miles north of its center through at least Saturday. Such winds can be enough to bring down trees and power lines, especially after soils are saturated by heavy rain.

The strongest wind gust on record for Honolulu is 82 mph, recorded as Category 1 Hurricane Nina (1957) approached from the south and then veered west just in the nick of time. If Lane passed over or near Oahu as a minimal Category 1 hurricane, or even as a high-end tropical storm, it could still deliver a wind gust of 83 mph and sustained winds of 50 mph or greater. The population of Oahu and Honolulu has nearly doubled since Nina delivered its record 82-mph gust, and there are many more people living and working in high-rise buildings, where winds can be considerably stronger than at ground level.

Tornadoes are somewhat more likely with Lane than with Hawaii’s other recent brushes with tropical cyclones, in part because of the storm’s strength and path. As it approaches, Lane will put each island in its right front quadrant, the most favored location for the wind shear that can lead to tornadoes. On average, Hawaii sees less than one tornado a year, with 42 recorded from 1955 to 2015, according to the Tornado History Project. Most of these occurred in association with winter storms rather than tropical cyclones. Four of Hawaii’s tornadoes have been rated F2, the most recent being on May 18, 1982.

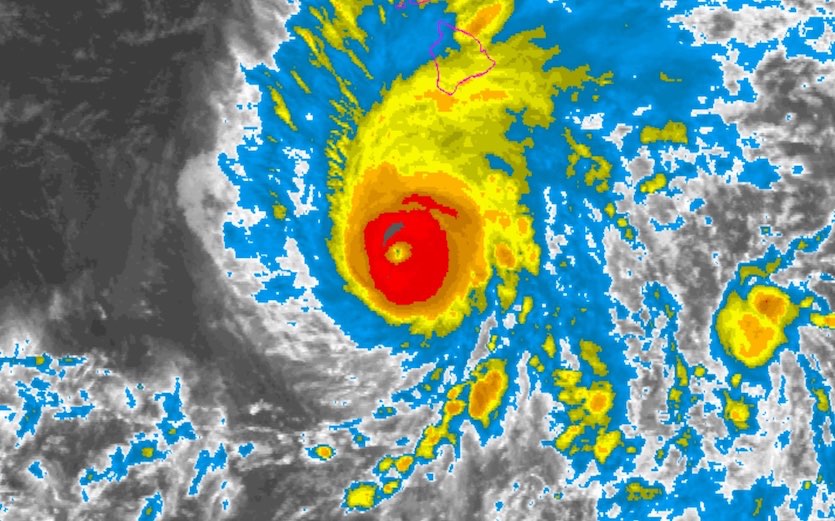

|

| Figure 4. Infrared image of Hurricane Lane at 0500Z Thursday, August 23, 2018 (7 pm HST Wednesday or 1 am EDT Thursday). Image credit: NOAA/NESDIS. |

Storm surge: a lesser concern

Storm surge is generally less of a threat in Hawaii compared to Atlantic hurricanes hitting the U.S. coast, since the Hawaiian Islands are surrounded by deep water that prevents a storm surge from building to large heights. The worst-case surge from a mid-strength Category 2 hurricane hitting Oahu, for example, is only four feet in Pearl Harbor, which is the most vulnerable portion of Oahu to storm surge (see wunderground’s Maximum of the "Maximum Envelope of Waters" (MOM) storm tide image).

A bigger threat than the storm surge is the waves Hurricane Lane will generate. The latest marine forecasts for the leeward waters of the Big Island and Maui call for waves of up to 22 feet at the peak of the storm.

What about Kilauea?

Experts say there's little risk that the effects of the hurricane will make things worse at the Kilauea volcano on the Big Island, where hundreds of homes have been lost from this summer's lava flows. "Effects of hurricane-related torrential rainfall on the lower East Rift Zone lava flow will be minimal," Janet Babb, a geologist at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, told weather.com. "Where the interior of the flow is still hot, heavy rain will likely result in the formation of steam."

For more details on potential impacts from Lane, see the frequently updated weather.com feature story.

Dr. Jeff Masters contributed to this post.