| Above: A commuter arrives at Metra Western Avenue station, Tuesday, Jan. 29, 2019, in Chicago. Temperatures at O'Hare International Airport dipped below 0°F between 6 and 7 am CST Tuesday, and they are expected to stay below zero through Thursday. Wednesday could produce the lowest daily high in Chicago weather records that date back to 1872. Image credit: AP Photo/Kiichiro Sato. |

An Arctic invasion is underway in the Midwest U.S., where the coldest airmass in years is settling in and will remain entrenched Tuesday through Thursday. Accompanying the cold air will be strong westerly winds of 10 - 20 mph that will generate very dangerous wind chills below -40°F in portions of 12 states. It is extremely unusual for cold this intense to be accompanied by winds this strong, and people venturing outdoors into the cold should take the threat of frostbite very seriously. The potential exists for some states to experience their coldest wind chill readings ever recorded.

At 11 am CST Tuesday, the NWS office in Grand Forks, North Dakota, reported a temperature of –25°F with a wind gust to 44 mph, resulting in a wind chill of –61°F. As shown in the tweet below, this is only a few degrees above the lowest wind chill on record in the contiguous U.S.

Here's what I was able to find for lowest wind chills for selected states based on hourly observations from all stations available at the Iowa State Mesonet site. All of these use the "new" (2001) formula. pic.twitter.com/3ll1Pt711f

— Brian Brettschneider (@Climatologist49) January 28, 2019

As detailed in our previous post, the current cold blast has not set any all-time record lows at any major stations with a long-term period of record thus far, though several stations in northern Ontario have come within a few degrees of doing so. At least four Midwest U.S. cities have a chance of setting an all-time cold record Wednesday or Thursday morning, though: Chicago (predicted low, –24°F, record low, –27°F); Rockford, Illinois (predicted low –31°F, record low –27°F); Cedar Rapids, Iowa (predicted low –32°F, record low –29°F); and Waterloo, Iowa (predicted low, –26°F, record low, –34°F).

Because the intense cold will be sustained over two to three days, the odds will be boosted for daily and all-time record-cold maxima. The all-time lowest daily highs at Chicago (-11°F on Jan. 18, 1994 & Dec. 24, 1983) and Rockford (-14°F on Jan. 18, 1994, and Jan. 6, 1912) are both in jeopardy. For Wednesday, Weather Underground is predicting highs of -12°F in Chicago and -14°F in Rockford. The high temperature for the day will likely come at midnight, since cold Arctic air will be pouring into the region during the day. For a more detailed analysis of the potential records from this cold wave, see the latest weather.com write-up.

|

| Figure 1. Wind chills predicted by The Weather Channel for Wednesday morning, January 30, 2019, as of Tuesday morning. Image credit: weather.com. |

Wind chill is real!

Because wind chill is often described in terms of a “feeling”, it’s easy to think of it as something abstract. But wind chill has very real impacts on our bodies. It’s helpful to think of extremely low wind chill as a temporal signal, a sign that cold’s dangerous impacts will occur especially quickly.

When an adult is at rest, their average skin temperature is typically around 92°F. Most people experience discomfort, if not pain, by the time their skin cools to about 50°F. A strong wind on a cold day can help bring skin to that temperature very quickly. One study of exposure to 23°F air found that if the air was calm, facial skin cooled to about 81°F degrees in three minutes. However, with a 20-mph wind, parts of the face cooled all the way to the 50°F pain threshold in the same three-minute interval.

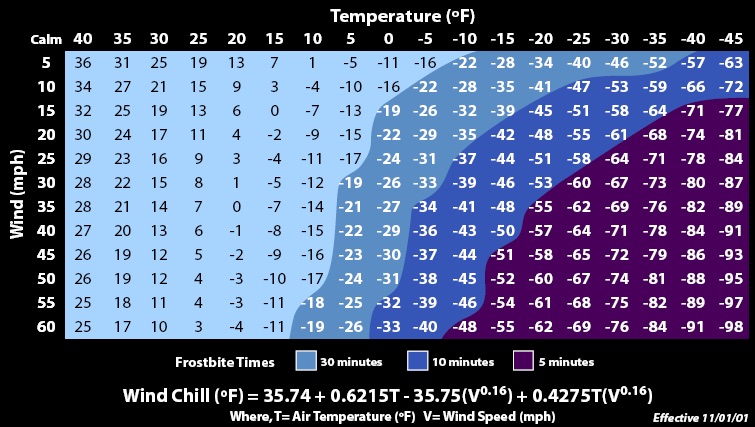

Frostbite occurs when body tissue freezes, such as your fingers, toes, ear lobes or the tip of your nose. With an air temperature of -20°F and a wind speed of 15 mph, frostbite can develop in 10 minutes or less. The stronger the wind when it’s cold out, the higher the risk for developing frostbite or hypothermia. Hypothermia occurs when your core body temperature, normally between 97°F and 99°F for adults, drops below 95°F.

(An interesting factoid: The long-held idea that normal body temperature is 98.6°F stemmed from research in the 1800s led by German scientist Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich. He rounded the results to the nearest degree Celsius, which happens to be 37°C, or 98.6°F. Subsequent work, including a 2018 study involving crowdsourcing, showed that the typical adult’s average body temperature is actually a bit lower, closer to 98°F, with normal ups and downs during the day.)

How wind chill got its start

The concept of wind chill was developed by two U.S. researchers, Paul Siple and Charles Passel, based on tests they carried out during the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition from 1939 to 1941. Their work examined the effect of wind in speeding up how quickly water froze in plastic cylinders. The resulting data on heat loss enabled Siple and Passel to estimate how quickly exposed skin might chill down at wind speeds of various strengths.

|

| Figure 2. Left: Charles Passel (left) with fellow participants in the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition. Right: More than 100 dogs hauled equipment across the barren landscape during the expedition. Image credit: Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, via Tennessee Aquarium Blog. |

The original formula developed by Siple and Passel and published in 1945 was later revamped to create the Wind Chill Equivalent Temperature, which the National Weather Service (NWS) put into regular use in 1973.

In April 2000, Environment Canada held a landmark online workshop on wind chill, with more than 400 participants from 35 countries. There was strong agreement that an international standard ought to be developed, so Environment Canada and the NWS embarked on research to revamp and improve the wind chill scale. One facet of this work involved directly measuring the effect of wind chill on humans. Volunteers at a Canadian military research center in Toronto were monitored at a variety of temperatures, both exercising and standing still, as a wind tunnel varied the amount of wind blowing on them. Because of limits on human experimentation, only the less-severe end of the scale was directly tested; wind speeds were kept to 27 mph or less.

One of the protocols involved a set of 90-minute walks at 50°F, 32°F, and 14°F, with each walk containing half-hour intervals of simulated wind blowing at 4.5, 12.5 and 18 mph (plus the walking speed of about 3 mph). For good measure, a fourth walk at 50°F involved a one-second splash of water in the face every 15 seconds!

Data from this research, together with computer modeling and tests involving a mannequin-like head, led to a revision of the wind chill scale, released in the U.S. and Canada and 2001.

|

| Figure 3. The current U.S. wind chill table, which was adopted in 2001. See the comment featured at bottom for a comparison of the pre- and post-2001 tables. Image credit: NWS, via Wikimedia Commons. |

The values in the 2001 scale, which is the one we use today, tended to run higher (less extreme) for a given temperature and wind speed than the previous version of the scale. One reason is the height at which the wind is measured. The old formula used standard temperature measurements, taken at a height of around 6 feet (2 meters), together with wind measurements that are typically taken at 33 feet (10 meters). However, friction near the ground tends to reduce the wind speed by about one-third at 6 feet (2 meters), which also happens to be close to the height of a typical adult’s face. The revised 2001 wind chill formula includes this one-third wind correction in order to simulate conditions that an adult would literally face head-on.

The revised formula also assumes you are walking at a typical pace of about 3 mph. The wind chill tables are constructed so that they take into account this effective wind on top of the measured wind.

With the new formula, Environment Canada began reporting wind chill as an index stripped of units, so that a calculated wind chill of, say, -30°C is communicated simply as -30. “The current index is expressed in temperature-like units because it is the format that was preferred by most Canadians,” says the agency. “However, since the wind chill index is not actually a real temperature but, rather, represents the feeling of cold on your skin, it is reported without the degree sign.”

Does sunshine make a difference?

Because sunlight reaching an object—including our skin—helps keep it warm, sunshine may slightly counteract the effects of wind chill on a bright, clear day as opposed to a cloudy one.

|

| Figure 4. Sunshine can make a difference in how cold you feel on a frigid midwinter day. Image credit: Bob Henson. |

“Wind chill equivalent temperature charts might someday include solar heating effects,” wrote researchers Randall Osczevski (Defence R&D, Canada) and Maurice Bluestein (University of Indiana) in a 2005 paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (open access). The paper details the work of Osczevski, Bluestein, and colleagues in developing the 2001 wind chill scale that we use today in the U.S. and Canada.

“Wind chill is an evolving concept,” noted Osczevski and Bluestein. “It seems unlikely that another half century will go by before wind chill is again upgraded.”

When the wind chill hits –100°F

There are only three times in U.S. records that the wind chill on the currently used scale appears to have hit -100°F. On January 16, 2004, New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Observatory, notorious for its harsh winter conditions, recorded a temperature of -41.8 degrees and a wind of 87.4 mph, leading to a wind chill of -102.6°F.

“It is unlikely that a lower wind chill has been measured at a long-term station in the U.S.,” says climatologist Brian Brettschneider, who covered U.S. and Canadian wind chill records in a blog post.

An automated weather station at Howard Pass, Alaska, recorded a temperature of -47.5°F with sustained winds of 53.7 mph at 10 p.m. on February 21, 2013. The resulting wind chill would have been minus -99.8°F. However, the winds were measured at a height of 10 feet, rather than the standard 33 feet, so the actual wind chill was more likely minus -105°F, according to Brettschneider.

Hourly temperature, wind, and wind chill at McGrath, Alaska, on Jan 27, 1989. the -100°F wind chill was observed at 6 a.m. @AlaskaWx @IARC_Alaska @weather_history 4/3 pic.twitter.com/JhrdHyeiN2

— Brian Brettschneider (@Climatologist49) January 27, 2019

Looking beyond such remote outposts, the lowest wind chill confirmed at a U.S. town or city (adjusting for the currently used wind chill scale) is -100°F at McGrath, Alaska, at 6 am AKST on January 27, 1989. The air temperature was -72°F at the time, and the wind speed was 7 mph. The extreme cold in McGrath was produced by an air mass that pushed from Siberia across North America over the next few days, leading to an intense cold wave in early February 1989 that extended all the way to Mexico City.

Interestingly, the wind chill of -100°F degrees in McGrath wouldn’t have even qualified for an NWS wind chill advisory, Brettschneider noted. This is because the wind was only 7 mph at the time, and NWS offices in Alaska do not issue wind chill advisories or warnings unless the wind is expected to be sustained at 15 mph or more for at least three hours.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.