| Above: Visible image from NASA’s MODIS satellite on July 27, 2019, reveals a wide expanse of fragmented Arctic sea ice beneath clear skies. Image credit: NASA, via Zack Labe (@zlabe). |

Over the next few days, meltwater will cascade across the Greenland Ice Sheet, and sea ice will dissolve into the Arctic Ocean in amounts that could be unprecedented for late July and early August. The same air mass that led to the sharpest, hottest heat wave ever recorded in northwestern Europe was channeled across Scandinavia over the weekend. Now it’s heading for even higher latitudes. While the North Pole won’t match the 108°F that Paris saw last Thursday, temperatures will be warm enough through a deep enough layer to push melting into overdrive for days, with knock-on effects that could last for weeks.

I am at the moment at Helsinki Kaisaniemi weather station, which shows temperature of 33.2°C. This the highest temperature ever recorded in the city of Helsinki, in any station. Records began in 1844. #HEATWAVE2019 pic.twitter.com/Eb6VHSriqq

— Mika Rantanen (@mikarantane) July 28, 2019

Already, sea ice extent in the Arctic is at record-low values for late July. The five-day average extent for the period ending Sunday, as calculated by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), was 6,576,000 million square kilometers. That’s 263,000 sq km below the record for the date (2011), and 338,000 sq km behind 2012—the year that ended up smashing all previous records for lowest minimum extent by September.

|

| Figure 1. Five-day average of sea ice extent for the period ending July 28, 2019, was at a record low for the date across the 40-year period of Arctic sea ice monitoring. Image credit: NSIDC. |

The problem isn’t just two-dimensional. Sea ice volume has also been at record-low levels for the time of year since late June, according to the PIOMAS volume-estimation model operated by the University of Washington. That’s especially worrisome because, for every unit area, less volume implies ice that’s thinner and easier to melt and disrupt.

In the Arctic, extremes often happen when an unusual event kicks off a sequence of positive feedbacks, processes that amplify the impact of the original event. The culprit in August 2012 was the Great Arctic Cyclone, a record-strong zone of surface low pressure for late summer that wandered across the central Arctic for more than a week, churning the waters and ice like a giant blender. Once dispersed into smaller fragments, huge swaths of ice were primed for additional melt through the rest of the warm season, which helped produce the record-low extent a few weeks later.

Even smaller cyclones can make a difference, according to Steven Cavallo (University of Oklahoma). On Figure 1 above, "each of those little bumps in July away from climatology have been associated with Arctic cyclones," Cavallo said.

A starkly different weather pattern is at hand this week, but it could help lead to a similarly dramatic loss of sea ice. “Instead of a strong vortex over the Arctic, the last few months have been dominated by high pressure and generally warm/sunny conditions,” said polar researcher Zack Labe (University of California, Irvine). “This has contributed to enhanced sea ice loss in several regions.”

Typically during boreal summer a relatively cold atmospheric column should favor low pressure in the #Arctic with warmest temperatures supporting subtropical high pressure. The remainder of July (1st plot) & all of July (2nd) anomalies shows the opposite. Seems '19 unusual to me! pic.twitter.com/dO7Tdwunh5

— Judah Cohen (@judah47) July 26, 2019

The upper-level high at the heart of Europe’s heat wave has now migrated north into Scandinavia, where it’s joining forces with another very strong upper high over the central Arctic. At the surface, strong high pressure is centered close to the North Pole. The pattern is keeping skies largely cloud-free and allowing still-ample summer sunlight to attack the ice in tandem with the unusual warmth flowing into the Arctic from lower latitudes. "This actually primes things for more sea ice loss later (on the order of weeks)," Cavallo said. "Temperatures will be warmer, and there will be less cloud cover to make sea ice more vulnerable if a cyclone were to develop down the road."

As the surface high weakens later this week and beyond, there will be the potential for one or more surface cyclones to develop along the edge of the remaining Arctic ice pack, where they could lead to further ice loss—but there’s no telling more than a few days out where or how strong those might be.

“Thus far, this year has been generally at or below 2012’s sea ice extent,” Labe noted. “However, there is room for caution. 2012’s Great Arctic Cyclone contributed to significant declines in sea ice extent in August. It will be difficult for 2019 to continue with a similar melt momentum without an extreme weather event, which are difficult (impossible?) to predict at this range.”

The Chukchi shocker

One area of particular concern is the Pacific side of the Arctic. Periodic infusions of mild air from the North Pacific have led to off-the-charts warmth in Alaska through much of this year. Warm oceanic and atmospheric currents from the south have attacked sea ice in the Chukchi Sea north of Alaska and Siberia, chewing on its fringes while shoving ice toward the Atlantic side of the Arctic.

July 2019 appears to be a near lock for the warmest month on record for Alaska. This estimate is based on station data through July 27 and the historical statistical relationship between those obs and the NCEI statewide temperature. @AlaskaWx @IARC_Alaska pic.twitter.com/5Dr6nezSVv

— Brian Brettschneider (@Climatologist49) July 28, 2019

Ice loss in the Chukchi has gotten especially dramatic over the past few days (see embedded tweet below). Areas of depleted ice cover now extend almost to 85°N on the Pacific side, less than 500 miles from the North Pole, and open water extends to 76°N.

Thread: Sea ice around Alaska is collapsing. Chukchi Sea ice extent is now 41% lower than the previous lowest (2017) for Jul 27 with open water to 76N. Big impacts from exposing so much water so early in the season. #akwx #Arctic #seaice @Climatologist49 @seaice_de @ajatnuvuk 1/2 pic.twitter.com/cH9MLdROlU

— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) July 28, 2019

Another region that bears watching over the next few days is the area north of Greenland, just east of to where the last remaining expanses of thick multiyear sea ice are clinging to the islands clustered at the north end of the Canadian Arctic. As noted in the Arctic Sea Ice Forum, very mild air, warming even more as it descends, will be flowing off the north coast of Greenland in the next several days. Satellite imagery over the last few days shows a crack developing where a large zone of Arctic sea ice is attached to the north coast of Greenland.

“The upcoming 2-3 weeks will be critical for predicting the minimum sea ice extent for 2019,” Labe said. “My takeaway is that this summer is consistent with expectations of a changing Arctic. The long-term trends are clear: Arctic sea ice is thinning, decreasing in area, and transitioning from older to younger ice.”

Big melt ahead in Greenland

The extraordinarily warm air mass is also likely to set off widespread surface melt atop the Greenland Ice Sheet. Especially concerning is the depth of the warm air—several miles—which will allow it to reach altitudes near the center of the ice sheet. On Friday, Norway’s highest-altitude weather station—Juvvasshøe, perched at 6214 feet—set a new all-time high of 18.9°C (66.0°F). Temperatures may nudge above freezing one or more times early this week all the way to Summit Camp, located at the apex of the Greenland Ice Sheet (elevation 10,551 feet). The camp has gotten as “warm” as 38°F in July, though the average high is in the low teens. The summit temperature was 31°F at midday Monday.

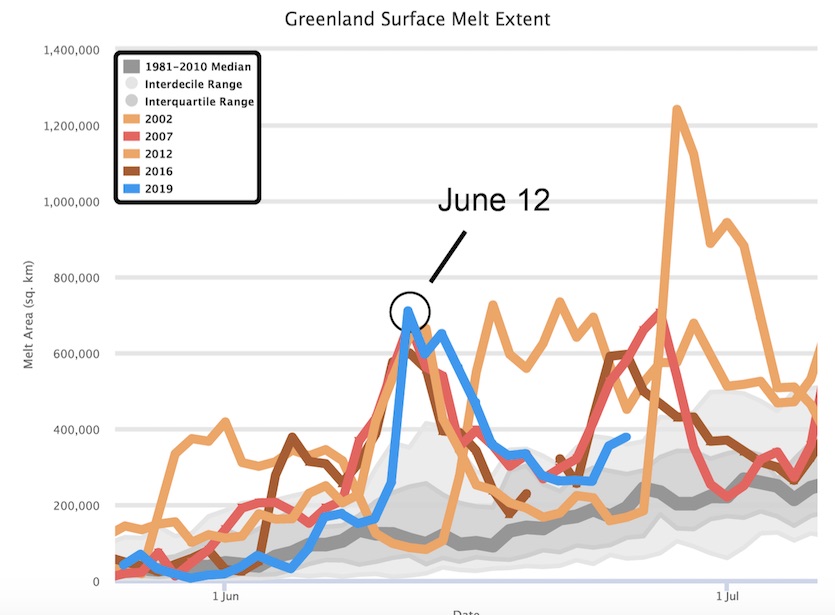

Scientists recognized months ago that 2019 could be a momentous year for Greenland ice. A melting spike in early May focused in southeast Greenland drew notice, and a more widespread round of surface melt in mid-June was the most expansive on record for so early in the year. The melt rate subsided later in June into early July, but then picked up again in recent days.

|

| Figure 2. Daily Greenland melt area from late May to early July for 2019 and for several other years with mid-June excursions in melting, showing that the event of 2019 was a record surface melt area for June 12. Data are from the MEaSUREs Greenland Surface Melt Daily 25km EASE-Grid 2.0 data set. Image credit: NSIDC and Thomas Mote, University of Georgia. |

Unlike the previous couple of winters, snowfall in 2018-19 was close to average for Greenland as a whole, but the snowfall was skewed more than usual toward the southeast part of the island, according to Theodore (Ted) Scambos (Earth Science and Observation Center, University of Colorado Boulder). Because southeast Greenland normally has a very thick snow cover to begin with, the extra snow there won’t affect runoff much, said Scambos. “Even in a low-to-normal year, you don’t get runoff [there]—you get percolation into the snow that refreezes.”

In contrast, the northern and western sides of Greenland, which are the ones more prone to have snowmelt flowing into the ocean, entered late spring and summer with less snowpack than usual. Here, according to Scambos, “if you don’t have much snow and you start turning up the temperature in summer, you melt through the snow that fell the previous winter and get to the snow below it.” That underlying surface is typically darker, the result of dust and soot that accumulated during the previous summer. In turn, the newly exposed darker surface—as seen in the animation below—absorbs more sunlight and hastens the melt process.

the dark anomaly spreads across Greenland ice and snow as melt intensifies @PolarPortal pic.twitter.com/M2YYNbZP6Q

— Prof. Jason Box (@climate_ice) July 27, 2019

The dramatic loss of sea ice in 2012 was accompanied by stunning melt atop Greenland, far more than in any year of monitoring since 1979. The net annual losses have continued since then, but at a somewhat reduced pace. As a 2018 study led by Jérémie Mouginot observed, “The acceleration in mass loss switched from positive in 2000–2010 to negative in 2010–2018 due to a series of cold summers, which illustrates the difficulty of extrapolating short records into longer-term trends.” Even so, they note, “enhanced glacier discharge has remained sufficiently high above equilibrium to maintain an annual mass loss every year since 1998.”

As best scientists can tell, “2017 and 2018 had very little mass loss,” said Scambos. There’s some uncertainty around these two years, because the GRACE satellite, which pinpointed changes in ice mass by measuring the gravitational tug of the ice, went out of service in 2016, and data from its replacement, GRACE-FO (for "follow-on") is just coming online. Other techniques involving altimetry and mass budgeting point to the likelihood of relatively modest ice loss in 2017 and 2018—by 21st-century standards, that is.

In the longer term, the prognosis for ice in Greenland and the Arctic remains bleak, especially if fossil fuel emissions continue unabated.

“We’re not going back,” Scambos said. “The evidence toward real impacts is continuing, and yet for the most part it’s been uneven amounts of response from policymakers toward addressing the problem.”