| Above: Fans sit in the covered section of the stands out of the heat during the second Formula One practice session at the Hockenheimring racetrack in Hockenheim, Germany, on Friday, July 26, 2019. It was the third straight day of temperatures exceeding 40°C (104°F) in parts of Germany, the nation’s longest such string on record. Image credit: AP Photo/Jens Meyer. |

In the wake of a massive heat wave across western and northern Europe, researchers at the Copernicus Climate Change Service have estimated that July 2019 was the planet’s warmest month on record, narrowly topping July 2016. Other groups that monitor monthly temperature, including NASA and NOAA, will be releasing their findings later in August.

The Copernicus group found that global temperature in July was about 0.04°C (0.07°F) warmer than July 2016. July is typically the warmest month of the year globally, running about 3-4 degrees Celsius warmer than January. This is because most of the planet’s land area – which warms faster than oceans – is located in the Northern Hemisphere, so the northern summer coincides with the warmest global average.

The Copernicus analyses extend back to 1979. Because of long-term global warming, this July’s record is effectively a record for at least the past century of global observation.

|

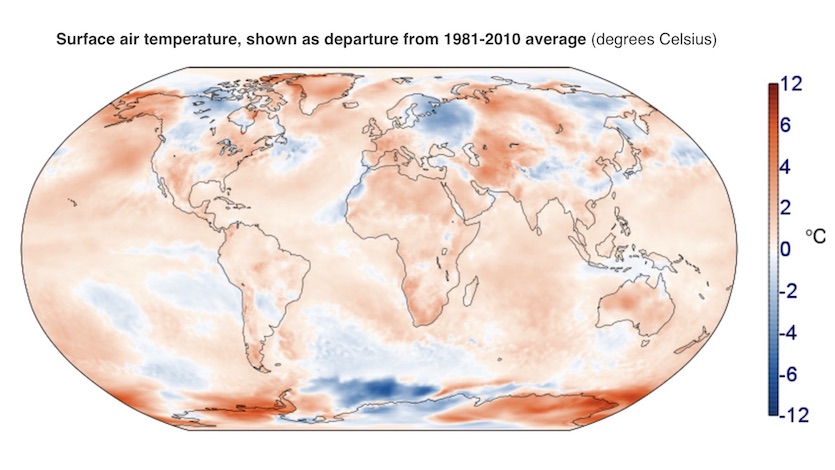

| Figure 1. July 2019 was the planet's warmest month on record, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service. Among the hottest spots relative to the 1981-2010 average were western Europe, central Asia, Alaska and most of Africa and Australia. Image credit: Copernicus/WMO. |

Most global heat records are set during or just after El Niño events, which bring warm undersea water to the surface across much of the tropical Pacific, thus warming the atmosphere above. This July’s record is especially striking because it occurred during a weak to marginal El Niño event. In contrast, the July 2016 record occurred at the tail end of one of the strongest El Niño events on record. While El Niño and La Niña tend to warm and cool the atmosphere for a year or two each, these events are happening on top of longer-term warming related to human-produced greenhouse gases, so the global warm spikes are getting warmer and the cool spikes less cool.

“We have always lived through hot summers. But this is not the summer of our youth. This is not your grandfather’s summer,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres, commenting last Thursday in New York on the likelihood of a new temperature record from Copernicus.

“Preventing irreversible climate disruption is the race of our lives, and for our lives. It is a race that we can and must win,” he added.

The Copernicus analyses are carried out by the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Different analyses of monthly global temperature (such as those from NASA, NOAA, and the Japan Meteorological Agency) can result in slightly different rankings, based on how groups account for data-sparse areas. The Copernicus analyses combine global temperature data from surface weather stations with background information from a forecast model that incorporates satellite and other data. The model analysis plays a larger role in regions with fewer weather stations.

|

| Figure 2. People cool off in Bayonne, southwestern France, Wednesday, July 24, 2019, where the temperature rose to 38°C (100.4°F). Europeans jumped into public fountains and the sea to keep cool as parts of the continent endured a record-breaking heat wave. Image credit: AP Photo/Bob Edme. |

Climate change made the heat wave in France and the Netherlands 10 to 100 times more likely

On Friday, the World Weather Attribution program released a fast-tracked analysis estimating that heat waves on par with the one striking France and the Netherlands in July are now 10 times—and perhaps 100 times—more likely as a result of human-produced climate change.

In France and the Netherlands, a comparable heat wave would be expected to occur once every 1000 years or less in a stationary climate. “Such temperatures would have had extremely little chance to occur without human influence on climate,” wrote the authors. The shorter (yet still record-smashing) periods of extreme heat observed in the United Kingdom and Germany would be expected to occur only every few decades to every few hundreds of years if the climate weren’t changing.

The report concluded:

“It is noteworthy that every heatwave analysed so far in Europe in recent years (2003, 2010, 2015, 2017, 2018, June 2019, this study) was found to be made much more likely and more intense due to human-induced climate change. How much more depends very strongly on the event definition: location, season, intensity and duration. The July 2019 heatwave was so extreme over continental Western Europe that the observed magnitudes would have been extremely unlikely without climate change.”

Hot spots in a scorching July

Dozens of European cities set new all-time high temperature records in July, including Paris, France (108.7 degrees); Amsterdam, Netherlands (97.3 degrees); and Helsinki, Finland (91.8 degrees). See our roundups of heat records for July 23-24 and July 25. On July 25 alone, five nations saw their hottest temperatures ever recorded:

Belgium: 41.8°C (107.2°F) at Begijnendijk

Germany: 42.6°C (108.7°F) at Lingen

Luxembourg: 40.8°C (105.4°F) at Steinsel

Netherlands: 40.7°C (105.3°F) at Gilze Rijen

United Kingdom: 38.7°C (101.7°F) at Cambridge

Another part of the world with extreme warmth in July was Alaska. At least 13 Alaska locations chalked up their hottest month on record, and the state very likely hit such a mark as well, according to climatologist Brett Brettschneider. The Anchorage airport hit 90 degrees Fahrenheit on July 4, breaking its all-time record by 5 degrees, and the city had its warmest month on record by far.

The Alaskan heat has occurred in tandem with record-low sea ice extent in the Chukchi Sea to the north, as well as across the entire Arctic.

“A river usually teeming with life felt like a tomb.” @KYUKNews reports salmon die-offs in #Alaska this summer are likely tied to abnormal heat. They’re “really tough,” says @uafairbanks prof. “So if salmon are dying, it points to something serious.” https://t.co/MM4MbzGCB6

— David Dodman (@daviddodman) August 5, 2019

July was considerably cooler than average over parts of eastern Europe and far western Russia. Much of eastern Canada and parts of the south-central U.S. were also cooler than average for July, with a dramatic cool spell in late July setting daily record lows across the South. However, several cities in New England—including Boston—had their hottest month on record.

All-time high temperature records have been broken this year in 13 of the world’s nations and territories, and tied in another. In contrast, no all-time national cold records have been broken thus far in 2019. The largest number of all-time national/territorial heat records set or tied in a single year was the 22 heat records that occurred in 2016, according to international records researcher Maximiliano Herrera. The runners-up are 2019 and 2017, each with 14 heat records.

Jeff Masters will have a full report on July’s global temperatures following the release of the NOAA report later this month.