| Above: Volunteers from across the state helped rescue residents and their pets from their flooded homes during Hurricane Florence on Friday, September 14, 2018, in New Bern, North Carolina. Flooding initially related to Florence's storm surge forced of people to call for emergency rescues in the area around New Bern, which sits at the confluence of the Nuese and Trent rivers. Image credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images. |

Relentless rainbands sweeping around Tropical Storm Florence continue to drench parts of North and South Carolina already waterlogged after days of torrential downpours. Florence’s center—located about 40 miles west of Myrtle Beach, SC, at 11 am EDT Saturday, with top sustained winds down to 45 mph—was drifting west at just 2 mph. This painfully slow progress, together with Florence’s vast field of moisture, is a recipe for catastrophic rains through the weekend and potentially devastating floods into the coming week. Several rivers across the region are already predicted to set all-time record crests by Tuesday or Wednesday, including the Lumber and Cape Fear rivers, which caused massive flooding just two years ago during Hurricane Matthew.

|

| Figure 1. Infrared-wavelength satellite image of Tropical Storm Florence as of 1427Z (10:27 am EDT) Saturday, September 15, 2018. Image credit: NASA/MSFC Earth Science Branch. |

The heaviest rainbands in Florence on Saturday morning continued to plague the southernmost slice of North Carolina, mainly north and east of Wilmington. Multiple flash flood emergencies have been issued by the National Weather Service across this region, and many water rescues have been reported.

A trained CoCoRaHS observer 1.4 miles north of Swansboro reported 14.25" in the 24 hours through 8:30 am Friday and 16.33" through 8:30 am today. Together with 0.01” on Thursday, that yields a storm total so far of 30.59”. CoCoRaHS reports are manually collected from rain gauges, so when properly located, they are typically more reliable than automated rain gauge reports. We know that the Friday and Saturday totals are underestimates, because the 10” gauge was reported as “full” despite having been checked more than once during the day. Assuming the Swansboro readings are confirmed, they will smash the NC state record for the largest amount of rain dumped by any tropical cyclone: 24.06", during Hurricane Floyd in 1999. It was still raining near Swansboro on Saturday morning.

The extreme rainfall band is being driven by the long fetch of moisture flux convergence over the warm SSTs of the #GulfStream. This helps to reinforce the band as it rains out over over land in coastal NC.

— Philippe Papin (@pppapin) September 15, 2018

Essentially the same setup we had with rainbands in #Harvey. #ncwx pic.twitter.com/tnqKOhzRAJ

Incredibly, the high-resolution HRRR model predicts that 20” or more of additional rain will fall in the period from 8 am Saturday through 5 pm Sunday across a swath stretching north and west from Wilmington (see Figure 2 below). Wilmington received 0.02” on Tuesday, 0.60” on Wednesday, 1.50” on Thursday, and 9.58” on Friday, plus more than 3” through late morning Saturday, so it’s quite possible the city will top 30” for its storm total if the HRRR is correct. Wilmington also has a good chance on Saturday of breaking its all-time daily precipitation record of 13.38”, set on September 15, 1999, during Hurricane Floyd.

|

| Figure 2. Rainfall totals predicted by the 12Z Saturday run of the HRRR model from Saturday morning through Sunday afternoon, September 15-16, 2018. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

It may be hard to believe...but there's MUCH more rain to come.

Parts of the Carolinas will see more than 15 inches of additional rain in the next couple of days. #Florence pic.twitter.com/vEgFEuTlZF

— NWS (@NWS) September 15, 2018

It may be hard to believe...but there's MUCH more rain to come.

Parts of the Carolinas will see more than 15 inches of additional rain in the next couple of days. #Florence pic.twitter.com/vEgFEuTlZF

Florence's flood threat to spread westward and northward

Florence will be inching its way across South Carolina from Saturday into Sunday, eventually weakening to a tropical depression. As Florence’s circulation shifts inland, the heaviest rains will move into western North Carolina, where upslope flow against the Appalachians could wring out 5” – 10” or more, bringing yet more flash flood risk as well as the threat of mudslides and rockslides. By late Sunday, Florence should begin to accelerate on an arcing path around the blocking ridge of high pressure that kept Florence from moving out to sea. Rains from the remnants of Florence won’t be as heavy across West Virginia and western Pennsylvania as they were in the Carolinas, but the saturated soils in this region may still lead to a significant flood threat, and residents of the Washington-Baltimore area should keep an eye on any eastward extension of Florence’s rains. Even southern New England could get widespread 1” – 3” totals on Tuesday before ex-Florence finally heads back over the Atlantic.

More than 750,000 customers in North Carolina were without power on Saturday morning, and at least five storm-related deaths had been confirmed. For more on impacts from Florence, see the frequently updated weather.com feature.

|

James Belanger:

The Flooding Deluge and Aftermath

Below is a guest contribution from James Belanger, a senior meteorological scientist for The Weather Company, an IBM Business. James is responsible for providing scientific expertise in the design and implementation of TWC's artificial intelligence algorithms for consumer and business weather products.

One of the more difficult impacts from hurricanes to convey to the public is the risk of flooding. Flooding can be manifest in different ways depending upon the evolution of the hurricane as it moves inland. As the outer rainbands impact an area, those rainbands can cause flash flooding due to high rates of falling precipitation, leading to the rapid accumulation of water over a short period of time. Along the coast, storm surge from a large, formidable hurricane like Florence whose center moves onto land can cause extensive coastal flooding from the rapid rise of ocean water onto the coast, leading to water level heights several feet above ground.

Then there is the impact of river flooding. As streams and rivers overflow their banks from rainfall that has collected over an areal basin, it is funnelled via rivers and streams back toward the ocean. This aspect of river flooding can cause areas within a floodplain—the low-lying region adjacent to a river—to experience flooding conditions that may persist for several days, preventing people from crossing bridges that might be critical for transportation or from returning to their homes due to waterlogged streets and homes.

The forecast flooding from Hurricane Florence along the coast stretching from Charleston, SC, to Morehead City, NC, and then inland through the Carolinas has been mind-boggling. This flooding will be due to the combination of several feet of storm surge along the coast and historic rainfall amounts that are expected due to the hurricane’s slow movement inland. Due to the unusual trajectory that Florence will take as it moves inland into the Carolinas, coastal flooding from storm surge and then later from river flooding will be further exacerbated by persistent onshore flow for days to come, which will act to inhibit river flood water from receding back into the ocean.

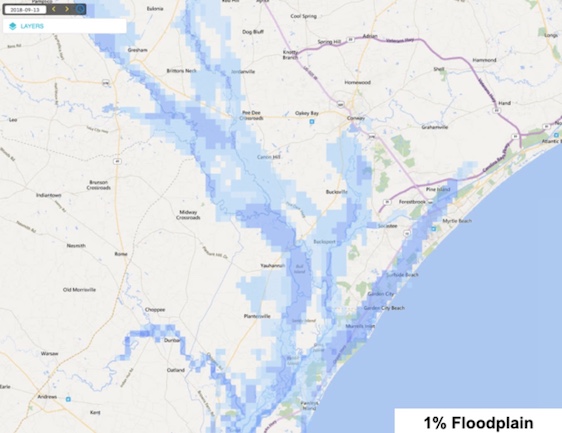

One of the ways we can characterize the magnitude of flooding specifically due to river impacts is by describing how rare a flood event may be in a given year. One of the most common thresholds used is flooding that has a 1% chance to occur in a given year. Homeowners who carry mortgages whose homes are located in areas with a 1% chance of flooding, also known as the 100-year floodplain, are familiar with this threshold as they are required to carry flood insurance, typically from the National Flood Insurance Program.

|

| Figure 3. Snapshot of the river flooding and inundation for a flood event that has a 1% chance of occuring in a given year across portions of northeast South Carolina. Note: The effect of storm surge and coastal flooding is not included in this image. |

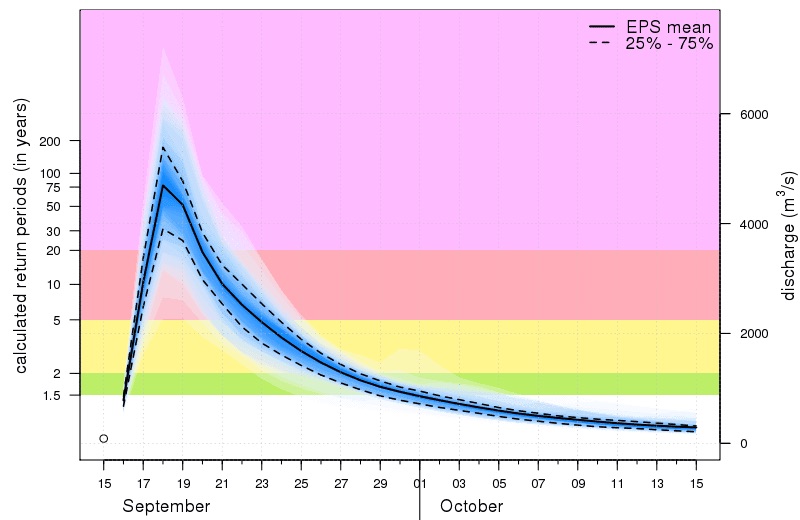

Forecast tools exist today that can be used to assess the likelihood that river flood impacts may occur and for how long. One of those forecast systems that is being used for river flooding from Hurricane Florence is the Global Floods Awareness System (GloFAS) which is a joint system developed by the European Commision and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). This modeling system takes Hurricane Florence’s potential direction and speed of movement, along with where and how much rainfall will accumulate, and couples it to a hydrological model—the river analogue to a weather model. The end product is a set of river forecast scenarios that can be used to describe how much water may pass through a location on the river, which is a measure of flood potential.

|

| Figure 4. GloFAS streamflow forecasts for Georgetown, South Carolina, based on ensemble output from the ECWMF global model run initialized at 0Z Saturday, September 15, 2018 (8 pm EDT Friday). Image credit: GloFAS, courtesy James Belanger. |

How bad will the flooding be, and when will it end?

Forecasts from GloFAS based on Friday-night (00Z Saturday) runs of the ECMWF model suggest there is a significant likelihood (40% chance) of seeing river flooding consistent with the flooding inundation of a 1% flood in the vicinity of Georgetown to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. This means the risk of seeing significant flooding and inundation of this magnitude is 40 times greater than normal. The river flooding would become most significant on Sunday, with the worst extent and impacts on Tuesday. It may not be until next weekend before the river water finally recedes from the floodplain along the northern South Carolina coast. The delay in flood waters receding will be compounded by winds forecast to blow onshore as Florence moves inland. These projections suggest an increasing likelihood of prolonged coastal flooding through next week, making it difficult if not impossible for residents to return their homes in this area until the water finally recedes. This area is also home to the second largest seaport in South Carolina, suggesting a prolonged period of disrupted cargo transportation and port operations.

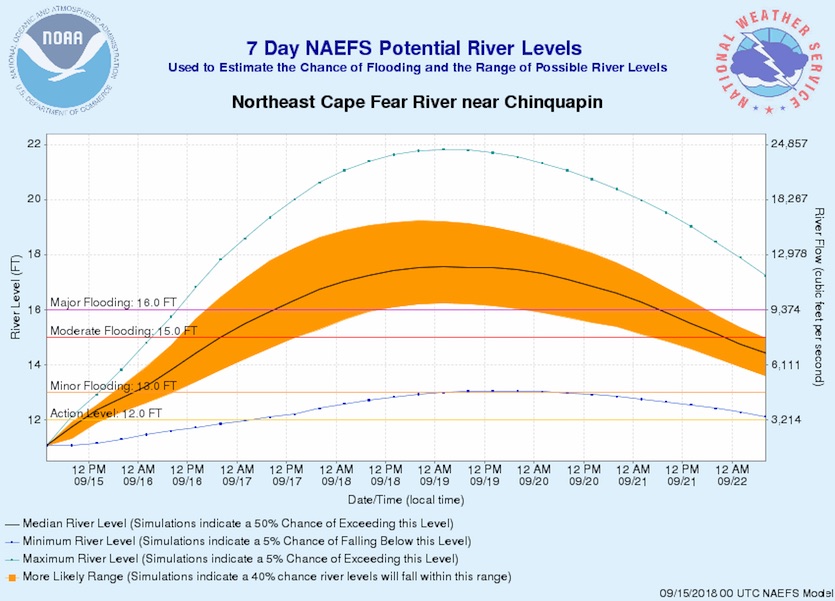

Like GloFAS, the National Weather Service Eastern Region produces probabilistic river flow forecasts that are based on weather model forecasts from the GFS-based Global Ensemble Forecast System (GEFS) and from the U.S.-Canadian North American Ensemble Forecast System (NAEFS) coupled to a hydrological river model. These projections are used by forecasters to help convey the uncertainty that exists in flooding potential over the next week. Although these forecasts extend through next week, where in some cases major flooding along the coast will continue to persist, they similarly highlight the long duration of flooding that is expected across North Carolina from Florence, especially as you get closer to the coast.

|

| Figure 5. A probabilistic river stage forecast based on rainfall generated in the 00Z Saturday run of the NAEFS model ensemble system shows an 72% chance of major flooding on the Northeast Cape Fear River near Chinquapin. The highest stage on record for this site is 23.51 feet on September 19, 1999, following Hurricane Floyd. A separate NWS outlook, based on shorter-term, higher-resolution model output, suggests that the flooding may end up even higher than indicated by the ensemble, perhaps breaking the record from Floyd. |

Dr. Jeff Masters will have an update later today on Typhoon Mangkhut.