| Above: Tree trunks and debris washed away by flash floods are seen lodged in a damaged house in Sentani near the provincial capital of Jayapura, in Indonesia's eastern Papua province, on March 17, 2019. (Netty Dharma Somba / AFP / Getty Images). |

The death toll has risen to 104 in Indonesia's easternmost province of Papua on the island of New Guinea, after torrential rains on Saturday night and Sunday morning triggered destructive flooding and mudslides. Another 159 people have been injured, and 79 are missing. Nearly 10,000 people are in shelters. Destroyed roads and bridges have hampered relief efforts, as have intermittent heavy rains. The flood is the 2nd deadliest weather disaster on Earth so far in 2019, behind the horrific toll Tropical Cyclone Idai has wrought in Mozambique and neighboring nations.

|

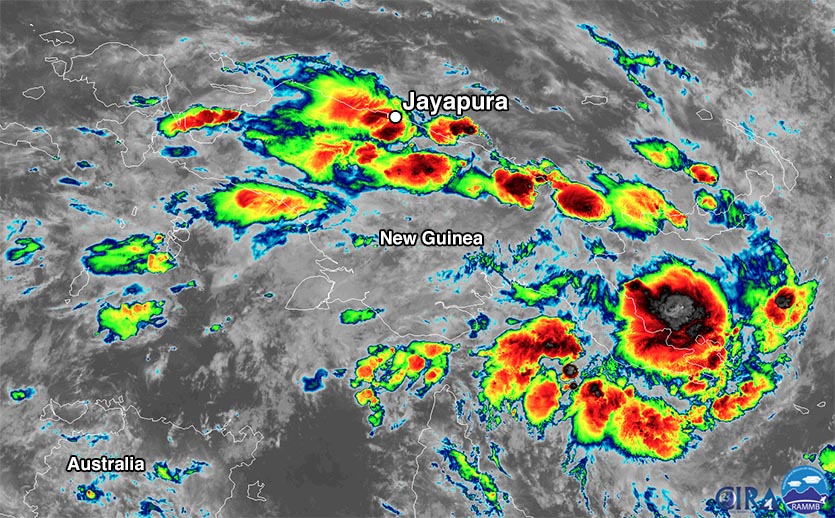

| Figure 1. Infrared satellite image of the island of New Guinea taken at 16Z March 16 (1 am local time Sunday, March 17). Heavy thunderstorms were bringing torrential rains to Jayapura, the capital of Indonesia’s Papua province. Image credit: NOAA/RAMMB. |

A partially human-caused disaster

Seasonal rains cause frequent landslides and floods that kill dozens each year in Indonesia, a nation of some 17,000 islands where millions of people live in flood-prone mountainous areas or river deltas. Sutopo Purwo Nugroho, a spokesman of the national disaster agency, told Reuters that his agency had warned local governments in 2018 of flash flood risks due to deforestation in the Cyclops Mountains where the disaster occurred. “Forest destruction in the Cyclops Mountains have increased for use as firewood and to turn the land into plantations,” he said.

This week’s disaster was the second major deadly flood of 2019 in Indonesia where deforestation was partially to blame. During the last week of January, heavy rains in excess of 300 mm (11.81”) in 24 hours hit South Sulawesi, triggering floods that killed 80 people. Many of the deaths occurred due to the overflow of the Bili-Bili Dam. Deforestation on the mountainside of the watershed surrounding the dam’s reservoir had allowed a large amount of sediment to flow into the reservoir since the dam was built in 1997. The resulting decreased storage capacity of the reservoir allowed flood waters to overtop the dam and force the opening of its emergency flood gates, contributing to the deadly disaster. Speaking to the Thomson Reuters Foundation shortly afterwards, South Sulawesi Governor Nurdin Abdullah rejected the media's portrayal of the disaster as “natural”. “That dam was intended to last 100 years,” he said.

In a Wednesday editorial, the Jakarta Post commented: “We have played a part in the disasters by supporting unsustainable development, evident in the rampant deforestation, which only takes quick dollars into consideration. Unless we change now, more floods and landslides will threaten our children tomorrow.”

Flooding in Indonesia and northern Australia: Not the usual El Niño fare

Based purely on El Niño, we might have expected drier-than-average conditions in northeast Australia and Indonesia over the last few months. Yet while east-central Australia has been quite dry since October, Queensland has been hammered with major flooding near Townsville in February, followed by this week's landfall of Tropical Cyclone Trevor. Several sites in northern Queensland received an astounding one to two meters (39 to 79 inches) of rain from late January into mid-February. What's more, the Indian Ocean Dipole was in a weakly positive mode in late 2018 (it has since gone neutral). A positive IOD tends to reduce the odds of rain over much of Australia, and the combination of El Niño and a positive IOD is especially likely to produce drought over Indonesia, as highlighted in an open-access 2017 study led by Harisa Bilhaqqi Qalbi (Bogor Agricultural University). Of course, short-term rainfall extremes can trigger flash flood disasters in Indonesia and elsewhere regardless of seasonal trends.