| Above: Motorists navigate an ice and snow-covered road on November 27, 2019, in Mason City, Iowa. A storm pushing across the Midwest and Northeast hampered holiday travel during the long Thanksgiving weekend. Image credit: Scott Olson/Getty Images. |

November’s ups and downs across the contiguous U.S. added up to a month that was slightly cooler and dryer than average, according to summary maps issued Monday by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). The month came in as the 48th coolest and 32nd driest out of 125 years of recordkeeping.

Chilly air masses poured from Canada across the eastern two-thirds of the country in early November, keeping most states east of the Rockies well below average for the month. No monthly statewide records were set, but Vermont had its ninth coldest November and Mississippi its tenth coldest. West of the Rockies, mildness dominated. California had its tenth warmest November on record.

|

| Figure 1. Statewide rankings for average temperature for November 2019, as compared to each November since records began in 1895. Darker shades of red indicate higher rankings for heat, with 1 denoting the coldest month on record and 125 the warmest. Image credit: NOAA/NCEI. |

The cold skew of November comes through even more sharply in local records, which reflect the intensity of the early-month cold blasts. NCEI’s U.S. Records site shows a preliminary total of 2821 daily record lows broken or tied in November, compared to just 737 daily record highs. Likewise, there were 2451 record low maxima but only 654 record high minima.

The frequent infusion of dry, chilly air masses also tamped down on rainfall. Most U.S. states were either near or below average on precipitation. Yet snowfall was surprisingly widespread across parts of the Great Plains, Midwest, and Northeast, a result of the unusually cool temperatures as well as several bouts of early-season snow that gave some spots their fastest start to the snow season on record, including Wichita, KS (2.7” by November 12) and Madison, WI (15.7” by November 23) . Meanwhile, an intense, slow-moving upper-level storm over Thanksgiving week led to heavy rains and mountain snows over the Southwest, helping push Arizona to its third wettest November and New Mexico its fifth wettest.

It was a far different picture in the Pacific Northwest, where Idaho and Washington had their fifth driest November on record and Oregon its seventh driest. As noted by weather.com, this was only the third November on record to give Salem, OR, less than an inch of rain. In Washington's Mount Rainier National Park, Paradise Ranger Station—infamous for its massive snowpack—picked up only 8 inches of snow in November, a dusting compared to its November average of 110.9 inches.

|

| Figure 2. Statewide rankings for precipitation for November 2019, as compared to each November since records began in 1895. Darker shades of green indicate higher rankings for moisture, with 1 denoting the driest month on record and 125 the wettest. Image credit: NOAA/NCEI. |

Autumn 2019 and year to date: The wet footprint is still there

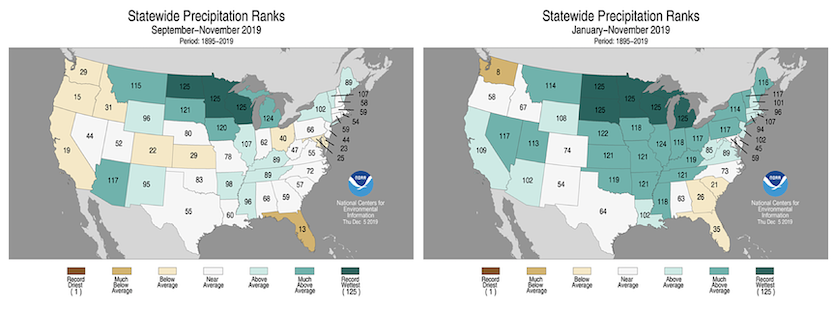

There are signs that the extremely wet conditions of the past year-plus are starting to abate for the contiguous U.S. as a whole, but excessive moisture is still a huge concern from the Northern Plains to the Upper Midwest. Autumn 2019 (September-November) was the wettest on record for Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin, and among the five wettest in Michigan and South Dakota.

NOAA projects that winter 2019-20 may continue wetter than average over the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes. Together with soils that are already saturated, this spells potential trouble with Midwestern spring flooding in 2020. As of Monday, the Missouri River was at record-high levels for the date at Kansas City, Missouri, and large stretches of the Mississippi River are at near-record levels for the date.

|

| Figure 3. Statewide rankings for precipitation for autumn 2019 (left) and the year to date (right). Image credit: NOAA/NCEI. |

For 2019 to date (January through November), this has been the wettest year on record for the contiguous U.S. as well as for the states of Michigan, Minnesota, North and South Dakota and Wisconsin (see Figure 3 above). Almost every state has seen above-average precipitation for 2019 thus far, though in many states that’s largely due to soggy conditions in the first few months of the year.

In order for 2019 to become the wettest year on record nationwide—topping the 34.96” from 1973—December will need to produce an average of at least 2.83”, which is on the high side for that month but not exceptionally so.

Going back a bit further, the last 12 months have been the wettest December-to-November period in U.S. records, with the national average of 35.39” breaking the old record of 35.08” set in 1982–83. It’s far from the wettest of any 12 months, though. Below is that list.

37.86" July 2018–June 2019

37.73” August 2018–July 2019

37.68” June 2018–May 2019

37.55” September 2018–August 2019

36.45” October 2018–September 2019

36.21” November 2018–October 2019

36.20” May 2018–Apr. 2019

35.95” May 2015–Apr. 2016

35.78” Apr. 2015–Mar. 2016

35.73” Mar. 2018–Feb. 2019

Amazingly, all ten of these 12-month spans have occurred in the last six years—and the seven wettest have all occurred since 2018. Even given the fact that a very wet span of a few months will be factored into such listings more than once, this is still remarkable testimony to the power of our warming climate to make extreme rain events even more extreme.

|

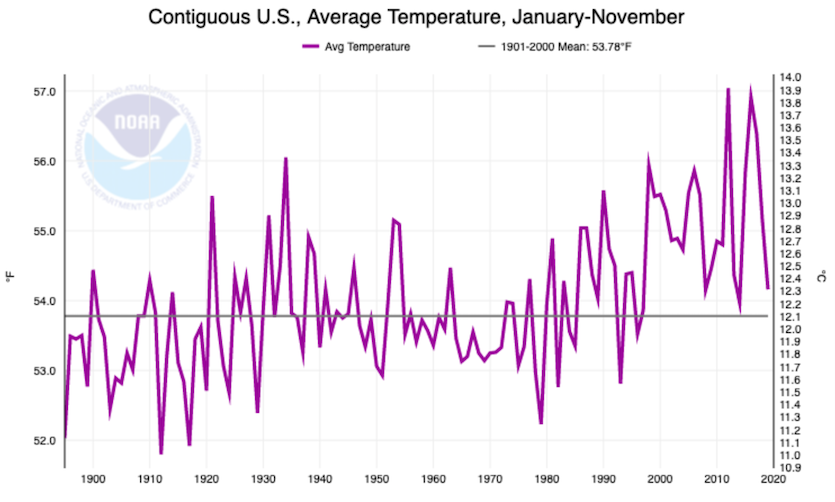

| Figure 4. Year-to-date (January-November) temperatures averaged across the contiguous U.S. from 1895 to 2019. Image credit: NOAA/NCEI. |

One of the world’s hottest years on record—but not so for the contiguous U.S.

A startling global-vs-U.S. contrast in temperatures is another key feature of 2019 as we near its end. This year through November is only the 45th warmest year to date for the contiguous U.S., and the coolest since 2014. That year was the last time daily record lows outnumbered daily record highs, and it may happen again this year, according to meteorologist Guy Walton. However, 2019 has also the warmest year to date in Alaska—and it will likely be the second or third warmest year globally, as noted in a sobering report last week from the World Meteorological Organization. Keep in mind that the contiguous U.S. represents only 5.4% of the planet’s land area, and only about 1.6% of Earth’s total surface area (land plus ocean).

Globally, “the five-year (2015-2019) and ten-year (2010-2019) averages are, respectively, almost certain to be the warmest five-year period and decade on record,” reported the WMO in a news release. “Since the 1980s, each successive decade has been warmer than the last.”

The WMO report occurred at the start of the UN's two-week-long 25th Conference of Parties (COP 25) meeting in Madrid, whose goals include preparing for the next phase of the Paris Agreement to limit greenhouse emissions. We’ll have more on the Madrid meeting in an upcoming post.

The fact that 2019 concludes a decade of exceptional global heat and massive #climatechange impacts, as reported by @WMO today, is powerful motivation for delegates at #COP25 to finish outstanding work and raise #ClimateAmbition > https://t.co/waP62r9Kin #TimeForAction pic.twitter.com/wn5JyYNAzx

— Patricia Espinosa C. (@PEspinosaC) December 3, 2019