| Above: GOES_16 infrared image of Hurricane Michael at 5:30 pm EDT October 9, 2018. Image credit: NOAA/RAMMB. |

Dangerous Hurricane Michael is now a Category 3 storm with 120 mph winds as it churns northward at 12 mph towards an expected landfall in the Florida Panhandle on Wednesday afternoon. A storm surge of over two feet is already affecting the Panhandle, and weather conditions will deteriorate tonight. If you live in an evacuation zone for storm surge and have been told to leave, get to your safe shelter inland tonight! You may not be able to evacuate safely on Wednesday.

Two hurricane hunter aircraft were in Michael late Tuesday afternoon, and reported that Michael had still not closed off an eyewall around its 20-mile diameter eye. The eye was also not very warm—about 5 - 6°C warmer than the air just outside the eye, which is low for a major hurricane. These factors suggested that Michael was still having trouble with the moderate wind shear of 10 - 15 knots affecting it, and had not mixed out dry air from its core. Until Michael does manage to close off a complete eyewall, intensification will likely be at the rather moderate pace we’ve seen over the past day.

|

Figure 1. Predicted surface winds (colors) and sea level pressure (black lines) for 2 pm EDT Wednesday, October 10, 2018, from the 12Z Tuesday run of the HWRF model. The model predicted that Michael would be making landfall as a high-end Category 3 hurricane with 125 mph winds near Panama City, FL. Image credit: Levi Cowan, tropicaltidbits.com. |

Intensity forecast: Cat 3 or 4 at landfall

If Michael does manage to form a complete eyewall, a period of more rapid deepening may ensue, where the central pressure drops to the 930 – 935 mb range by landfall. A pressure of this magnitude would be capable of driving peak sustained winds of 145 - 150 mph. However, there is typically a lag of about 4 - 6 hours between when the pressure falls and when the winds catch up to the new lower pressure, and Michael may make landfall before its winds can respond to any explosive deepening phase.

The official NHC intensity forecast at 5 pm EDT Tuesday called for Michael to be a high-end Category 3 hurricane with 125 mph winds at 2 pm Wednesday, a few hours before the time of landfall. Given the uncertainties in intensity forecasting, we should not be surprised if Michael was anywhere from a Category 2 storm with 110 mph winds to a Category 4 storm with 140 mph winds at landfall. The 12Z Tuesday run of our top intensity model from 2017, the HWRF model, predicted landfall early Wednesday afternoon as a Category 3 hurricane with 115 – 120 mph winds. The 12Z Tuesday run of the HMON model predicted landfall as a Category 4 hurricane with 130 mph winds. Our other two top intensity models, the DSHIPS and LGEM, predicted that Michael would make landfall as a Category 3 hurricane with 125 mph winds. Landfalling Category 4 hurricanes are rare in the mainland U.S., with just 24 such landfalls since 1851—an average of one every seven years. (Category 5 landfalls are rarer still, with just three on record).

Our two most reliable rapid intensity forecasting models, the SHIPS and DTOPS, predicted with their 18Z Tuesday forecasts that Michael had a 24% chance of becoming a mid-strength Category 4 hurricane with 140 mph winds before landfall. SHIPS is the model NHC uses operationally to forecast rapid intensification, and DTOPS is an experimental model that NHC started evaluating last year.

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are near 29°C (84°F) across the eastern Gulf, which is 1 - 2°C (2 - 4°F) above average for this time of year. Even though it is early October, no cold fronts have yet chilled the waters near the central Gulf Coast, so very warm surface waters are in place to support Michael right up to landfall.

9 major #hurricanes have made landfall in the Florida Panhandle on record (since 1851). Here's the landfall stats on each of these storms. #HurricaneMichael #Michael pic.twitter.com/ocGsHS0q8i

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) October 9, 2018

Michael’s potentially devastating landfall in the Florida Panhandle may also carve a deep groove in hurricane history. In records going back to 1851, only nine hurricanes have struck the Panhandle with Category 3 or stronger winds. The strongest were the 1882 Pensacola hurricane and 1975’s Hurricane Eloise, both of which came ashore with winds of 125 mph, so Michael thus has a chance of becoming the strongest landfalling hurricane ever recorded for the Florida Panhandle.

#Alabama, #Georgia, #SouthCarolina, and #NorthCarolina: just because #Michael is going to make landfall in #Florida doesn't mean it ends there. Tropical storm conditions likely across long swath as the storm exits, and even chance of hurricane-force winds in coastal SC and NC. pic.twitter.com/PKKQu26hD1

— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) October 9, 2018

High confidence in Michael’s track

Michael is being steered by two large, powerful features—a deep upper low in the western U.S. and a summerlike ridge off the East Coast. Because these features are so big and slow-moving, the flow between them will guide Michael on a pretty predictable path. Computer models have converged strongly on a track that sends Michael northward until early Wednesday. The hurricane will take a northeastward turn starting around or just before landfall.

There is some modest uncertainty in the landfall location, based mainly on when models believe the turn will begin. Even so, nearly all of the Tuesday morning (12Z) suite of model guidance agrees that Michael will make landfall in the Florida Panhandle west of Apalachicola. The hurricane warning covers a larger area than this, in part because there is always the chance of a last-minute shift toward the west or east, but also because Michael’s impacts will be widespread regardless of exactly where its center comes ashore. The strongest winds and largest storm surge will tend to occur on Michael’s east side; the heaviest rains will move inland on a swath within 50 – 100 miles of Michael’s center.

As the western low moves into the Great Plains, it will shunt Michael on an accelerating northeastward path across Georgia and the Carolinas from late Wednesday into Thursday. Because Michael will be moving at 20 – 30 mph, it will cover large amounts of territory before its winds have a chance to weaken much. Thus, a large swath near and east of Michael’s center will be at risk of winds strong enough to bring down trees and power lines—a deadly threat that could knock out power to hundreds of thousands of people as far northeast as parts of the Carolinas.

As it sweeps through the Southeast, Michael will be dropping 4” – 8” of rain within roughly 100 miles of its center, leading to a risk of localized flash floods. Fortunately, Michael’s rapid forward motion will prevent the kind of massive multi-day rainfall that occurred during slow-moving Hurricane Florence. Rivers have receded dramatically over the Carolinas since Florence, so widespread river flooding is not expected, but the large amounts of soil moisture still in place will exacerbate the flash-flood threat.

Michael is expected to move back over the Atlantic early Friday, exiting the U.S. from the Virginia or North Carolina coast. These areas could experience a parting shot of strong wind from Michael, which is expected to regain some strength as it accelerates out to sea. The European model track is farther south than its counterparts at this point, showing Michael paralleling the North Carolina coast; such a track would allow for Michael to maintain stronger winds than an inland track.

|

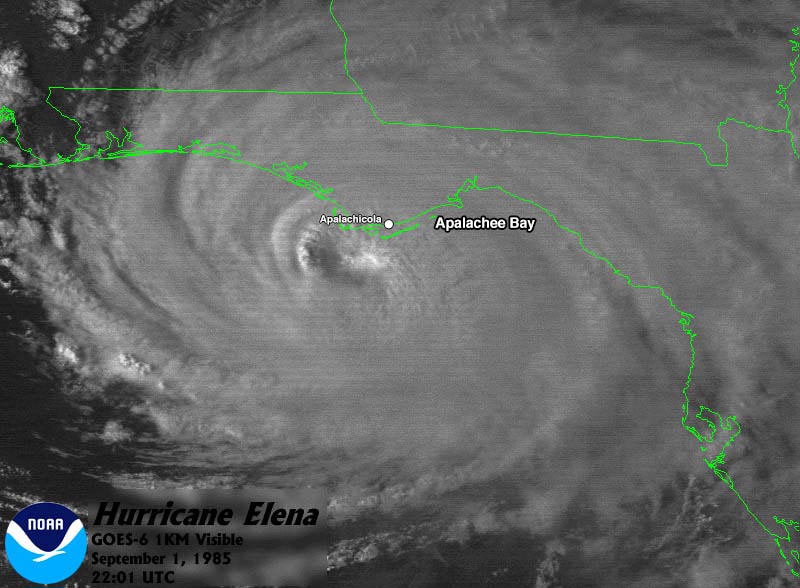

| Figure 2. Category 3 Hurricane Elena passing just south of Apalachicola, FL, on September 1, 1985. Elena brought the highest storm surge on record to Apalachicola: 10 feet. Image credit: NOAA. |

High storm surge risk on east-facing locations on Apalachee Bay

One of the most at-risk locations for a high storm surge is Apalachicola, FL. Storm surge expert Dr. Hal Needham’s U-SURGE project has a web page dedicated to the storm surge history there. In an email, Dr. Needham explained that the page allows us to compare Michael's surge with high water marks from 40 other hurricanes and tropical storms. When sea level rise is removed, an Unnamed Hurricane (1903) and Hurricane Elena (1985) both produced water levels 10 feet above the annual mean sea level. Michael's storm surge will be comparable, or possibly exceed these levels, depending on the track.

Apalachee Bay, where NHC is predicting the highest storm surge from Michael—up to 12 feet—generates storm surge very efficiently because of its concave shape and shallow bathymetry. East-facing shores along Apalachee Bay in places like Apalachicola and Carribelle are generally more vulnerable than west-facing shores closer to where Michael is expected to make landfall, like Mexico Beach, because east-facing shores observe prolonged onshore winds as the hurricane approaches from the south.

West-facing coastlines, however, observe a prolonged offshore wind, followed by an onshore wind that suddenly strikes after the center passes. The rapid change of wind direction does not enable storm surge to build up as efficiently. This explains why east-facing Shell Beach, in eastern Louisiana near New Orleans, observed a higher storm surge (7.51’) than Morgan City (Amerada Pass) in central Louisiana (7.06’), from Texas-landfalling Hurricane Ike. Morgan City was approximately 85 miles closer to Ike's landfall than Shell Beach, but the west-facing shore limited Ike's storm surge potential in that small area.

What does 12 FEET of storm surge look like? We show you what the potential storm surge will be along Florida's Big Bend as #Hurricane #Michael approaches and makes landfall Wednesday. Our LIVE 24/7 team coverage continues. #IMR #ImmersiveMixedReality pic.twitter.com/nzNEZ1M9Oz

— The Weather Channel (@weatherchannel) October 9, 2018

Integrated Kinetic Energy: a better measure of storm surge potential

The Saffir-Simpson wind scale is an imperfect ranking of a hurricane’s storm surge threat, since it does not take into account the size of the storm and over how large an area the storm’s strong winds are blowing. As 11 am EDT, Michael was an average-sized hurricane, with tropical storm-force winds that extended out up to 185 miles from the center, and hurricane-force winds that extended out 35 miles from the center. If we sum up the total energy of the wind field present at that point, we come with an Integrated Kinetic Energy (IKE) of 40 Terrajoules, according to RMS Hwind. At that level of wind energy, Michael would be able to generate a storm surge characteristic of a typical of a Category 3 storm, even though it was still a Category 2 storm when the calculation was made. Michael's IKE values are very likely to increase from tonight into Wednesday.

For comparison, here are the peak IKE values of some historic storms at landfall:

Sandy, 2012: 330

Irma, 2017: 118

Ike, 2008: 118

Katrina, 2005: 116

Rita, 2005: 97

Maria, 2017: 78

Frances, 2004: 70

Matthew, 2016: 45

Harvey, 2017: 27

Andrew, 1992: 17

Charley, 2004: 10

|

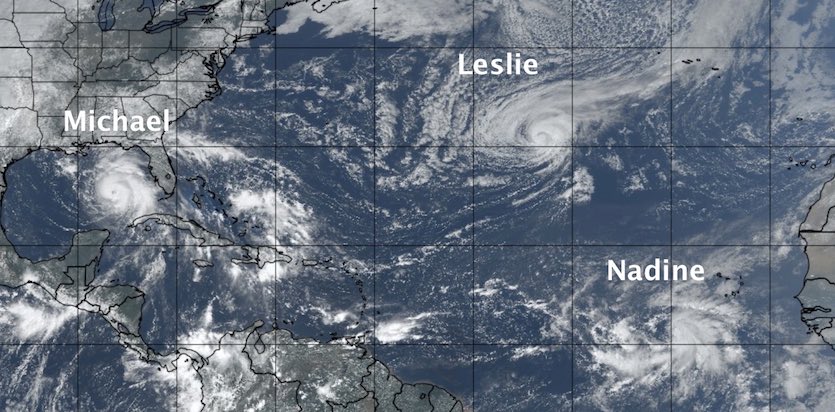

| Figure 3. Visible satellite image showing the Atlantic’s three named storms at 1620Z (12:20 pm EDT) Tuesday, October 9, 2018. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

Also in the Atlantic: Leslie and Nadine

You’d think it was August or September instead of mid-October, judging from the three named storms featured on today’s Atlantic hurricane tracking map. The veteran of the group is Tropical Storm Leslie, which has survived in the central North Atlantic since being named as a subtropical storm way back on September 23. Now moving east-southeast toward warmer waters, Leslie may become a hurricane again on Thursday. Models remain in big disagreement on whether Leslie will race eastward with a midlatitude storm system toward Europe this weekend, or get left behind and wander back westward, perhaps becoming one of the longest-lived named storms in Atlantic history.

Meanwhile, far out in the eastern Atlantic, Tropical Storm Nadine formed early Tuesday—the latest storm on record to develop so far east in the Atlantic tropics. Nadine should cause little trouble: it will soon encounter cooler waters and increased wind shear, along with steering currents that will keep it away from the Caribbean and U.S. East Coast.

It’s quite a feat to have three simultaneous named storms in the Atlantic during October. As pointed out by Dr. Philip Klotzbach (Colorado State University), the last time this happened so late in the year was back in 1950—which happens to be the very first year that tropical storms were routinely named by the National Hurricane Center. On October 18, 1950, we had Hurricane King, making landfall near Miami as a destructive Category 3 storm; Tropical Storm Twelve, spinning southeast of the Azores much like Nadine; and Hurricane Love, which developed quickly in the western Gulf.

Related post from Monday:

Historical Analogues for Hurricane Michael: Hermine, Dennis, Ivan, Opal, and Kate

Bob Henson co-wrote this post.