| Above: The strongest Atlantic hurricane of 2018, Hurricane Michael, as seen by GOES-16 at landfall in the Florida Panhandle on October 10, 2018. At the time, Michael was at peak strength, a Category 4 storm with 155 mph winds. Michael was the third most intense hurricane to make landfall in the contiguous U.S. based on central pressure, and the fourth most intense based on wind speed. Image credit: NOAA. |

A slightly below-average Atlantic hurricane season is likely in 2019, said the hurricane forecasting team from Colorado State University (CSU) in their latest seasonal forecast issued April 4. Led by Dr. Phil Klotzbach, with coauthors Dr. Michael Bell and Jhordanne Jones, the CSU team called for an Atlantic hurricane season with 13 named storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 intense hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 80. The long-term averages for the period 1981 - 2010 were 12 named storms, 6.5 hurricanes, 2 intense hurricanes, and an ACE of 92. The CSU outlook also predicted the odds of a major hurricane hitting the U.S. were about 48% (the long-term average is 52%). They gave a 28% chance for a major hurricane to hit the East Coast or Florida Peninsula (the long-term average is 31%), and a 28% chance for the Gulf Coast (the long-term average is 30%). The Caribbean was forecast to have a 39% chance of seeing at least one major hurricane (the long-term average is 42%).

“We have a lot of warmth in the subtropical Atlantic,” said Klotzbach in a livestreamed presentation Thursday from the National Tropical Weather Conference. As a result, Klotzbach said, he expects a relatively large number of weaker storms with subtropical elements, much like 2018, which set the Atlantic record for the largest number of storms (seven) that were subtropical during at least one point in their lives. This is one reason why CSU is predicting a near-average number of named storms but a lower-than-average number of hurricanes and ACE.

The CSU forecast has previously used only statistical techniques to make their forecasts. But this year, they collaborated with the Barcelona Supercomputing Center to use output from the ECMWF (European) model to augment the statistical technique. They used the European long-range ocean/atmosphere model to predict July 2019 conditions, which were then put into the statistical model. The warm sea-surface temperatures projected by statistical-dynamical models for hurricane season prompted Klotzbach and colleagues to bump up the number of named storms from the number predicted by the CSU statistical technique.

|

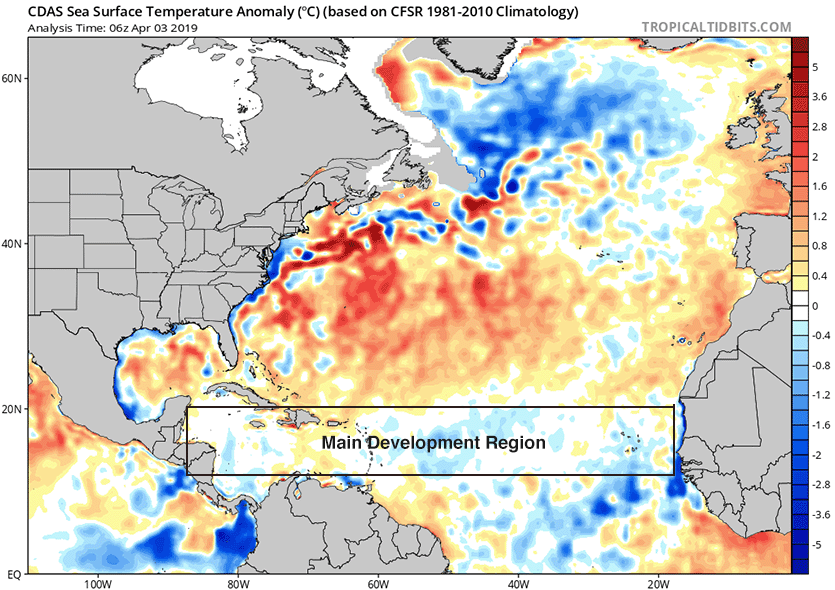

| Figure 1. Departure of sea surface temperature (SST) from average for April 3, 2019. SSTs in the hurricane Main Development Region (MDR) between Africa and Central America were near-average to slightly below-average. Virtually all African tropical waves originate in the MDR, and these tropical waves account for 85% of all Atlantic major hurricanes and 60% of all named storms. When SSTs in the MDR are much above average during hurricane season, a very active season typically results (if there is no El Niño event present). Conversely, when MDR SSTs are cooler than average, a below-average Atlantic hurricane season is more likely. Image credit: tropicaltidbits.com. |

Analogue years

Five years with similar pre-season February and March atmospheric and oceanic conditions were selected as “analogue” years that the 2019 hurricane season may resemble. These years were characterized by weak to moderate El Niño conditions during August-October, and near-average sea surface temperature (SST) in the tropical Atlantic:

1969 (18 named storms, 12 hurricanes, and 5 intense hurricanes)

1987 (7 named storms, 3 hurricanes, and 1 intense hurricane)

1991 (8 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 intense hurricane)

2002 (9 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 intense hurricanes)

2009 (9 named storms, 3 hurricanes, and 2 intense hurricanes)

The average activity for these years was 13 named storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 80—not far from the long-term average. The most notable storms during these years were Hurricane Camille of 1969, which made landfall as a Category 5 storm in Mississippi; Hurricane Emily of 1987, which made landfall in the Dominican Republic as a Category 3 storm; Hurricane Bob of 1991, which made landfall as a Category 2 storm in New England; and Hurricane Lili of 2002, which made landfall as a Category 1 storm in Louisiana.

|

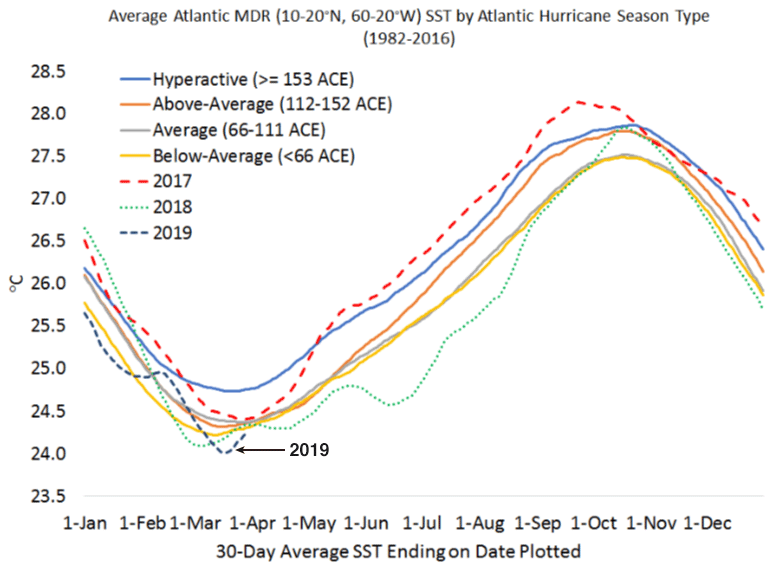

| Figure 2. Departure of SST in the tropical Atlantic Main Development Region (10 - 20°N, 60 - 20°W) plotted for the average of various Atlantic hurricane season types from 1982-2016. Also plotted are 30-day running averages of SSTs for 2017, 2018 and 2019. So far, 2019 is tracking in line with below-average Atlantic hurricane seasons in previous years. However, there is very little spread between below-average, average and above-average hurricane seasons at this time of year. Image credit: Colorado State University (CSU), from their latest seasonal forecast issued April 4. |

A weak El Niño and near-average tropical Atlantic SSTs expected

The CSU team cited two main reasons why this may be a slightly below-average hurricane season:

1) The current weak El Niño event in the Eastern Pacific appears likely to continue and perhaps strengthen during the summer/fall. If El Niño conditions are present this fall, this would tend to favor a slower-than-usual Atlantic hurricane season due to an increase in the upper-level winds over the tropical Atlantic that can tear storms apart (higher vertical wind shear).

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were about 0.7°C above average during the past month in the so-called Niño 3.4 region (5°S - 5°N, 120°W - 170°W), where SSTs must be at least 0.5°C above average for five consecutive months (each month being a 3-month average) for a weak El Niño event to be declared (and atmospheric conditions must also be consistent with El Niño). In their latest March 14 monthly advisory, NOAA's Climate Prediction Center (CPC) predicted that the current weak El Niño event has a 60% chance of continuing into the summer. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology, which uses a more stringent threshold than NOAA for defining El Niño, does not recognize that an El Niño event is underway. In the April 2 installment of its biweekly report, the Bureau said that the atmosphere has yet to “show a consistent El Niño-like response”, but maintained their El Niño alert, with a 70% chance of an El Niño developing later this year. The Bureau requirement for an El Niño is for sea-surface temperatures in the Niño3.4 region of the tropical Pacific to be at least 0.8°C above average, vs. the NOAA benchmark of 0.5°C above average.

Among the latest predictions from a large number of statistical and dynamical El Niño models for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season in August-October, about 1/3 of the models called for neutral conditions, about 2/3 called for El Niño conditions, and none predicted La Niña conditions.

2) The tropical Atlantic is slightly cooler than normal, while the subtropical Atlantic is quite warm, and the far North Atlantic is anomalously cool. The anomalously cool sea surface temperatures in the far North Atlantic suggest that the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) is in its negative phase. A positive AMO is typically linked with above-average Atlantic hurricane activity; a negative AMO is typically associated with below-average activity.

As always, the CSU team included this standard disclaimer:

"Coastal residents are reminded that it only takes one hurricane making landfall to make it an active season for them. They should prepare the same for every season, regardless of how much activity is predicted."

|

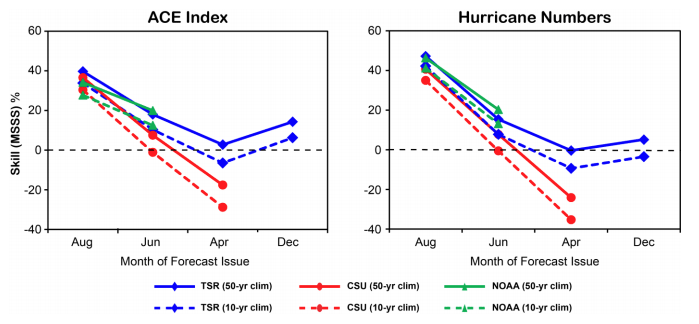

| Figure 3. Comparison of the percent improvement in mean square error over climatology for seasonal hurricane forecasts for the Atlantic from NOAA, CSU and Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) from 2003-2018, using the Mean Square Skill Score (MSSS). Values less than zero indicate that pure climatology does a better job than the forecast. The figure shows the results using two different climatologies: a fixed 50-year (1951 - 2000) climatology, and a 10-year 2009 - 2018 climatology. Skill for forecasts issued in December and April is close to zero, is modest for June forecasts, and is moderate-to-good for August forecasts. Using this methodology, TSR has had the best seasonal forecasts. Image credit: Tropical Storm Risk, Inc. (TSR). |

April hurricane season forecasts have little or no skill

On average, April forecasts of hurricane season activity have had no skill (Figure 3), since they must deal with the so-called "spring predictability barrier." April is the time of year when the El Niño/La Niña phenomenon commonly undergoes a rapid change from one state to another, making it difficult to predict whether we will have El Niño, La Niña, or neutral conditions in place for the coming hurricane season. Last year’s CSU April forecast called for a slightly above-average Atlantic hurricane season for 2018, with 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 3 intense hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 130. This forecast ended up being successful, as the season actually had 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 129.

The next CSU forecast, due on June 4, is worth paying more attention to. Their late May/early June forecasts have shown considerable skill over the years. NOAA issues its first seasonal hurricane forecast for 2019 in late May, with an update in August.

TSR predicts a slightly below-average Atlantic hurricane season

The April 5 forecast for the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season made by British private forecasting firm Tropical Storm Risk, Inc. (TSR) calls for a slightly below-average Atlantic hurricane season--about 20% below the long-term (1950-2018) norm and 30% below the recent 2009-2018 ten-year norm. TSR is predicting 12 named storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 intense hurricanes and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 81 for the period May through December. The long-term averages for the past 69 years are 11 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 intense hurricanes and an ACE of 104. TSR rates their skill level as low for these April forecasts--just 2 - 7% higher than a "no-skill" forecast made using climatology. TSR predicts a 29% chance that U.S. landfalling ACE index will be above average, a 24% chance it will be near average, and a 47% chance it will be below average. They project that two named storms and one hurricane will hit the U.S. The averages from the 1950-2018 climatology are three named storms and one hurricane. They rate their skill at making these April forecasts for U.S. landfalls at 0% - 3% higher than a "no-skill" forecast made using climatology. In the Lesser Antilles Islands of the Caribbean, TSR projects one tropical storm and no hurricanes. Climatology is one tropical storm and less than 0.5 hurricanes.

TSR’s main predictor for their statistical model of Atlantic hurricane activity is the forecast July - September trade wind speed over the Caribbean and tropical North Atlantic. Their model is calling for trade winds 0.83 m/s faster than average, due to the anticipated weak-to-moderate El Niño conditions during the summer/autumn of 2019 and slightly cooler than average SSTs. Stronger than normal trade winds during July-August-September are associated with less spin and increased vertical wind shear over the hurricane main development region, factors that reduce hurricane frequency and intensity. The next TSR forecast will be issued on May 30.

Bob Henson contributed to this post.