| Above: Sea level was higher than average (red/orange areas) in early October across most of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, a sign of unusually warm water in line with a developing El Niño event. Data are from a radar altimeter aboard the OSTM/Jason-2 satellite that collects sea surface height data from across the world’s oceans. Image credit: JPL/Caltech. |

With some help from a weak El Niño event, atmospheric factors are aligning for a mostly mild winter across the United States in 2018-19, according to the seasonal outlook issued by NOAA on Thursday. The biggest area of uncertainty is the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic. In that region, NOAA is calling for equal odds of warmer- or cooler-than-average conditions (effectively a coin toss). Other seasonal forecast groups are in stark disagreement on what's in store for the eastern U.S.

|

| Figure 1. Outlooks for temperature (left) and precipitation (right) issued by NOAA for the upcoming meteorological winter, or the period from December 2018 through February 2019. Where “equal chances” is shown, the odds are roughly 33% each for below-, near-, or above-average conditions. Image credit: NOAA/NWS/CPC. |

El Niño events typically peak during northern winter, when they have the most influence on conditions across North America. That’s likely going to be the case for the event now developing. The latest probabilistic forecast from CPC/IRI (the NOAA/NWS Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society) shows the odds of El Niño conditions peaking at around 70 – 75% in the November-to-January period, then slowly waning through the winter and dropping below 50% by spring.

A weak El Niño event has a much less reliable influence on U.S. winter weather than does a strong El Niño event, such as 1982-83, 1997-98, and 2015-16. This difference is brought out in a set of NOAA maps compiled by Jan Null (Golden Gate Weather Services). Null shows the year-by-year temperature and precipitation patterns that occurred with El Niño and La Niña events of various strengths over the past 68 years. Strong El Niño conditions tend to favor relative mildness over the northern U.S. and Canada and relatively cool winters along the southern tier of U.S. states. This signal is diminished during a weak El Niño event, when the outcomes vary more widely from event to event. Likewise, the tendency for a strong El Niño to favor wet conditions over the U.S. West Coast and the Southeast is muted during a weaker El Niño.

With all this in mind, NOAA’s winter outlook for temperature (Figure 1, left) is dominated by the tendency toward warmer winters in recent years, right in line with what we’d expect from human-produced climate change. The precipitation outlook has an El Niño tinge: wet toward the south, drier to the north.

Texas is off to a head start in the moisture department, as early autumn has produced widespread heavy rain and intense flooding in some areas. Floodgates were being opened on multiple dams in the Colorado River system northwest of Austin on Thursday, two days after the Llano River (which feeds into the system) experienced its highest crest since 1935 (see weather.com feature). Dallas-Fort Worth has already smashed its precipitation record for any autumn (September – November) by more than 2”, with a total of 23.89” from Sept. 1 to Oct. 17—and we’re only little more than halfway through the season. The six-week total ending Oct. 17 (23.65”) is tied with a six-week span ending on May 26, 1957, for the wettest such period in DFW’s entire weather record, which goes back to 1898. (Thanks to Alan Gerard, National Severe Storms Laboratory, for this statistic.)

.@JimSpencerKXAN Rain, rain GO away! There's a street at the end of my driveway but it's under water. Surreal watching the lake creep up. 702.2' and counting. #laketravis #lagovista #2018flood pic.twitter.com/PvyE3xRVbc

— Michele Seib (@msfunsun) October 18, 2018

Two big question marks

El Niño’s impact on U.S. winter weather hinges not only on how strong an El Niño it is, but also on where the strongest Pacific warming is focused. A “classic” El Niño features a tongue of warmer-than-average water extending west from South America along and near the equator. Sometimes the warming is more prominent toward the central Pacific, which leads to what’s been dubbed an El Niño Modoki event.

Since the ocean warming during El Niño Modoki is positioned farther away from North America, the U.S. impacts can vary as well. There appears to be a greater tendency for colder-than-average conditions to develop in the eastern U.S. during a Modoki event. Several global models, including the European (ECMWF) model and several members of the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), are suggesting that the expected El Niño event in 2018-19 may have a Modoki flavor, as they are calling for the El Niño warming to be at least as strong in the central Pacific as in the eastern Pacific.

Another uncertainty for the eastern U.S. is the state of the Arctic Oscillation (AO) and the closely related North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). A positive AO/NAO corresponds to a tight polar vortex focused at higher latitudes, whereas a negative AO/NAO is related to a weaker vortex, one that can more easily allow polar cold to spill into midlatitudes. The AO and NAO have trended consistently positive over the last few months, in line with record warmth across much of the Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes.

NOAA’s seasonal forecast group does not attempt to predict the AO or NAO months in advance. However, NOAA’s Michael Halpert said in a Thursday press conference that the “equal chances” area for temperature allows for the possibility of a negative AO/NAO.

Two other forecast groups have divergent takes on what might happen in the eastern/southeastern U.S. this winter:

—The Weather Company’s most recent seasonal outlook calls for an increasing chance of colder-than-average conditions setting into the eastern U.S. during the latter part of winter, especially in February (see Figure 1 below). This is based in part on signals from the emerging El Niño, including its potential to be a Modoki event, and partly on the possibility of a weaker-than-usual polar vortex.

|

| Figure 1. Month-by-month outlooks for U.S. temperature from November 2018 through February 2019, produced in early October by the forecasting group at The Weather Company. |

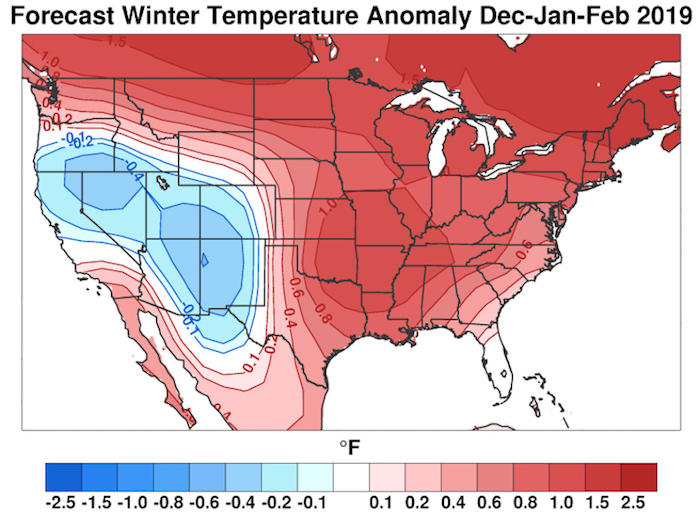

—The latest outlook from a winter forecasting project funded by the National Science Foundation and led by Judah Cohen (Atmospheric and Environmental Research), issued on Thursday, calls for warmer-than-average conditions from January to March over all of the U.S. and southern Canada except for the Southwest U.S. (see Figure 2 below). In an AER blog post on Monday, Cohen noted that snowfall during October has been running below average over Europe and Asia, including Siberia.

“Below normal snow cover extent favors a weakened Siberian high, mild temperatures across northern Eurasia and a stengthened polar vortex/positive AO this upcoming winter followed by mild temperatures across the continents of the [Northern Hemisphere],” said Cohen.

|

| Figure 2. Departures from the average winter surface temperature (degrees F) for December 2018 – February 2019, as predicted by a seasonal forecasting project led by Judah Cohen (Atmospheric and Environmental Research). The project’s model is forecasting below-normal temperatures for the southwestern United States, the Central Rockies, northern California and southern Oregon, with above-normal temperatures for the remainder of the U.S., including the northern and eastern U.S. Image credit: AER/NSF. |

The evergreen caveat for seasonal outlooks

As always, we have to approach seasonal outlooks with a subseasonal grain of salt. A winter that’s otherwise mild may be remembered as a brutal one if it includes a one- or two-week period of vicious cold and/or heavy snow. It’s the short-term departures that often become the hallmark of a given winter. Thus, we should always be prepared for a given few days in winter to depart greatly from the seasonal tendencies shown in the outlooks above.